A State investigation is underway at a bat cave near Mason, Texas, after the spraying of pesticides by the neighboring exotic game ranch wafted onto the nature preserve, threatening harm to visitors and the 1.6 million Mexican free-tailed bats that visit there each summer.

While the game ranch’s manager has acknowledged and pledged to correct what he called “a mistake,” larger implications about the pesticide’s effect on the bats remain unclear.

Eckert James River Bat Cave Steward Vicky Ritter gives a bat talk on July 21, 2018. “If this happens again, I will die,” she said. Photo by Monika Maeckle

On Saturday, June 29, as often happens on summer weekend nights in the Texas Hill Country, a small crowd of 20 nature lovers gathered at the Eckert James River Bat Cave. Cave Steward Vicky Ritter had opened the gates around 7 p.m. for visitors, who navigated the trail to the intimate natural amphitheater that serves as a showcase and seasonal home to the bats every summer.

The maternal colony almost doubles in size as the summer progresses and makes for a unique natural spectacle. Female bats arrive pregnant from Mexico in March and typically give birth in late June. After five or six weeks of nursing, baby bats join their mothers in nightly outings to consume two-thirds their body weight in insects each evening. Mosquitoes, moths, and other bugs are on the menu. The insect-eating machines also disperse seeds and pollinate agave, from which tequila and mezcal are made.

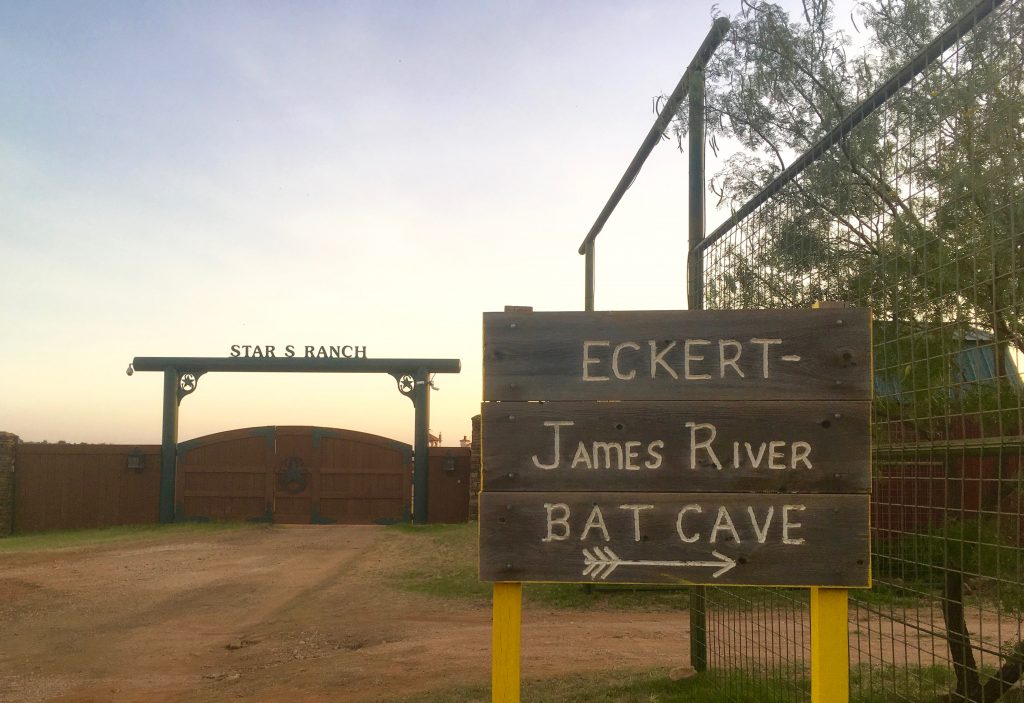

As folks found a seat on wooden benches to hear Ritter’s educational talk and await the spectacular whirlwind emergence, a cloud of pesticide wafted over from the neighboring Star S Ranch. The 14,000-acre exotic game hunting retreat bills itself as a “true Texas safari” and shares a fence with the eight-acre preserve. The bat cave entrance sits about 200 feet from the ranch’s property line.

The Eckert James River Bat Cave Preserve is surrounded by the Star S Ranch, an exotic game hunting retreat. Photo by Monika Maeckle

Coughing and gasping, pregnant women, children, and babies inhaled the insecticides as they ran for their cars.

