It’s mid November and Monarch butterflies continue to visit my San Antonio pollinator garden. Lighting on Cowpen daisy, Duranta, Gregg’s Purple mist flower and several kinds of milkweed, the butterflies have extended their visits long past their usual late October stay.

Nov. 12,. 2015: Monarchs still visiting my San Antonio garden, this one on Duranta. Photo by Monika Maeckle

That’s not to say we don’t sometimes have Monarchs visiting this late in the season. We do. In fact, we’ve had many questions from folks up north about what to do with late hatching Monarchs when the weather turns cold. A previous post addresses that. But I don’t ever recall having this many Monarch butterflies this late, and so consistently.

“Yesterday, I saw hundreds of Monarchs in Austin,” wrote John Barr of Native Cottage Gardens in Austin on November 1 in a post to the DPLEX list, the old school email listserv that reaches about 800 butterfly enthusiasts. ” I saw more Monarchs in 30 minutes than I’ve seen all year. Bright, fresh, long-winged migrating Monarchs of both sexes.”

Monarchs were even spotted recently as far north as Lake Erie, according to Darlene Burgess of Point Pelee, Leamington, Ontario. “There are still Monarchs being seen in Ontario on Lake Erie’s north shore. This week’s warm temps up to 70° should get them south across the lake,” she wrote November 2 on the DPLEX list.

Late season blooms continue to attract Monarchs and other pollinators to my urban San Antonio garden. Photo by Monika Maeckle

Our friends at the Natural Gardener in Austin, which stocks several kinds of native milkweeds, said they’ve had a steady stream of Monarchs visiting as well. “They LOVE the Duranta,” said Curt Alston, buyer for the organic nursery. Alston added that he has plenty of caterpillars and chyrsalises on the native milkweeds, and that adult Monarchs are still breezing through the aisles.

What gives?

Climate change. September 2015 was the hottest month in recorded history. October ranked the fourth hottest. Overall, 2015 is likely to be the hottest year ever, says the New York Times.

Warmer temps mean extended growing seasons. Plants that typically wouldn’t thrive when fall arrives will continue to grow and bloom, creating more nectar for migrating Monarchs, and in some cases, host plant.

Increased temperatures also mean that Monarch butterflies will likely break their diapause–that is, their asexual state of resisting reproductive activities so as to conserve energy for migrating to Mexico. Once Monarchs reproduce, they don’t migrate.

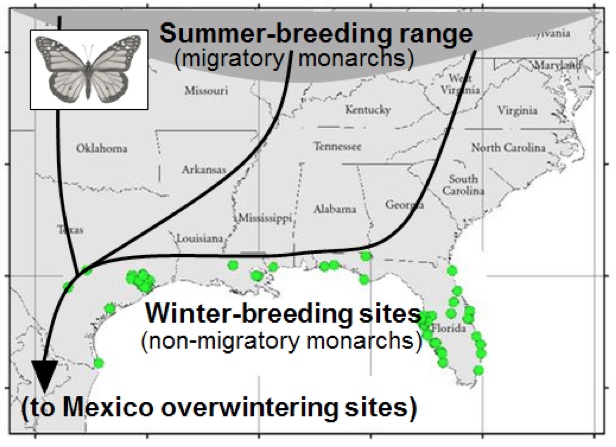

Breaking diapause increases the chances of more year-round Monarch butterfly colonies. Map via Monarch Joint Venture

“We’ve got to get used to the late Octobers and Novembers as part of our future,” said Dr. Chip Taylor, founder of Monarch Watch, the citizen scientist tagging program operated by the University of Kansas at Lawrence.

Taylor predicts that a larger proportion of these late Monarchs will be unable to maintain their diapause and become reproductive. “Their hormones work on the basis of temperature. It’s very delicate and complicated,” he said via phone. “The warmer it is, the more likely it is the Monarch will not be able to maintain a diapause.”

Hmm. So where does that leave butterfly gardeners? Should we encourage egg laying with native or clean Tropical milkweed, or just let all those good eggs go to waste?

