Dr. Anurag Agrawal has a bit of a contrarian streak. Named the recipient of the prestigious MacArthur Ecology Award earlier this year, he was lauded for “opening up new research themes” and continuing “to push the envelope using novel approaches” to science, teaching and building community.

Dr. Anurag Agrawal –PHoto by Frank DiMeo

Take a paper Agrawal and a team of researchers published in April, for example.

Titled “Linking the continental migratory cycle of the monarch butterfly to understand its population decline,” Agrawal dared to suggest that the intense focus on milkweed in Monarch butterfly restoration efforts might be misplaced. Solutions that address habitat fragmentation and increasing the availability of late season nectar plants should receive more attention, he proposed.

Born in Allentown, Pennsylvania, Agrawal currently serves as Professor of Ecology and Evolutionary Sciences and Faculty Fellow at the Atkinson School of a Sustainable Future at Cornell University. He’s married to fellow Cornell professor Dr. Jennifer Thaler, an insect ecologist, and the couple have two children, Anna and Jasper. Agrawal attributes his initial interest in science and plants to his mother’s intense love of vegetable gardening.

“Planting milkweed is probably not a bad thing to do but it’s not going to increase populations or save them from demise,” said Dr. Agrawal in a nine-minute video released in conjunction with the paper.

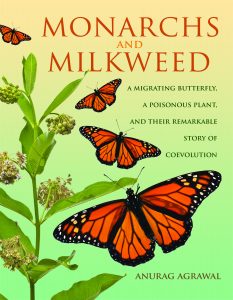

The paper rocked the “Monarchy” as he calls the scientific and citizen science communities devoted to the migrating insects in a soon-to-be published book, Milkweed and Monarchs: A Migrating Butterfly, a Poisonous Plant, and their Remarkable Story of Coevolution. The book will be available in April 2017. If all 296 pages are as readable and interesting as the first chapter, which you can read for free at the Princeton University Press website, Agrawal will have a butterfly bestseller on his hands.

Agrawal will be in town for a session at the San Antonio Book Festival APril 8. Come join us and get your book signed.

Agrawal has called the decline of the Monarch butterfly migration a “very gnarly problem,” and consistently gives kudos to citizen scientists for contributing to our understanding of them. He often cites a need to “get the science right.”

That sounds like an honorable goal.

Let’s hear more from Agrawal, below.

Q: Did you get a lot of flack for your contrarian view on the priority placed on milkweed in Monarch restoration efforts?

Agrawal: I did get a lot of flack. And I would say that it was pretty interesting, too, because a substantial amount of the flack was off-the-record.

We had sent the manuscript to several Monarch researchers and many of their comments substantially improved the study. But there was a lot of pushback from very prominent research before we got it published. They were asking, ‘Do you want to be the person that derails Monarch conservation? You will appear to be in bed with Monsanto.’

It’s nice to think about science as a fact-based enterprise, but I was really surprised at the extent to which there was a strong agenda and some folks were not open to alternate interpretations of the data and the conventional wisdom.

I was anxious to see what would happen once the paper was published. And I was glad to see that when some of the senior Monarch researchers were asked, they said they didn’t agree–but they were far less bold in their public disagreement or criticism of the work.

My hope is that the study contributes a little to a change in perspective. Any good scientist would agree there are many factors and many causes that contribute to Monarch decline and getting the science right is critical to having a positive impact.

Q: Is it not the nature of the evolutionary cycle for creatures to STOP migrating if they can secure the food and reproductive resources they need locally?

Predators like the Tachinid fly serve the evolutionary purpose of keeping the Monarch population in check. Here, Tachinid larvae next to dead Monarch caterpillar. Photo by Monika Maeckle

Agrawal: For Monarchs, it’s known that the ancestral populations are migratory but that there are nonmigratory populations in Florida, Spain, Hawaii and elsewhere. Some new populations will evolve to be non-migratory, including some non-migratory populations in Mexico.

