Austin environmental planner and ecologist Elizabeth McGreevy suggests in a compelling new book that Texas landowners and ranch managers put down their chainsaws and rethink their relationship with Ashe juniper, locally known as Mountain Cedar.

Elizabeth McGreevy

Her case for reason faces challenges. As she states in her introduction, “The Trees We Love to Hate,” emotions often run high when considering the Mountain Cedar.

“It has always amazed me to hear the snarls emitting from otherwise docile people as they denounce the trees,” she writes. “When I dispute their beliefs…people have hurled lunch bags at me, hung up on and me and mocked me during presentations. I have even been called a heretic. Never before has there been a more determined group of people than those set on eradicating a single species of tree. We have forgotten that in bygone days, the tree was held in high esteem.”

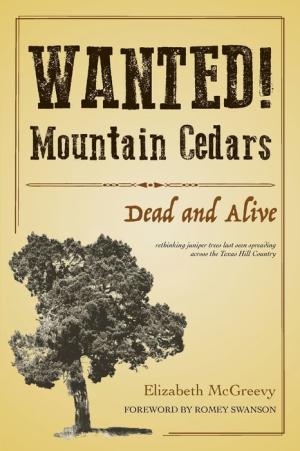

Her 578-page paperback, WANTED! Mountain Cedars, Dead and Alive, lays out the case for reconsidering Texas’ most hated tree. Using accessible language, historic black and white photographs, and hundreds of annotations and scientific citations, McGreevy dispels the myths about the maligned native juniper.

For those unaware, Ashe juniper trees, aka Mountain Cedars, cover millions of acres in Texas. The tree has been accused of being a useless, non-native, water-hogging species that competes with native grasses, forbs, and oaks to undermine the landscape. The tree is also the source of an irritating pollen that results in “cedar fever,” an affliction of allergy sufferers each fall.

Juniper hairstreak, which hosts on the reviled Ashe juniper tree, nectars on agarita blooms, Feb. 2019. Photo by Monika Maeckle

Known in Austin as “the Cedar Lady,” McGreevy taps more than two decades of contemplating Mountain Cedars to lay out their fascinating history and value.

For example, it holds great value for wildlife. The tree plays host plant to the Juniper hairstreak butterfly, Callophrys-gryneus pictured above. The endangered Golden cheeked warbler utilizes the shaggy bark of mature Mountain cedars to build its nests. Myriad mammals and 19 species of birds consume its blue, tangy berries. In the fall, we often see migrating monarch butterflies resting in the branches of Mountain Cedars along the Llano River. And in the winter, flocks of cedar waxwings crowd Mountain Cedars’ branches, gobbling up its berries.

In early 19th century Texas, Mountain Cedars were prized as a building material for cabins, telephone poles, and railroads and helped jump start the local economy. Mature Mountain Cedars contain high levels of wood oils that make the wood resistant to decay. As a result, the mature Ashe juniper forests that once comprised large swaths of the Texas Hill Country were clear-cut to harvest the bounty.

As cattle ranching took over in the 20th century, the land was overgrazed and the soil degraded, creating a fertile context for “pioneering cedar thickets,” the ubiquitous bushy, young Mountain Cedars that we see today.

After relaying the historical context and appreciation for Mountain Cedar, McGreevy then dispels the “tall tales” of the cedar myth.

For example, contrary to popular belief, Mountain Cedars are not an invasive species. The tree has been native to Texas for millenia. Juniper pollen was found in a cave in north central Bexar County and dated to be more than 10,000 years old. The Spanish in the 1700s and the Germans in the 1800s used Mountain Cedars to build their homes, missions, and barns.

A common sight in the Texas Hill Country during monarch migration season: the butterflies rest on Ashe juniper, a.k.a. Cedar. Photo by Monika Maeckle

McGreevy also makes the case that Mountain Cedars do not cause soil erosion. Natural forces like heat, rain, and chemical reactions cause erosion, she argues, not Ashe juniper. On the contrary, mixed forests of old-growth cedar and oaks work together to build soil and provide habitat. In the karst geology of the Hill Country, even the bushy pioneering thickets reduce erosion over time by reducing rain impact and shading degraded soil.