“This is the third time this has happened,” Ritter told visitors in a harrowing account on July 21, adding that she has survived double pneumonia. “If this happens again, I will die,” she said.

Following the incident, The Nature Conservancy, which owns the preserve, took the unprecedented move to close the cave for two weeks during peak visitor season. On July 11, a notice appeared in the Mason County News stating that a neighboring landowner had treated his property with a fog pesticide while guests were gathering for the nightly bat emergence.

The bat cave reopened July 18, and a Texas Department of Agriculture investigation is underway.

Eric White, ranch manager for the Star S Ranch, attributed the incident to a “miscommunication” in a phone interview this week.

“We made a mistake in front of the whole world, and we’ve corrected it,” said White, adding that he, the ranch, and its owner William Scott of Houston, are “pro bat cave.” White said the ranch has generally abided by a policy of refraining from aerosol pesticide spraying while people are present at the cave.

The ranch routinely fogs deer and other game with insecticides during the hot summer months to protect livestock from pests like ticks, midge flies, lice, and mosquitoes, he said. The Star S Ranch supports itself selling wild game hunts like ibex, aoudad, gazelle, zebra, and white-tailed deer for up to $25,000 a piece. It also sells breeding stock of exotic game. “Hunting pays most of the bills,” White said.

The pesticide used – Permethrin, from the pyrethroid family – is considered one of the safest for human beings. According to the National Pesticide Information Center, pyrethroids are synthetic chemicals that act like natural extracts from the chrysanthemum flower. They are used in flea collars and are considered safe for use on food and feed crops, ornamental lawns, on livestock and pets, in structures and buildings – even on clothing.

Permethrin is deadly, however, to honeybees and most insects. It’s also toxic in aquatic environments. The James River borders the Star S Ranch for six miles on the eastern side of the property and the bat cave sits within a half mile of the waterway.

While Permethrin is considered safe for human beings when applied properly, its impacts on bats have not specifically been tested.

Joy O’Keefe, associate professor in the Department of Biology at Indiana State University and director of the Center for Bat Research, Outreach, and Conservation, said that bats are generally exposed to pesticides through the consumption of insects carrying pesticide residues.

“Because individual bats eat many insects each night, pesticides can accumulate in bat tissues and have lethal or sublethal effects,” O’Keefe said via email.

Several studies have demonstrated declines in bat populations attributable to the use of organochlorine pesticides like DDT – and those pesticides have been detected in bat tissues even 20-30 years after the substances were banned, O’Keefe said. “We know less about the effects of pyrethroid pesticides,” she added.

She also pointed out that pesticides tend to accumulate in fat tissue.

“This means they may be passed on to nursing pups from adults, as milk production draws on fat stores. Stored fat is also burned during migration and hibernation, so effects may occur several months after exposure.

“It’s ironic that we apply pesticides where there are millions of bats, as the bats themselves provide free pest control in the area surrounding their roost.”

She suggested farmers and ranchers consider taking steps to attract even more bat species to their lands for more sustainable control of pestilent insect populations.

Baby bats like this one, often have a hard time flying and stay close to the cave. Note: the bat took off eventually. Photo by Monika Maeckle

Renowned bat expert Merlin Tuttle, founder of the conservation organizations Bat Conservation International and Merlin Tuttle’s Bat Conservation, expressed similar concerns about aerosol spraying of pesticides, alluding to the “pesticide treadmill.”

The term indicates a situation in which landowners must continually ratchet up their use of pesticides as insects develop resistance with repeated applications and the resulting elimination of natural predators.

“You end up killing off the natural enemies of the pest more than the pest itself,” Tuttle said. He echoed concerns for the juvenile bats. Baby bats stay close to the cave when learning to fly, he said, thus the possibility of them consuming sullied insects would be greater closer to the Star S Ranch.

The report on the investigation by the Texas Department of Agriculture is expected by Sept. 1.

NOTE: A version of this story first appeared on the Rivard Report.

Related posts:

- Public hearing in Austin: “Texas beekeepers relying on honey production are in peril.”

- Butterflies without Borders Symposium tackles tough questions

- Monarch Butterfly and Pollinator Festival Soars in San Antonio

- Five Monarch Butterflies released at San Antonio festival make it to Mexico

- 300for300 Tricentennial pollinator habitat initiative announced for San Antonio

Like what you’re reading? Don’t miss a single post from the Texas Butterfly Ranch. Sign up for email delivery below, like us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter, @monikam.

Leave A Comment