Scientists believe that migration evolves to take advantage of a large un-utilized resource in some seasons. For example, movement north from Mexico and the southern U.S. in spring evolved to take advantage of abundant milkweeds in the Midwest and Northeastern USA.

Migration is certainly an evolvable trait. In many of the articles I’ve read, almost everyone agrees Monarchs are not under any threat to go extinct; but the migratory phenomenon, one of the most spectacular in the world, may be at risk of going extinct.

Q: Is it arrogant of us to work to perpetuate the Monarch migration for the sake of our joy and fascination of witnessing the natural spectacle? What would the butterflies think if they had the option to reproduce and feed locally rather than migrate thousands of miles?

You’ve asked a really good question: is it arrogant for us to expect the migration to continue forever? The reason people worry about its loss is that we have to ask, to what extent is that loss driven by human consumption of the planet?

The world is changing on its own, organisms are evolved creatures and go extinct all the time; the pace of that extinction is much more rapid in recent years than in the pre-industrial past. It has been likened to the pace of mass extinctions caused by events like asteroids hitting the planet. If that’s the case, and we have some control over it, then my answer is quite different than if the decline is due to “natural causes.”

Q. What is your view on Tropical milkweed, Asclepias curassavica, and advice from many scientists to chop it down in the late summer and early fall? What about other milkweeds that continue growing through the season in warm climates?

Agrawal: We just don’t really know. That hits on a key issue: what causes the break in reproductive cycle–is it the presence of milkweed flowers in general, or is it something specific to Tropical milkweed?

Tropical milkweed: The debate continues. Photo by Monika Maeckle

We don’t know all the reproductive cues that affect Monarchs. Scientists discouraging “non-native” milkweeds are sticking with the precautionary principle–i.e., natives are expected to keep monarchs on track to continue their cycle.

What is a gardener to do? Plant native milkweeds.

Habitat protection is a good thing. But there are a lot of unknowns. During the southern migration we’re just starting to get some sense of what happens in Texas–but we have very little information about what happens for the last 800 miles. That last third in Northern Mexico is when they’re struggling with wing wear, with lack of fuel (nectar), and we have very little data on that leg of the journey.

Q. Do you think that the rearing and release of Monarchs by citizen scientists and enthusiasts is harmful or helpful to the cause?

Agrawal: It’s not something I have a scientific opinion on. It’s a double-edged sword in some ways… I’m very pro public engagement with the natural world, but I’m personally not that fond of the rear-and-release for the purpose of “helping” a species. It hints of a little bit of arrogance. We’ve created some problems and now we’re going to solve it by just raising them to make up the difference?! That’s not how nature works.

What makes people think that rearing them in cages is going to increase the abundance of the species? Look at the Bald Eagle. It wasn’t rearing them in captivity that saved them; it was improving habitat, understanding where they want to nest that made the difference.

We all desperately want to help, but I’m not sure that getting in the drivers’ seat is the most sensible approach. I would argue from the perspective of environmental education it makes a lot of sense–to be in Nature, to experience it, it’s something we can do.

Q. Are you aware of the recent Monarch zones efforts by folks in Iowa whereby volunteers raise and release Monarchs using an outdoor biotent natural rearing protocol? Is that any different, better or worse than enthusiasts or commercial breeders raising and releasing butterflies?

Agrawal: Natural is often better. There’s pretty strong evidence that suggests exposure to ultraviolet light kills off some of the parasites and that the natural cues of sunlight will increase the probability of the Monarchs migrating. But in Nature, more than 90% don’t survive!

It’s worrisome to take natural filters out of the life cycle that natural predation provides.

When a seedling in a forest makes it to be an adult tree it’s a one-in-a-million event. It’s the one individual in the snowstorm of acorns that wasn’t eaten by squirrels at the right place at the right time that makes it.

The life of a Monarch is the same, in a way. Of those 400 million butterflies in Mexico, only a fraction made it. For the population to be stable, there’s a biological filtration process that creates resistance to predators. Mass rearing removes that filter.

