Late November means “slow season” at Flutterby Gardens, a commercial butterfly farm in Bradenton, Florida. But that doesn’t mean Connie Hodsdon can sleep in.

Hodsdon has monarch eggs to roll. The pentas, one of her favorite nectar plants, need to be clipped, dipped in root stimulator and transplanted. And the raised beds could use a fresh layer of mulch. Her plant technician, Chris Bernhard, can handle those chores. The butterfly farm’s other staffers will manage caterpillar feeding, cage cleaning and milkweed bleaching.

Fedex will be here at 5 PM, so today’s orders must be prepped for safe transport. Hodsdon prefers to do this important work herself.

She plucks the butterflies from the flight tent, feeds them a special fructose nectar mix, waits for them to flush their intestines, tucks them carefully into glassine envelopes, and arranges the precious cargo around cardboard and ice packs so they “sleep” while traveling. She makes sure that the cardboard separates the icepacks from the glassine envelopes, so as not to cause condensation and possible harm to the livestock. Later, in the evening, Hodsdon will check her email, glance at Facebook, log her orders in Quickbooks and make a list of needed supplies.

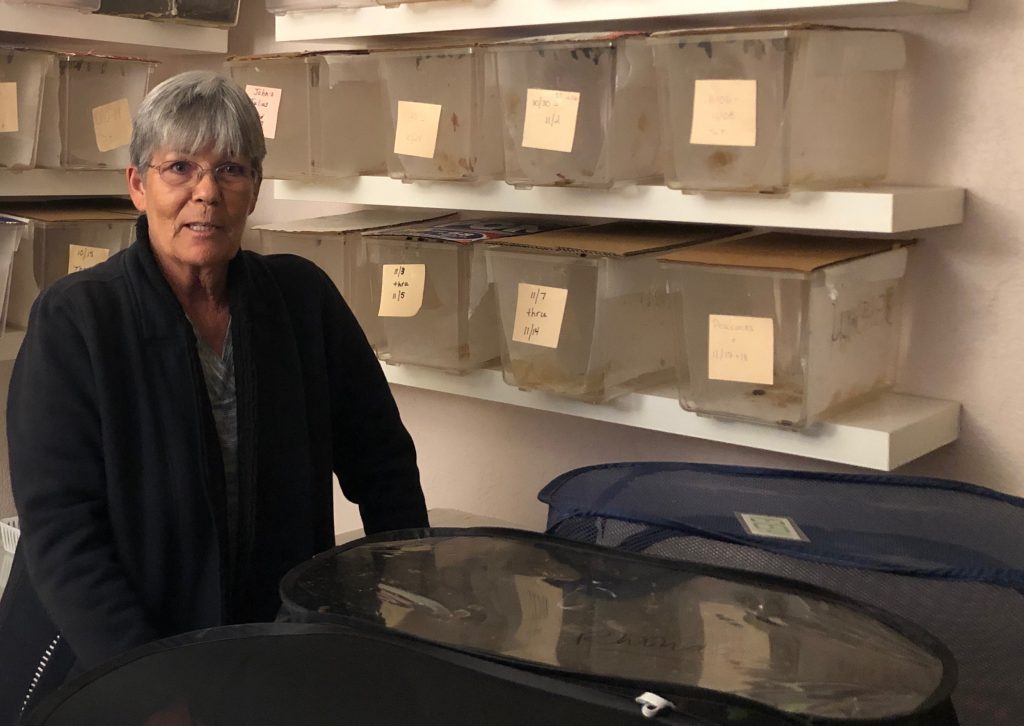

Hodsdon explains her “do it right” approach to breeding in her eclosion room. Photo by Monika Maeckle

“You have to love this or you wouldn’t do it,” said Hodsdon, who’s been breeding butterflies full-time since 2006. And at age 68, the petite, no-nonsense former insurance agency owner has no plans of stopping any time soon. “I’ll do this ’til I can’t do it any longer. I love it,” she said.

Hodsdon first became entranced with lepidoptera as a child in Ohio. She found some spikey, bright green caterpillars noshing on oak leaves and brought them in the house. They morphed into cocoons and spent weeks at the bottom of a box.

“What? That’s my caterpillar?” she wondered aloud.

When the cocoon emerged as a glorious Polyphemus moth with its dramatic eyespots and lush antennae, she was hooked. Soon, she was crafting a butterfly net out of a coat hanger and an old fishnet her father had trashed.

Decades later, after moving to Florida, she started the first chapter of the North American Butterfly Association in Bradenton. Field trips, slideshows and butterfly counts fueled her interest. She started a butterfly garden landscaping business, Flutterby Gardens of Manatee, in 1999, while continuing to run her insurance agency. The landscaping business evolved into a butterfly breeding operation.