One of the most pervasive false claims about Mountain Cedars is that they are water hogs. That claim was based on a single, imperfect study conducted in 1996 by Dr. Keith Owens at McGreevy’s alma mater, Texas A&M University. The study claimed that the typical Mountain Cedar used 33 gallons of water per day while the typical oak tree averaged 19 gallons daily.

That study caused landowners and managers to believe Mountain Cedars suck more than their fair share of water from our aquifers. The media latched on to this claim and cast Mountain Cedars as horrendous water hogs.

Author Elizabeth McGreevy appreciates a log cabin in Kyle, Texas, built in 1850 with 16-foot cedar logs. Courtesy photo

Yet the study that was the origin of this claim proved extremely flawed, even according to its author, who admitted his methodology needed refinement and that “people just wanted a quick answer to explain our water shortages.”

Another study revealed that Mountain Cedars actually use only about six gallons of water per day and Texas Live Oaks consistently use more water than Mountain Cedars.

McGreevy tackles more than a dozen of these myths, then suggests several strategies for finding ways to “return the value to Mountain Cedars” to offset the costs of managing the species sustainably.

Cultivating Mountain Cedar wood oil and rosin, developing a market for bonsai cedars (which can go for $5,000 a piece), and using its wood as a building material are among McGreevy’s suggestions.

The book has earned kudos from several Hill Country conservation icons.

Bill Neiman, founder of Native American Seed in Junction, called it a “passionate, absolutely engrossing, 20-year compilation of work” that signals a paradigm shift. Retired national resources conservation specialist Steve Nelle labeled it a “game-changer for those willing to read it with an open and reasoned mind,” but cautioned “be prepared to have some sacred cows challenged.” And Frank Davis, Hill Country Conservancy chief conservation officer, said McGreevy’s book provides a “clear-eyed perspective” about the trees’ complex ecological role in the landscape.

“You have the urban people and the rural people, and they both get frustrated about Mountain Cedars,” McGreevy said by phone recently. Urban communities struggle with cedar fever and rural landowners are told by authorities they can get more soil, water, and grass if they clear the tree, which is a “never-ending process that doesn’t work,” she said.

“They get frustrated by the misinformation and answers that don’t work, and they direct the frustration at the tree,” she added. “I’m trying to get people to stop feeling hopeless about what can be done.”

TOP PHOTO: Slash and burn the cedar has been a classic land management strategy for decades. Photo by Monika Maeckle

Related posts:

- Pollen Trackers tap citizen scientists to monitor cedar pollen for allergy relief

- At war with Agave americana: tenacious plant resists chainsaw, digging, fire

- Trinity Students continue battle with Johnson Grass

- New study: nectar plants more important than milkweed for Monarch butterfly migration

- How to plan a successful pollinator garden

- Mostly native urban butterfly garden outperforms lawn every time

- IH-35 to Become Pollinator Corridor for Bees, Butterflies and other Pollinators

- Endangered Species Act: Wrong tool for the Job of Monarch butterfly Conservation?

- Texas Butterfly Ranch Native Texas Milkweed Guide

- A Year in the Life of a Mostly Native Urban Butterfly Garden

Like what you’re reading? Don’t miss a single post from the Texas Butterfly Ranch. Sign up for email delivery below, like us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter, or Instagram.

Oh, this is intriguing! I have never understood the juniper/cedar hatred. Look forward to reading this.

Thanks for the great review!! Look forward to reading it, especially after the great comments from Bill Neiman and others.

Oh the folly of turning a one-study result into a certainty! Keith Owens should have run his study again…

It’s good that the tree’s reputation is being rehabilitated.

Thanks for mentoring the monarchs.

Dr. Owens has continued his research. His original 1996 water use study was never meant to become gospel. If you read his abstract he clearly states he only looked at one Mountain Cedar and that he predicted water use would be extremely varied across the Hill Country. His follow-up research has shown just that! Turns out that high water use was more of an anomaly.