Tropical milkweed: cut it to the ground in the fall to prevent build-up of OE spores. Photo by Monika Maeckle

Research from scientists like doctoral student Dara Satterfield and Dr. Sonia Altizer out of the University of Georgia indicates that the year-round availability of Tropical milkweed makes Monarchs more prone to contracting Ophryocystis elektroscirrha, a debilitating protozoan parasite commonly known as OE in Monarch butterfly circles. Since OE spores transfer via physical contact between creatures or the plants on which they rest or eat, having year-round milkweed which is visited repeatedly by Monarchs and other butterflies creates a hotbed of these nasty spores and spreads the disease.

Satterfield, et al, suggest hard-to-find native milkweeds should be planted rather than the technically nonnative Tropical milkweed, which is widely available and easy to grow. Best practice dictates close management of Tropical milkweed. Cut it to the ground late in the season so OE spores don’t build up and infect migrating Monarchs.

But what about all the other plants that Monarchs frequent? In my yard, the native Swamp milkweed continues to thrive and various nectar sources have been repeatedly visited by Monarchs and other butterflies since April. As the Natural Gardener’s Curt Alston said above, Monarchs are loving the lush, purple bloom of Duranta that laces my fence perimeter. They also repeatedly visit my golden-yellow, late season Cowpen daisies.

Wouldn’t these plants also host the same debilitating OE spores so closely associated with late season Tropical milkweed after so many return visits from Monarchs? Should we cut those plants down as well, to avoid infecting visiting flyers?

Scientists, what say you?

- What to do with late season Monarchs

- MIghty Monarchs brave south winds, Hurricane Patricia, to arrive in Mexico

- Desperately Seeking Milkweed: Monarch Caterpillars Appetites Create Milkweed Emergency

- Butterfly Farmer Edith Smith Keeps it All in the Family at Shady Oak Butterfly Farm

- How to Raise Monarch Butterflies at Home

- Part II: More Tips on Raising Monarch Caterpillars and Butterflies at Home

- Tropical Milkweed: To Plant it or Not is No Simple Question

- Oh Those Crazy Chrysalises: Caterpillars in Surprising Places

- Butterfly FAQ: Is it OK to Move a Chrysalis? Yes, and here’s how to do it

- Should You Bring in a Late Season Caterpillar into Your Home?

Like what you’re reading? Don’t miss a single post from the Texas Butterfly Ranch. Sign up for email delivery, like us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter, @monikam.

Are the overwintering sites in the US recent or over many years? My sister in Katy near Houston has had Christmas caterpillars for a couple of years. The butterflies emerged, but the later iffy weather was tricky for release. Also, there have been earlier questions about places where tropical milkweed IS native. Do they have OE problems, too?

I am only 35 miles north of Mexico, in southern CA. Tropical is native in Mexico. So a political line dictates that Tropicals are not native to CA. And yes, we have a high incidence of O.e. spore infested butterflies. There are many reasons for this.

Just because Dara Satterfield and Dr. Sonia Altizer are interested in studying Oe does not mean that it represents a significant threat to Monarchs. The implication that Tropical Milkweeds vectors Oe any differently than any other milkweed is unfounded. What is the consensus among academics and citizen scientists is that we need a vastly greater number of milkweed available for Monarchs to host on. Tropical milkweed should be planted along with many other varieties if we wish to increase the number of Monarchs in out-years.

I wish I had that beautiful screened room, I would invite them in overnight and give them some heat and let them go next day. /what a beautiful place to raise caterpillers safe from predetors. Lots of room for flowers.

My problem is finding Tropical Milkweed for hatch-lings. Now that we’re mid-November, the greenhouses no longer carry it.

Tropical milkweed germinates really easily in a shallow pot with damp soil. You can use the seeds from the pods to make milkweed “cat food” and let them grow just a few inches tall and let the caterpillars cut them back. It’s also completely clean, since its from seed. Good luck! –MM

Monika that is a great suggestion. We start several multi-plant pots in the spring as food sinks for the Monarchs they always are eaten back at some point in time during the breeding season.

