They said it couldn’t be done. That a commercially raised Monarch butterfly couldn’t migrate. But Jenny Singleton of the Grapevine Butterfly Flutterby Festival and one commercially grown Monarch proved that a butterfly tagged and released in Texas can find its way 1,114 miles south to join its brothers and sisters in Mexico for the winter.

Monarch WGX139 was raised in a commercial butterfly farm, probably somewhere in Florida. On Wednesday, October 12, 2016, Connie Hodsdon of Flutterby Gardens in Bradenton shipped more than 500 Monarch butterflies to Grapevine, Texas. The community sits between Dallas and Ft. Worth, right on the IH35 “Monarch Highway.” Each fall during peak Monarch migration season, usually the second or third week in October, Grapevine celebrates its annual Butterfly Flutterby Festival with the release of hundreds of butterflies. This year, the Festival’s 20th, it will take place Saturday, October 14.

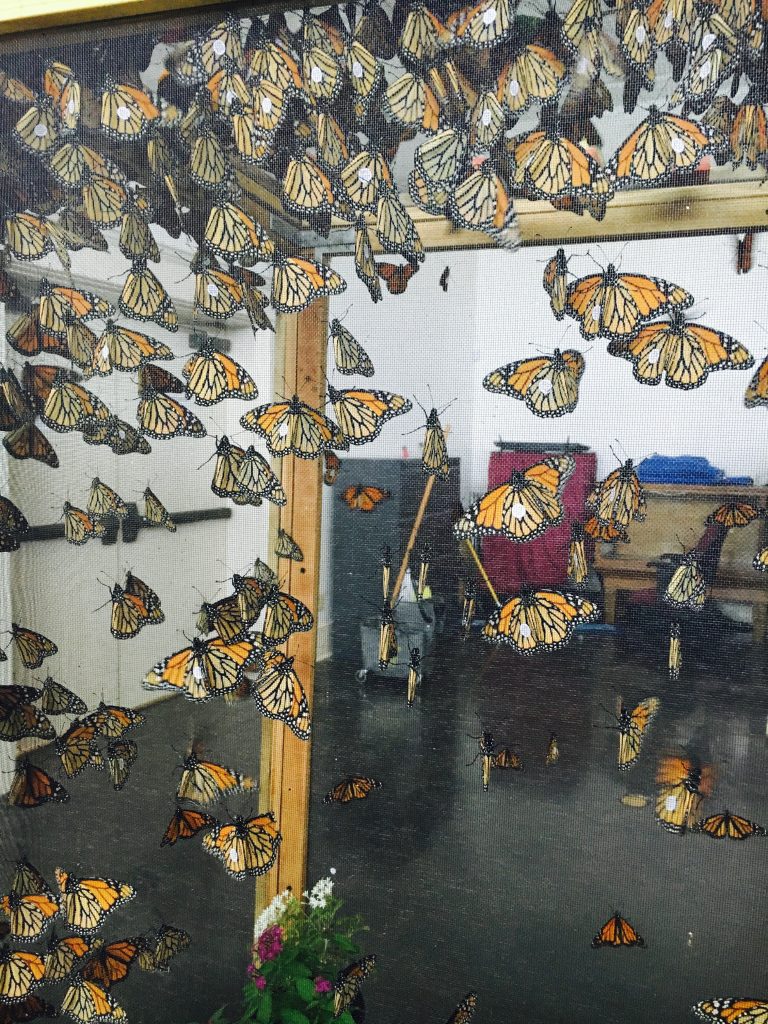

Bradenton’s box full of Monarchs, each packed in individual glycine envelopes and surrounded by protective styrofoam and ice packs, arrived for last year’s festivities on Thursday, October 13. Butterfly wranglers Jenny Singleton and other volunteers tagged the butterflies upon their arrival, then moved them to a large, open air cage where sliced oranges and watermelon awaited. Singleton and her crew regularly spritzed the butterflies with water throughout the day on Friday to keep them hydrated. Fresh fruit was replenished as needed while the butterflies awaited their Saturday debut.

Starting at 10 AM on Saturday, Festival-goers arrived for a costumed parade, butterfly crafts and exhibits, a “migration station,” face painting and more at the Grapevine Botanical Gardens. Monarch butterfly releases occurred hourly in the morning, and children of all ages vied for the limited supply, often waiting in line to receive an envelope which contained one of hundreds of Monarchs ordered specifically for the occasion. The release ceremony finished with a countdown–three, two, one. Off they go! WGX139 was among the flyers.

WGX139 arrived in Mexico more than a thousand miles later, at almost 8,500 feet in altitude. It was recovered 138 days after its release at the El Rosario Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Preserve in Michoacán, Mexico, on March 2, 2017.

