Congratulations, 2012, you’re the hottest year on record!

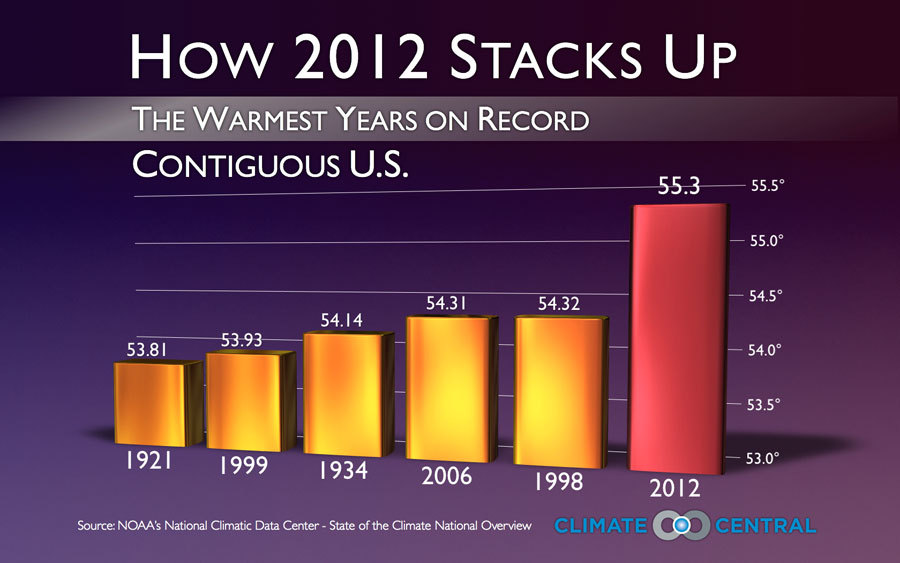

The National Climate Data Center, released data this week showing that temperatures across the U.S. averaged 3.2 degrees above their 20th Century average. Nineteen states–including Texas–had their highest annual average temperatures ever recorded.

Hot enough for ya? Climate data shows 2012 was 3.2 degrees hotter than any prior year. Chart via NOAA

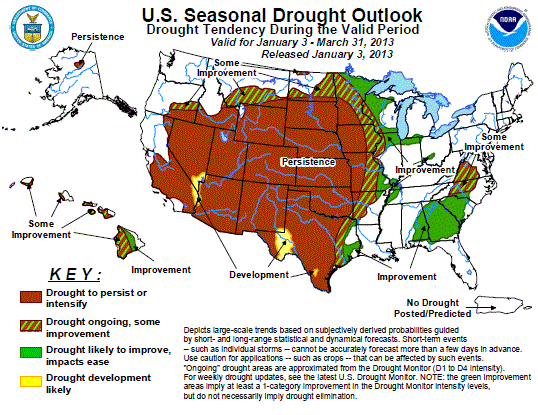

Last year’s wet winter and mild spring fooled us into thinking that the drought and extreme heat were behind us. But the last three months of 2012 were some of the driest in history and predictions are rife that 2013 will bring continued, possibly intensified drought.

Drought Outlook 2013: more and maybe worse.

In our front yard, “winter” visited for a few days following Christmas, but the “freeze” didn’t even die back our Frostweed plants. Our milkweed, pruned in early December, sports new chutes, suggesting our downtown environment is even warmer than thermometers reflect. Over at the Milkweed Patch on the San Antonio River Museum Reach, we observed monarchs and Queens in abundance in late December.

The continued drought and warm temperatures beg the question: Will monarchs and other butterflies continue to migrate if they and the plants that sustain them can survive warm winters?

Monarchs and other butterflies are occupying the Milkweed Patch at the San Antonio River Museum Reach year round. Photo by Monika Maeckle

“Climate change – in the near term – is not going to change the monarch migration,” Chip Taylor, founder of Monarch Watch, relayed via email. Over the long haul, though, it’s inevitable that climate change, coupled with the decimation of the Mexican roosting sites, pervasive insecticides, and an increase in genetically modified crops will decrease the numbers of monarchs and impact their migration habits.

Karen Oberhauser, PhD in Ecology at the University of Minnesota, suggested that monarchs “might not need to (or be able to) move,” given the changing climate. “But that could expose them to potentially lethal conditions, when, for example, the southern US experiences an unseasonal freeze,” she added.

Oberhauser, who has been studying monarchs since 1984, also mentioned undesirable colonies of Ophryocystis elektroscirrha, or OE, a protozoan disease that infects monarchs and other milkweed feeders. OE is present in the landscape but seems to especially flourish on Tropical milkweed in southern climates late in the year. In colder climates and the wild, milkweeds die off in the winter, apparently purging OE to a large degree. But in places where freezes don’t kill off milkweed, OE becomes a problem and can be lethal to Monarchs.

Eeeew! OE spores look like little footballs next to monarch butterfly scales–photo courtesy of MLMP

“Some species are increasing their range, but one problem with that is that other species that they need to survive might not move at the same rate,” said Oberhauser.

“Just because it warms up, doesn’t necessarily mean monarchs. . . won’t migrate, ” John Abbott, Curator of Entomology for the Texas Natural Science Center at the University of Texas at Austin, wrote to us in an email. “It may be so genetically programmed, that they have no “choice.”

The Brown Argus Butterfly has adapted well to climate change by changing its diet and expanding its range by 50 miles. Photo via cum bria.org

One butterfly species in England has fared extremely well in the face of climate change. The Brown Argus butterfly has increased its range in England 50 miles north in the past 20 years thanks to warming temperatures. According to a study made possible by English citizen scientists over many years, the Brown Argus has flourished because it adapted its diet and now eats wild geraniums, which formerly only thrived in especially warm summers. Prior to the warmer weather, Brown Argus caterpillars ate primarily Rock Rose.

The Brown Argus’ adaptation to a new host plant and that plant’s wider availability caused by warmer temperatures thus allowed the butterfly to expand its range at twice the average rate of other species, the study found. Change or perish.

“Sudden changes resulting in a species being in an area where it wasn’t or when it wasn’t previously will almost invariably have an affect on other species,” cautioned Abbott. “So it’s a cascade.”

According to the IO9 blog, a website devoted to science, science fiction, and the future, insects are well poised to take advantage of climate change. Why? Because they are well suited to quick adaptation and in the case of those with wings, able to move to new environments. And, as cold blooded creatures, they will have a longer eating/growing/reproductive season with longer, warmer seasons.

Embrace it. Odds are more mosquitoes, ticks, fire ants–and hopefully butterflies–are coming our way, if this warmer weather pattern continues. One sure thing: change will continue to be the only constant.

Leave A Comment