Ever heard of butterfly farming as a profession?

Neither had I–until four years ago when I dug into the craft and science of raising butterflies at home. Rearing butterflies in my kitchen was such fun, I thought I wanted to be a professional butterfly farmer. I quit my corporate marketing position in late 2011, applied for USDA permits to ship butterflies to the 48 contiguous states and cultivated my membership in the International Butterfly Breeders’ Association (IBBA).

Yes, the IBBA. The trade association of more than 100 butterfly breeders serves as a great place to learn about rearing butterflies from people who do it professionally.

Each year the IBBA stages a conference. It’s geared to professionals but is open to others. I joined the organization and attended my first butterfly convention in Las Vegas as a curious observer in 2009. The 2013 Convention takes place in my hometown of San Antonio this November in conjunction with another butterfly breeders group, the spin-off Association for Butterflies. The combined event will commemorate the 15th anniversary of the founding of the butterfly breeding industry. Feel free to join us.

Apart from these annual gatherings, the far-flung, ferociously independent butterfly farmers rarely see each other in person. Most were drawn to the profession for the love of the species rather than monetizing their passion. They communicate constantly through an active, members-only listserv that functions as a commodities exchange:

“Need six dozen Monarch pupae for funeral this weekend. Please contact me offline.”

“Painted lady larvae available. Email me directly.”

But this hyperactive email list also works as an insiders’ guide to detailed information on the persnickety process of producing butterflies on demand. From best practices for propagating host plants to how to deal with common caterpillar maladies, I have learned much from this group.

One of the most generous resources on the IBBA list is Edith Smith of Shady Oak Butterfly Farm in Brooker, Florida. Smith grew up on a peanut farm in the Sunshine State, 15 miles north of Ocala, “in the middle of nowhere,” as her father used to say. She found her way to butterfly farming in 1999. The farm evolved, as many butterfly related activities tend to do, from a gardening passion–in this case, an herb farm she and her husband started. She and her retired pharmacist husband Stephen Smith now raise several thousand pupae and/or butterflies a week.

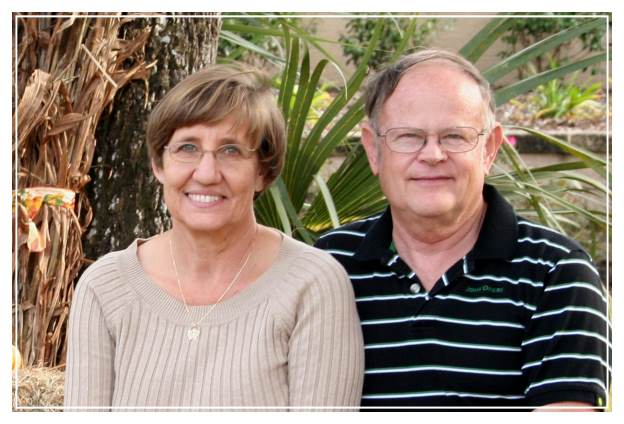

Edith Smith and her husband Stephen, who’s career as a pharmacist and science background greatly assisted the development of their Shady Oak Butterfly Farm. –Courtesy photo

In the beginning, the Smiths sold butterflies, caterpillars, and chrysalises to a single broker. “We raised about 12 species at that time but had not yet tried Monarch or Painted Lady butterflies,” said Edith via email.

LIke many butterfly lovers, Smith was taken aback by the general population’s obsession with Monarchs. Many professional and novice lepidopterists don’t understand the focus on Monarchs when so many other amazing butterfly species abound and merit attention. Monarchs get all the press, and in the butterfly breeding business, the dramatic migrant is a money crop–constituting the bulk of sales in the multi-million dollar industry.

“Because we sold only to one broker who resold to exhibits, we didn’t realize that Monarchs and Painted Ladies were the two main sources of income for most butterfly farmers,” said Edith. The couple quickly changed their strategy and added the two bread-and-butter species to their line-up.

Generally, Monarchs are the preferred species for releases at weddings, funerals and celebrations, while Painted Ladies are often used en masse in science classrooms and home school situations as part of science curricula.

The Smiths were selling 500 – 1,000 pupae per week by the end of their first year. They increased their species count from 12 to 20. Back then a high volume broker could buy a chrysalis for $1. Today a chrysalis can cost $3 – $10, depending on the species and who’s buying it.

These days, Shady Oak, one of the largest farms in the industry, produces up to 6,000 pupae per week and grosses about $300,000 per year. “But costs are high,” said Smith, noting the operation includes a staff of six family members and an equal number of greenhouses to raise host plants.

Four laboratories, a shipping/packing area and various screened 12’x12’x16′ butterfly “apartments” allow for mating and hatching of various species on the Shady Oak grounds. The Farm ships to myriad flyhouses, zoos and natural history exhibits and supplies livestock to hundreds of weddings, funerals, events and schools for celebration, commemoration and education each year.

Smith led a tour of one of the Farm’s “rearing rooms” for IBBA members at the 2011 convention in Gainesville, Florida. –Photo by Monika Maeckle

Shady Oak once opened to the public for tours and field trips, but now the farm offers visits by appointment only. Smith also welcomes fellow butterfly farmers and like several breeders, hosts educational seminars and an internship program aimed at teaching best practices. “Our first seminar was in 2003 with 64 people,” she said. These days, for health reasons, Smith prefers one-on-one week-long internships. “We have met the most fantastic people!” she said, including visitors from 12 countries.

Shady Oak has mastered breeding the uncommon Blue Buckeye. Photo via Edith Smith, Shady Oak Butterfly Farm

The Smiths are especially proud of their Blue Buckeyes, their specially bred blue-winged Common Buckeye. Just like other types of farmers and ranchers, a butterfly breeder can breed for desirable traits. In this case, the Smiths focused on the beautiful iridescent blue sometimes observed on the wings of the Common Buckeye, Junoeia coenia.