The amazing journey challenges what Monarch butterfly scientists have been saying for years: commercially raised Monarch butterflies do not migrate.

The conventional wisdom has always been that butterflies coddled in a laboratory setting with ideal conditions such as infinite amounts of milkweed and protection from predators likely would not develop the Darwinian skill set to migrate to Mexico. Scientists have also bandied about different theories about how important the sun’s cues are, and how they are tied to a butterfly’s location and the ambient temperature to which they are accustomed. More than one scientist has told me that a butterfly raised in Florida and released in Texas would never make it to Mexico.

In addition, it’s likely that WGX139 was not raised on milkweed. Bradenton’s butterflies often consume Calatropis gigantea or Calatropis procera, members of the dogbane family. Butterfly breeders sometimes use this African native because it has such enormous leaves and provides ample fodder for hungry caterpillars. It has similar chemical properties to milkweed.

“That’s a pretty interesting event,” said Dr. Lincoln Brower, one of the foremost Monarch butterfly experts in the world. “It shows that they’re adapting to local conditions in Texas, otherwise they wouldn’t get to Mexico.”

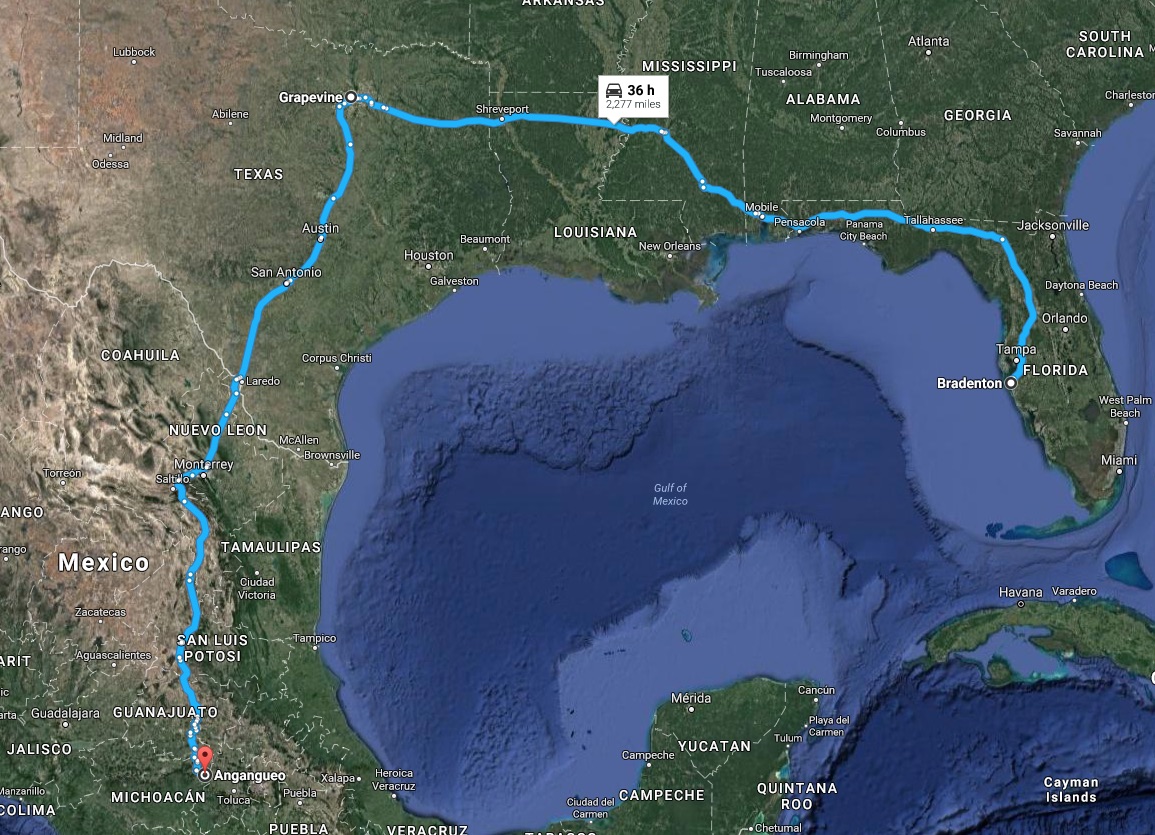

Incredible journey for an international traveler? WGX139 likely traveled from Florida to Michoacán–2,277 miles from birth to roosting sites. Map via Google

“That’s interesting. That’s very interesting,” said Dr. Chip Taylor, founder of the University of Kansas’ Monarch Watch tagging program used by Singleton and thousands of others who participate in the citizen science initiative. “I imagine a few will do it, but I can’t imagine very many of them will do it. It depends on how you handle them and what the temperatures are when they’re released.”

