Texans suffer mightily each winter as “cedar fever” hits the region. The mass appearance of billions of pollen granules from the Ashe Juniper tree, Juniperus ashei, known locally as “mountain cedar,” wreaks havoc on the respiratory systems of locals.

It starts with itchy eyes and runny nose, proceeds quickly to sneezing and wheezing, and can quickly develop into a major sinus infection. As the Dallas chapter of the Native Plant Society commented on Facebook recently in response to an article documenting the seasonal malady: “Anyone else cursing this native?”

Male Ashe Juniper release billions of pollen granules each winter in Texas. The resulting “cedar fever” tortures locals with allergic reactions. Photo by Monika Maeckle

Cedar fever sufferers may soon get some relief, however. Pollen Trackers, a citizen science initiative out of the University of Texas at Austin, is making cedar pollen the premiere focus of a new pollen tracking project.

The program asks volunteers to monitor and report data on local cedar trees to alert the community when they release their pollen into the atmosphere.

“We don’t know yet how much pollen people are exposed to in their daily lives,” said Daniel Katz, a postdoctoral research fellow at the Dell Medical School at the University of Texas at Austin, who’s spearheading the program. He added that predicting airborne pollen concentrations can warn people about pollen hotspots in advance and help them maximize the benefits from their allergy medication.

Female Ashe Juniper flaunt blueberry-like berries favored by birds that typically include a dozen seeds. Photo by Monika Maeckle

As part of their reproductive cycle, male Ashe juniper trees produce small pollen cones, while female trees produce small seed cones that look like blueberries, explained Estelle Levetin, PhD and a professor of biological science at the University of Tulsa who has studied Ashe juniper for decades. Upon maturity, the male trees release billions of pollen granules into the wind –usually on a cold, breezy day. That yellow pollen dust, filled with myriad allergenic compounds, can travel up to 200 miles.

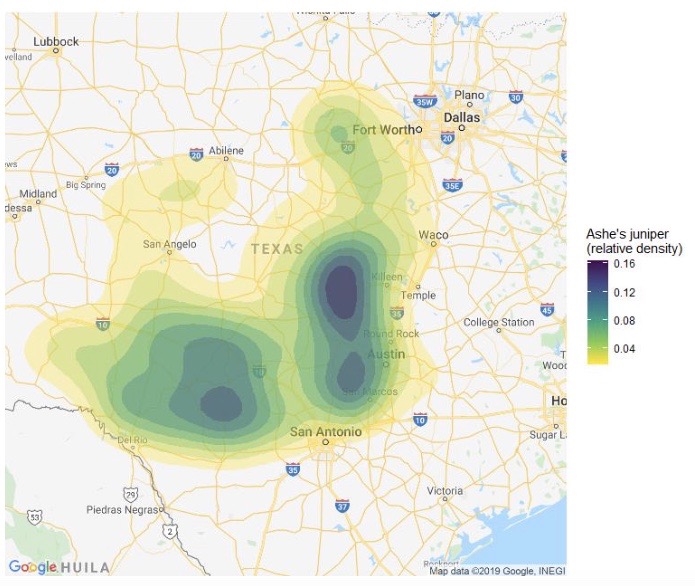

The bushy evergreens are native from southern Missouri to northern Mexico, but are especially dense in Central Texas and the Hill Country, due in large part to flawed land management.

As European settlers occupied the Texas Hill Country and converted native grasslands to farming and grazing, the natural fires that once kept the cedars in check became less common. Since, birds have managed to plant the blue juniper berries everywhere, resulting in some of the thickest stands of cedar in the U.S. See map below.

Ashe juniper density. Map via Pollen Trackers

Cedar fever season typically starts after Thanksgiving and continues through February. Climate change will likely extend the season, though, as warming temperatures increase the trees’ reproductive cycle and boost pollen counts, according to the Fourth Annual Climate Change Assessment.

The Pollen Trackers campaign will help to predict when people are exposed to this highly allergenic pollen, said Katz. Data collected will lay the foundation for a regional “cedar fever” pollen alert system.

Like Monarch Watch or iNaturalist, Pollen Trackers asks volunteers to record observations. Data will be used to formulate allergy forecasts.

The program asks volunteers to monitor and report data such as when pollen is released into the atmosphere. Identification tip sheets with detailed color photos help volunteers determine the stage of the male trees’ pollen cycle. When the cones open their scales and turn orange, the pollen is released.

Those interested can sign up at Pollen Trackers, which is being incorporated into the USA National Phenology Network’s Nature’s Notebook crowdsourcing platform.

Katz explained how Ashe juniper’s “phenomenal amount of pollen production,” combined with its massive tree population and its particular pollen structure creates “the perfect storm of allergies…. That’s why why cedar fever is one of the worst allergies in the U.S.,” he said.

So does he recommend grabbing the chainsaws and clearing all the cedar, as some Hill Country landowners attempt to do?

“I wouldn’t go that far,” he said, noting that pollen-producing male trees would be better candidates for cutting down than clearing cedar indiscriminately.

Juniper hairstreak, which hosts on Ashe juniper, nectars on agarita blooms in the Texas Hill Country, Feb. 2019. Photo by Monika Maeckle

The tree species is an important part of the regional ecosystem. Ashe juniper provides food, shelter, and nesting materials for wildlife, specifically the endangered golden-cheeked warbler. They serve as host plant to the Juniper hairstreak, a green-winged butterfly that feasts on its leaves. Ashe juniper trees also provide a unique, rich bed for particular native plants that thrive in its mulch.

“Trees do a lot of benefit for us. … Allergenic pollen is just one of the things we need to weigh,” he said.

Related posts:

- At war with Agave americana: tenacious plant resists chainsaw, digging, fire

- Trinity Students continue battle with Johnson Grass

- New study: nectar plants more important than milkweed for Monarch butterfly migration

- How to plan a successful pollinator garden

- Mostly native urban butterfly garden outperforms lawn every time

- IH-35 to Become Pollinator Corridor for Bees, Butterflies and other Pollinators

- Endangered Species Act: Wrong tool for the Job of Monarch butterfly Conservation?

- Texas Butterfly Ranch Native Texas Milkweed Guide

- A Year in the Life of a Mostly Native Urban Butterfly Garden

Like what you’re reading? Don’t miss a single post from the Texas Butterfly Ranch. Sign up for email delivery below, like us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter, or Instagram.

Wonderful post. Thanks for sharing it!