Hodsdon was recently name executive director of the International Butterfly Breeders Association (IBBA), an international professional butterfly farming trade association that has 100 members around the globe. She formerly served as IBBA president but the new role puts her in charge of teaching IBBA members “how to do it right” when it comes to butterfly breeding. She is known for her meticulous best practices, not only because it’s the right thing to do, she said, but because it makes business sense.

Her reputation for clean breeding has earned her farm some discriminating customers, including Chip Taylor of Monarch Watch, and Milkweed and Monarchs author Anurag Agrawal of Cornell University.

“She has a great reputation,” said Taylor. Agrawal described Hodsdon as “very reliable.” Both scientists tap Flutterby Gardens for monarch butterflies to be used in experiments. “Connie is really really good at what she does,” said IBBA president David Bohlken.

Hodsdon also supplies the butterflies for San Antonio’s Monarch Butterfly and Pollinator Festival, hosted by the Texas Butterfly Ranch. The event celebrated its third year October 19 -21. Five of the butterflies Hodsdon supplied for the 2017 Festival were recovered on the forest floor of the roosting sites in Mexico earlier this year.

A late November visit to Hodsdon’s farm finds me on a quiet bungalow-lined street, walking up a sidewalk rimmed with still blooming Casia trees (host plant to Orange and Yellow Sulfurs). Navigating her six dogs and Austin, her 17-year-old cat, Hodsdon and three staff members move among her six work rooms and flyhouses this unseasonably cold day.

She notes that the purple-blooming Ruellia (host plant to Malachites and Common Buckeyes) is getting a bit raggedy. “Time for a trim,” she said. The front yard is filled with Giant milkweed, Calatropis gigantea, which exists outside the Asclepias family we generally use to define milkweeds. Yet the nonnative plant is a favorite for monarch butterfly egg laying as well as fodder for hungry caterpillar offspring.

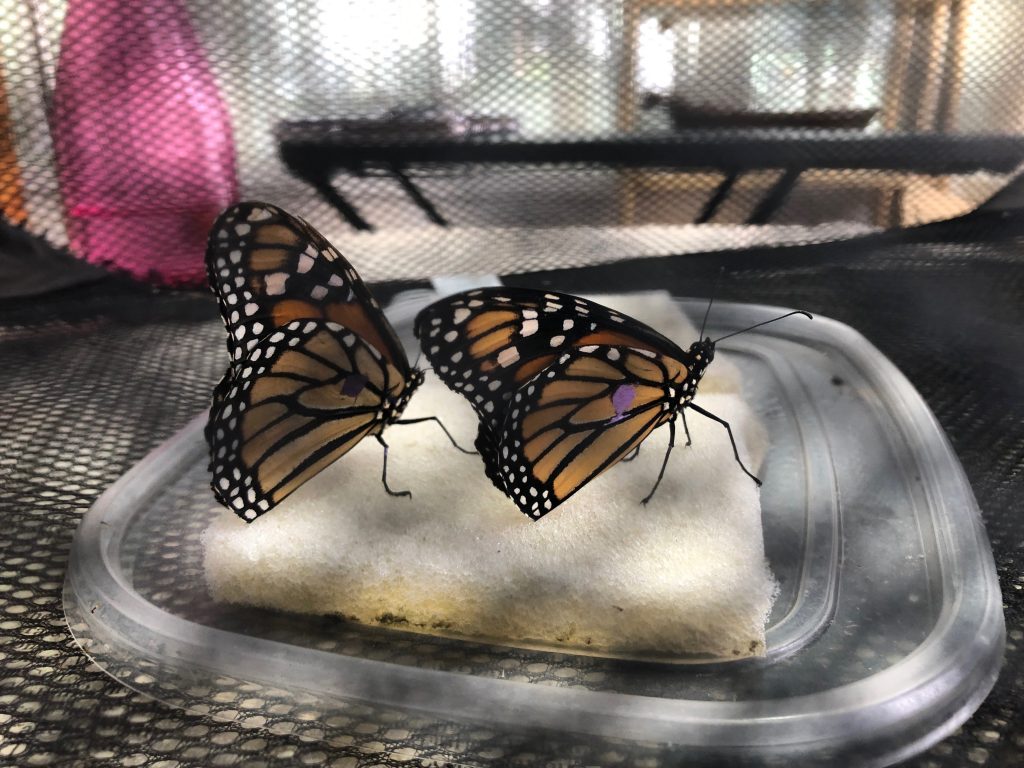

Hodsdon’s custom butterfly feeder. Photo by Monika Maeckle

“I hate Tropical milkweed,” said Hodsdon, of Asclepias curassavica, the most common and often controversial milkweed available to hobbyists in the U.S.