Whenever the Smiths noticed blue in the background of recently emerged Buckeye wings, they isolated the creature’s eggs for breeding. Over time, each generation produced more pronounced iridescent blue in the background of the Buckeye’s wings. Eventually, “Buckeye butterflies emerged with the entire background of their wings a remarkable metallic blue,” notes Smith on her educational website, Butterfly Fun Facts. See the video below for a glimpse at this amazing creature.

Smith is always quick to share advice and rearing tips on her Facebook page, her websites, on the proprietary IBBA listserv, and through the Association for Butterflies. Isn’t she concerned about disclosing trade secrets?

“The more we all share the better off we all are!” she said via email. That attitude led her to help found the Association for Butterflies along with Jodi Hopper and Mona Miller, an educational-oriented organization for professional breeders that helps to promote best practices for butterfly lovers of all stripes.

Smith believes the butterfly breeding industry must share and improve its practices to continue growing. “There’s more demands for butterflies than we farmers can supply,” she said. “Teaching others to raise butterflies means that when supply is low, we will be more likely to find someone to dropship to our customers.”

Smith also credits her farm’s proximity to the University of Florida and the McGuire Center for Biodiversity and Lepidoptera in nearby Gainesville. “The people there are very generous with their time and knowledge. They have helped us more than we can say.”

At age 58, Smith is turning her attention to writing books about butterfly rearing and implementing a two-year succession plan. Her eldest daughter, Charlotte, has become part owner of the farm, which the couple incorporated last year. Daughter-in-law Michelle manages the office, takes orders and often packs and ships 40-50 orders of live butterflies, pupae, caterpillars, eggs and/or butterfly gear a day. Shady Oak also employs several other staff members that keep the place running smoothly.

Smith and her husband Stephen plan to attend the IBBA/ABF Joint Conference in San Antonio this November.

If you want to meet Edith and learn about raising butterflies from her and others who do it for a living, check out the convention page for further details.

As for me, I will remain a NONprofessional butterfly farmer/rancher for the foreseeable future. After completing my first paying gig as the Texas Butterfly Ranch, which was to supply 500 live butterflies to the University of Texas at Austin’s First Annual Insecta Fiesta in April of 2012, I realized immediately I’m a better marketer than rancher. Special thanks to another generous farmer, Connie Hodson of Flutterby Gardens, for helping me fill the order.

Lesson learned: it’s much easier and less stressful to produce blogposts and marketing plans on deadline than to deliver hundreds of live butterflies by a predetermined date. For now, I’m sticking to my profession and raising butterflies for fun.

More posts like this:

- Founder of the Monarch Roosting Spot Lives a Quiet Life in Austin, Texas

- How to Raise Monarch Butterflies at Home

- Part II: More Tips on Raising Monarch Caterpillars and Butterflies at Home

- FOS Monarch Lays Eggs in San Antonio Urban Garden

- Tropical Milkweed: To Plant it or Not is No Simple Question

- Oh Those Crazy Chrysalises: Caterpillars in Surprising Places

- Butterfly FAQ: Is it OK to Move a Chrysalis? Yes, and here’s how to do it

- Should You Bring in a Late Season Caterpillar into Your Home?

Like what you’re reading? Don’t miss a single post from the Texas Butterfly Ranch. Sign up for email delivery, like us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter, @monikam.

I don not intend to raise butterflies, just want to supply them with nectar and food for caterpillars. I have a dark red milkweed and have one caterpillar on them. Should I just leave it be and trust that it will survive or is there something I should do to make sure it lives?

HI Dorlis,

If you want to “make sure” it lives, you should bring it inside where you can keep an eye on it. It will eat milkweed leaves that you can break off the plant or stalks with leaves that you can put in a vase. When it’s ready to form a chrysalis, it might wander away from the plant, but it could also form the pupae right there. It’s fun to watch the process and later the hatching. Check out the links at the bottom of this post on raising butterflies at home. All the details are there. If you leave it outside, you will never be sure if it lived, but then, that’s Nature’s way. Good luck! –MM

Are the Blue Buck eye butterflies ever seen in the wild or are these only produced through breeders?

Terrific article! Thank you.

I so enjoy reading both postings to Facebook: yours and Edith’s.

Keep spreading the joys of gardening for and enjoying wildlife …. butterflies – “free to fly, fly away, high away” …

Today my Silvery Checkerspots began emerging en masse!

so so lovely.

Take care, Kat

What an excellent article about Edith Smith, one of my very favorite people. She is the person who has inspired me to start my own butterfly farm business and has encouraged me all along the way. And yes, it is hard work keeping all those hungry caterpillars fed!

Your article covered EVERYTHING. TY so much. Was fortunate enough to visit Shady Oak Butterfly Farm in person last July on a Saturday. Edith gave me two hours of her time showing me everything and answered all my questions! In the buckeye apartment there was a blue buckeye with some purple in its wings. It was indeed a fantastic day and Edith and Stephen are remarkable people.

Breeding butterflies for color… Just like deer farming for antler size. Bad plan. Might end up with the Irish Setters of the butterfly world. Hubris to think we can make better creatures.

I am trying to find a way to get 2 dozen butterflies to release 23 butterflies for my daughters birthday. She went to Heaven one year ago this past December and I still grieve and love her more every day. She would’ve been 23 this July 24. When I think of her I cannot help but think of butterflies, beautiful, free. No more pain or sadness. Thank God she is safe now.

Will you please contact me via email regarding this heartbroken matter?

Very good info !! Thanks !! I am planning on starting to breed Monarchs and Painted Ladies.