Dr. Karen Oberhauser of Monarch Joint Venture doesn’t think that a single Monarch making it to Mexico should dismiss concerns of disease and the other perceived threats caused by commercial butterfly rearing and mass releases.

When asked to comment, she directed us to a webpage devoted to the dangers of captive breeding and mass releases–disease, dilution of the gene pool, and interference with scientific studies of population dynamics. WGX139’s international travels and arrival in Mexico “doesn’t really argue against these concerns,” said Oberhauser via email.

Monarch caterpillars on Calatropis, a member of the dogbane family. Photo by Connie Hodsdon

Dr. Sonia Altizer of Project Monarch Health at the University of Georgia, was also skeptical. “I agree that some growers are attentive to disease management, which is encouraging to see.

But others are not – and the concerns about disease extend to butterfly enthusiasts who rear Monarchs in large numbers but for no commercial gain.

Hopefully as more people become aware of OE and other diseases, and how to prevent them, the rearing conditions will improve, but my general impression is that there are many more productive ways people can help Monarchs aside from rearing.”

Citizen scientist Singleton has her own theories. She believes some of the butterflies from the Festival lingered to nectar on local flowers and to wait for the wind to shift. Singleton, who was tagging Monarchs back when they still used glue to adhere them to the wings, said she found several Festival-tagged Monarchs in her yard.

Grapevine Flutterby Festival wrangler Jenny Singleton with her grandson, Davis Berg. Photo by Peggy Moore

“I found four or five tagged butterflies from the Festival on my bushes three weeks later,” she said. “I think they hung out and nectared and caught those southbound winds,” said Singleton, recalling “big southern winds for two weeks” in late October.

Connie Hodson, the butterfly breeder who supplied the bulk of the livestock to the Festival, is delighted to know that WGX139 made it to the Mexican mountains. “Not only are our butterflies OE free, they’re super intelligent,” said Hodsdon by phone, referring to Ophryocystis elektroscirrha, the unpronounceable spore-driven disease that often finds Monarchs in crowded conditions.

Hodsdon prides herself on a clean operation and runs her Flutterby Gardens (no formal association with the Grapevine Butterfly Flutterby Festival) with the help of seven seasonal staff from her home on a one-acre lot just north of Sarasota. “We’re really proud of our butterflies,” she said. “Our butterflies are an asset.”

Hodsdon supplied the bulk of Monarchs for our Monarch Butterfly and Pollinator Festival in San Antonio last year. We ordered more than 500 Denaus plexippus from her for our October 22 event, which was modeled after the Flutterby Festival.

David Berman, PhD candidate at Oklahoma State University, is studying late generation Monarch butterflies and parasitoids. Photo by Monika Maeckle

None of our Monarchs were recovered in Mexico, but 20 of them were netted about two miles downstream. Graduate student David Berman from the University of Oklahoma happened to be in town that day performing a study to determine how late generation Monarchs might affect the migration.

According to Berman, 20 butterflies tagged at our Festival on October 22 were netted on the San Antonio River a day later, October 23. None of them had OE, which is one of the major concerns scientists have for commercially raised Monarchs.

That’s because breeders like Hodsdon run a tight shop. She is meticulous and even bleaches the plants that the butterflies eat to rid their food of potential spores, virus or bacteria. Hodsdon teaches a course on how to raise OE-free Monarchs to professional butterfly breeders via the International Butterfly Breeders Association. Her process includes rounds of bleaching, sanitary conditions, gloves and passion mixed with pragmatism.

Flutterby Gardens flighthouse in Bradenton, Florida. Photo by Connie Hodsdon

“Because every Florida Monarch I found in the wild tested positive for OE,” she said. “And not just a little, a lot of OE.” Hodsdon’s appreciation for butterflies is not limited to Monarchs. She raises 20 different species, shipping thousands out each week during high season. “And I’m not getting rich, because it takes so much work,” she said.

So if commercially bred Monarch butterflies can migrate and responsible breeders can raise them disease free, is it possible they could be tapped to bolster the declining migratory population?

The science is unfinished on that, but one can always hope.

Related posts:

- Monarch Butterfly and Pollinator Festival in San Antonio a roaring success

- Agrawal: Milkweeds don’t need Monarchs, but Monarchs need milkweed

- Coming soon: Grupo Mexico copper mine in heart of Monarch butterfly roosting sites?

- Beyond Monarch butterflies: pollinators and politics and Texas Pollinator Powwow

- Q&A: Anurag Agrawal challenges Monarch conservation conventional wisdom:

- Climate change and Monarch butterfly migration symposium tackles tough questions

- Climate change expert Katharine Hayhoe at TribuneFest: “Hopelessness is hopeless.”