Hodsdon discontinued using Tropical milkweed several years ago, once she learned about Giant milkweed. Tropical milkweed is “too much of an aphid magnet” and the leaf mass is tiny compared to the grandeur of Giant milkweed, she said, adding that a good butterfly farmer needs to be equal parts botanist and caterpillar caretaker.

Calatropis gigantea, grows up to six feet tall and its leaves are massive compared to the thin blades of Tropical milkweed. Native to Africa, monarch butterflies and caterpillars in Florida use it gladly for egg laying and food, respectively. Breeders appreciate its leaf mass as monarch butterfly “cat food.”

Hodsdon shows abundant resourcefulness in tackling the unique challenges of butterfly breeding. Bleaching eggs, milkweed, cages and tools has presented obstacles in durability for many store-bought implements. That’s why she’s fashioned her own egg laying cages from mesh netting, wire and adhesive extruded from a glue gun. The repeated bleaching required to raise healthy, OE-free monarchs wrecked store-bought models.

She also recycled plastic jugs and PVC pipe to create durable nectar feeders for the butterflies, since again, constant bleaching to prevent disease took a toll on mass-produced models.

With a deep-throated chuckle, Hodsdon trots out her butterfly farming “uniform”–a pair of ragged shorts and a t-shirt, both garments blotted white by repeated encounters with Clorox. “There’s no reason to wear good clothes,” she pointed out.

Her years of experience have also resulted in some new techniques for mass rearing. Typically, we’re told that once in the chrysalis stage, monarchs must hang vertically for their wings to form properly. Not so, said the expert breeder.

Hodsdon lets the jewel-green chrysalises lay on the bottom of a sterilized net cage. When they’re ready to close, they simply pop out.

Hodsdon lets monarchs eclose laying on the bottom of a sterilized black net cage. “The strong ones will climb right up.” Photo by Monika Maeckle

“The healthy guys will climb on top, and eventually up the side of the cage,” she said, as we witnessed a fresh monarch butterfly doing exactly that. She confessed that monarchs are not her favorite species, although they are the most frequently requested as Flutterby Gardens livestock.

“They’re easy to manage, have a good shelf life, they’re strong, healthy and still fly in the cold,” she said pragmatically. Her favorite butterfly: the Eastern Black swallowtail. “I’ve loved them since I was a child, due to the blue on the female and their darling tails,” she said.

TOP PHOTO: Two gravid females are marked with fingernail polish and housed in a separate egg laying cage at Flutterby Gardens. Photo by Monika Maeckle

Related posts:

- Five monarch butterflies tagged and released at San Antonio Festival made it to Mexico

- A tense online debate: raising monarch butterflies at home

- Coverage of San Antonio’s Monarch Butterfly and Pollinator Festival

- Weird, late monarch butterfly migration finally reaches Mexico

- Monarch Zones: bold move or bad idea for expanding monarch butterfly population?

- How to plan a successful butterfly garden

Like what you’re reading? Don’t miss a single post from the Texas Butterfly Ranch. Sign up for email delivery at the bottom of this page, like us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter, @monikam.

I love butterflies! They’re definitely my favorite animal.

I need to know how to help my freshly hatched monarch butterflies indoors during cold weather. I live on the Central Coast of California. Weather is fairly mild compared to other parts of the US. This year temps have been in the 50’s during the day dipping to the 40’s at night since April when normally day temps would begin to rise but it hasn’t.

Currently for the past month I have been caring for 38 cats I found on my milkweed the middle of April. I now have them in a netted cage and they are starting to hatch. 3 have hatched in in the past 2 days with quite a few more getting ready.

I don’t know what I can do to help them along to till the temps raise a little more. Today is is cloudy and intermittent rain. I have a potted milkweed plant in the cage with flowers that they can take nectar from but they are just walking around on the netting and still most of the time.

Hi, Connie! Just stumbled upon Texas Butterfly Ranch and laughed at the lifetime “parallels”! Growing up in New York (I’m 75), I collected, then raised Polyphemus, Cecropia, LOTS of “polyxenes”, Monarchs, etc., etc.! Almost went into a career in entomology, but became a teacher instead. All those years I (we) taught our kids, then our GRANDkids the wonders of butterflies and moths! Today we still annually raise blacks, spice bush, and several dozen Monarchs as well as some beautiful Lunas as a family hobby. Truly a lifetime fascination!

Although very aware of the OE problem, we DO “ bleach” and turn out some healthy releases – to “ do our part” for the “ Danaids”! I got some good tips from your article – especially the

C, gigantea! Looking forward to your next posting! Keep up the good work!

Mark Schweibish

N. Y.