After two great seasons of monitoring the monarchs in our northern Virginia garden, we were really disappointed this 2015 summer to be totally “skipped” by our beautiful travelers.

We so appreciate the info you forward, and will hope for a return to the migration route NEXT summer/fall !

Monika,

“Cut it to the ground.” That’s clear enough. But the next question is, does the plant come back again next Spring? With no leaves and very little stem showing?

If the answer is no, then are you saying kill the plant? In which case, why not dig the poor thing up? (We are in S. California.)

Please enlighten. Thanks as always for your informative missives from the front lines,

Jim Miller

Just cut it to a few inches from the ground. It will come back in the spring. It also seeds profusely and new plants will germinate if you get seed pods. Good luck! –MM

Jim if you live in an area with frost this is not necessary because it will be winter killed. In frost free areas such as the Rio Grande Valley of Texas we cut back 1/2 of the plant in November to about 9″ from main stalk and when this starts to leaf out again we will then cut back the second half. This makes for a nice leafy plant in the spring for the Monarch migration. Hope you find this helpful.

It doesn’t need to be cut to such a short stump! Cut it to 4″, and then keep it rinsed. Your plant will come back the next year. If you can, use fine netting to cover those plants until you feel that the last of the butterflies have visited.

Remember that neighbors or people in your community may not follow this recommendations, and may be allowing the butterflies to reproduce. Which means you need to devise a way to keep your plants safe from more eggs.

Thank you for stating so clearly this important issue. Yes, as Dr. Taylor indicated, O.e. spores are on any plant that the butterflies may visit. The concern about tropical milkweed and O.e. spore build-up is a bit overstated. Yes, a gardener should be cutting back their tropical milkweed several times a year, if only to let the plant rest and regenerate. But most of us who have tropical milkweed plants don’t need to cut back our plants. The caterpillars do that for us! Several times a season, the tropical milkweed plants are eaten to the ground. Literally. I have been suggesting that gardeners take the time to clean up what is left of the tropical plant and put it aside and “rinse” the soil through repeatedly as the plant regenerates itself, and leafs out again. The spores can be on the soil as well as on the plant, and can be picked up by wandering caterpillars. But that native milkweed plant that continues to grow throughout most of the year could also be a “carrier”. Again, I recommend that a gardener make sure that those native milkweed plants must be maintained with the same diligence. When eaten back, clean up the remnants of the plant, put it aside to regenerate and rinse the soil. And yes, what about those nectar plants that are native but bloom almost all year? They too are hosts to O.e. spores. What do we do about them? Again, due diligence is required. Clean up spent blooms and rinse the plant and soil.

This past season, I used just plain water to rinse the eggs and leaves fed to them. All were O.e. spore FREE.

I left the next batch on the plants but collected the chrysalides. The butterflies from this batch were mixed~some had O.e. spores, some did not.

Then I tried rinsing the plants repeatedly (not an easy thing in the CA restricted water time). Rinse the leaves and soil, and rinse again. I also kept the nectar plants rinsed down. The butterflies that were raised on these plants, outside in hampers over the plants, were about 75% O.e. spore free.

My theory? Here in southern CA, we just don’t get enough rain to rinse the plants naturally in a good rain. So the gardener must devise ways to be water smart and rinse the plants for nature.

The project will continue this next year. I choose to shut down my garden by covering my milkweed plants to give them a rest. Not to mention the stroke that made raising the caterpillars a bit more difficult. By February, when I hope to see new plant growth, the project will begin again.

Thanks again for your article!

I heard about Cowpen Daisy some years ago, but have not been able to find seed anywhere.. Does anyone have some to share if I send a SASE? It would be greatly appreciated!! 🙂 Thanks!

Thanks to Monika, William and Nancee for the detailed answers! Very helpful.