Q. What is the one most important thing gardeners, citizen scientists and regular folks can do to help pollinators and Monarchs?

Agrawal: Something they can do is what they don’t do: don’t spray pesticides around their homes. Having a few more weeds around allows some diversity there, which is likely to protect the animals that visit those plants.

The home gardening movement has all kinds of benefits–reduce lawn and reduce consumption.

Related posts:

- Climate change and the Monarch butterfly migration symposium tackles tough questions

- Climate change expert Dr. Katharine Hayhoe at TribuneFest: “Hopelessness is hopeless.”

- Coming soon: Grupo Mexico copper mine in heart of Monarch butterfly roosting sites?

- Scientists try to assess Monarch butterfly mortality after Mexican freeze

- At least 1.5 million Monarch butterflies perish in freak Mexican snowstorm

- How to plan a successful butterfly and pollinator garden

- Mostly native butterfly garden outperforms lawn every time

- Late season Monarchs create gardening quandary

- Tropical Milkweed: To Plant it or Not is No Simple Question

- How to raise Monarch butterflies at home

Like what you’re reading? Don’t miss a single post from the Texas Butterfly Ranch. Sign up for email delivery, like us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter, @monikam.

I think the right question were ask of this author. Additional questions might be; 1) What has caused the population in Mexico to go from .67 hectares (2013-14) to 4 hectares (2015-16) ? Monarch Watch in January 2016 said no significant native milkweed had been planted. 2) Could the return to normal rains after a catastrophic drought in Texas and the Midwest caused the recent decline and recent increase ? Sources who have spent years at the sanctuaries in Mexico have recently estimated monarch populations have increased over last year. Official numbers in the future will reflect how much increase. 3) If non-native fire ants have increased mortality of monarchs as outlined by William Calvert can the predator protected raising and releasing of monarchs in mass help offset the loss ? I think it’s a fair question to ask as most involved in monarchy rely on the doom and gloom

of the monarchs migration for their stances. In light of the fact there has “never” been any significant human involvement in planting habitat and a 600% increase in monarchs over the last 24 months, is the premise the monarch migration is in any danger a legitimate stance ?

I would argue that “getting the science right” as to whether the eastern migratory monarch population decline is due to a decline in milkweed or nectar plant abundance is not crtical because it’s not ever going to be logistically feasible for monarch enthusiasts or scientists to conduct “annual milkweed and nectar plant patch/stem counts” on even a county – let alone statewide – scale to obtain baseline plant stem abundance data. So because baseline abundance data will never be obtainable it will likewise never be possible for the conservation researchers and groups to tell us whether the number of milkweed & nectar plant patches/stems has actually been increasing over time in any County or State as a result of natural or man caused “restoration and recovery” efforts.

Good point Paul. Of course numbers are rebounding in Mexico the only place we can observe millions in one place. Like any plant, the number of stems and leaves a milkweed plant has is directly related to how much sun and rain it gets. If it rains twice as much one year as the year before that plant has many more stems and leaves.

If the people in charge of our government decide there’s not enough milkweed and encourage the right “scientists” to agree and spread that through the U S average people are going to believe it unless they go out and look and see there’s plenty. Average people have gone out their doors all over the country and found milkweed growing everywhere and have ask their friends and put it on social media Now most people in monarchy are raising and releasing various numbers of butterflies. It’s fun ! Like raising guppies only better. People are believing their own eyes. Once the people in charge of monarchs heard this going on all of the sudden milkweed was “fragmented” on the landscape so if you and your friends see it it doesn’t mean it’s where it needs to be 😉 even though these same people used to say if monarchs need milkweed they will find it. I traveled 4800 miles on the eastern range of the monarch this season and believe my own eyes. There’s an abundance of milkweed and nectar plants from Des Moines to Connecticut and south to San Antonio. I love monarchs and all butterflies and nature in general. I live on acreage in one of the most remote hill country locations west of Austin close to Balcones Canyonlands refuge and Lake Travis.

Over-population of white-tailed deer in the central flyway decimate nectar plants in the fall.