- Scientists try to assess Monarch butterfly mortality after Mexican freeze

- How to plan a successful butterfly and pollinator garden

- Mostly native butterfly garden outperforms lawn every time

- Tropical Milkweed: To Plant it or Not is No Simple Question

- How to raise Monarch butterflies at home

Like what you’re reading? Don’t miss a single post from the Texas Butterfly Ranch. Sign up for email delivery, like us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter, @monikam.

I promise I read the whole article. But the one sentence that stands out for me is “The conventional wisdom has always been that butterflies coddled in a laboratory setting with ideal conditions such as infinite amounts of milkweed and protection from predators likely would not develop the Darwinian skill set to migrate to Mexico. ”

Here in southern CA, we have battled that coddled lab setting for years, but I can now see some encouraging signs of being heard.

Good work Wrangler Jenny!

18 years ago five commercially reared monarchs (on non-native tropical currassavica milkweed) from California were shipped to New Mexico for release and five were recaptured at the overwintering sites in central Mexico: http://www.swallowtailfarms.com/pages/educationalproducts_mms.html

Somehow I knew you would weigh in, Paul.

How are you doing these days?

Way to go, Jenny! So proud of your work and its significant results!

You are awesome, Jenny! And a good mother for butterflies.

mom

Ditto what she just said. -MM

I have a couple of Mexican Milkweed plants that are doing very well in my back yard. Now that we are in mid-July, is there any chance I will find any eggs on them? If so I will start looking so I can bring them inside and raise them per the instructions on this website.

Very possible you might find some Queen eggs. Monarchs are also not impossible. Good luck!

Since the summer of 2015 there’s been an ongoing non profit project started in the Midwest to create and test a method to raise monarchs that closely duplicates nature eliminating

the predators that destroy eggs, caterpillars, and chrysalis. This project was initiated by a science teacher and monitored by degreed biologists

to be sure the system produces disease free butterflies released into nature to breed and produce more disease free butterflies. The 10,000 butterflies released this last season were actually more healthy than the butterflies that spent their entire life in the wild. No one participating in this initiative is getting paid. This is being done to produce a system 100s of of thousands of average people can participate in and “easily” produce a minimum of 100 disease free monarchs each season to release into nature to produce another generation and that generation produce another that migrates to Mexico to overwinter. feasibly adding 100 to 200 million more monarchs overwintering in Mexico. I’ve worked with these enthusiasts since the beginning. The website is http://Www.MonarchZones.com. The Manual is here. http://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/540076_ee062ab7510a4dd7963270b0edd3ae32.pdf The brief explanation how the enclosure was developed is here. http://lstrosch.wixsite.com/monarchzones/monarchbiotentWww

Raising and releasing does not address or mitigate the underlying cause of the eastern migratory monarch population decline that occurred between about 2002-2010 which was the near elimination of syriaca milkweed plants from within and around the perimeters of upper midwestern crop fields like this: https://imageshack.com/a/img922/9429/PqmlvH.jpg

Hi Paul, I was hoping I could raise a comment from you. What you say is true to some degree. A couple things. If you look at the most recent. ‘Monarch Watch population graph there’s an Astrix above the 2003 graph. Reading at the bottom a couple things occurred there. The count was taken in November before the monarchs cuddled up a little closer. The count was revised down to 8 after after a recount in January. Chip doesn’t say if all previous counts were made in November including that 18 hectare spike. The other thing of note is after that count the World Wildlife fund got involved in the count. We all know they like doom and gloom for most species they monitor otherwise there wouldn’t need to be a WWF, right ? The average after 2003 has been around 4 hectares. We had that 24 months after the All time low during the minute time numbers gave been counted. Meaning there was plenty of milkweed for four hectares two counts ago and there’s plenty now even if the count turns out to be smaller this year. If you study the USDA major land uses website you will discover the cornbelt cropland count has only gone up 5 million acres from 373 million acres to 378 million acres in the last 25 years. And there’s less cropland in the cornbelt than there was in 1949. As you know, I was driving from New York to Des Moines in the middle of September in 2016. Both sides of I 80 were almost continuous. Abundant Common milkweed with no caterpillar damage and goldenrod in full bloom. Most of the monarchs had already moved south of I 80 by then. What this tells us is there was plenty of milkweed on the landscape because there was a huge amount that wasn’t used for breeding during the season. You will never hear that observation from any of the monarch NGOs or government environmental groups. If monarchs need milkweed they wil find it. If there’s plenty left after the breeding season and they have gone south there is plenty for a larger population. https://www.google.com/maps/d/viewer?mid=1pog1Dkr-1Ie6Pz_hQKud49h1i3s&hl=en_US&ll=35.73257884693918%2C-89.90614416250003&z=5