When we lived in the Hill Country, we loved our abundance of Ashe juniper. We loved the privacy, year round greenery, and watching all the birds who foraged and lived in the trees, not to mention the surprising grey fox or two. I was labeled a ‘tree hugger’ by our builder to explain to the subs why they weren’t allowed to take them down. (Darned straight I’m a tree hugger and proud of it.)

It is one of the worst times of year if you suffer from allergies to it. The states should consider using it in conservation rural settings and minimizing it in large suburban areas

People are allergic to Live Oak Pollen too but you do not see them ripping out chain saws for those like you do the cedar- Ashe Juniper. I find that amazing. I am letting my Juniperus ashei build soil, provide wind breaks, prevent erosion of soil, and I love making cool things with the posts. Such a useful, beneficial, beautiful tree. I have taken the dead limbs off of my mature cedars and they make such a stately, grand, large shade tree. I am proud of mine. Damn proud! Texas Proud! Yep, that’s me!

I am 100% with you!

I live in a typical Northside neighborhood and have actually transplanted baby cedars– one in my backyard and three in the front. Somehow, I lucked out with all females– so no one can accuse me of contributing to their cedar fever. I’m often on the prowl for cedar posts to use in landscaping the yard, so if you ever need any of yours thinned, I’d be happy to bring out the chainsaw.

I think they are beautiful trees!

Best book ever! I pre-ordered her book and love it! I really love FACTS, not BS even though those are my initials! Once you cut down a tree, cedar or otherwise, it is GONE. Think people!

Totally agree. I love them. Don’t understand why people want to cut out their privacy. I don’t think cutting down your trees will ever stop the cedar fever. They are beautiful to me.

Hi Netta, We love our privacy too and are blessed to have a Central Texas Hill County- Live Oak, Cedar Elm and Cedar forest for privacy. I will never remove it and consider it a blessing!!! By the way, some people say they are a fire hazard. The book sets that straight. It is only the dead or dehydrated ones that are. I was invited, as a Texas Master Naturalist to participate in a prescribed burn of 40 acres. I especially wanted to see what the fire did with the cedars. I can tell you, first hand, the fire just skipped over the live cedar trees. So much for that myth. That was one hot, smoky day! A great training and experience!!!

How do I get this book. I love these trees. Where I come from there are very few trees and I love these trees. I removed only the ones I had to for my house.

Click in the link in the story. —MM

It is available on Barnes and Noble web site and also on the Native American Seed web site. Incredible book!!!

I live in the Hill Country between San Marcos and Wimberly and we have many cedar trees on our place. I have cleared the ones within 30 feet around the house for fire safety because as we all know, they will burn very hot if they catch on fire. But mostly I leave them alone and if the cedar is close to my trails, then I will cut the lower branches so I can walk under them. Most of them are dead anyway, so it reduces the fire danger if presented with a grass fire. I believe there should be a harmony between the oaks and the cedars and nature has already given us the template for their coexistence. They live together in harmony and we should live in harmony with cedars. Can’t wait to read the book!

Hi Dan, I have read about the anti fungal properties of cedars and notice that many of my Live Oaks are growing with Cedars next to them, right beside them. There is a theory they may help with Oak Wilt! I hope you bought the book! I treasure my copy and give them as gifts to my clients, buyers of Texas land.

At the Lady Bird Johnson Wild Flower Center, it is taught that the Ashe Juniper was not found widely in central Texas before the farmers and ranchers showed up. Those people stopped the natural wildfires that formerly burned through the central part of the hill country. Those fires killed the Ashe Juniper, but the oak trees survived. The native grasses that grew here frequently were two to four feet tall and produced good soil, better soil than exists under these trees where not much of anything else can grow. Today’s landscape looks nothing like the one that existed before the European farmers arrived.

You can find yourself, if you search hard enough, multiple different accounts early throughout the early exploration (at least western exploration) documentation claiming “vast swathes of cedar (juniper)…” specifically around the plateau.

Like many teachers, some places like that simply teach “what is generally accepted.” It is what it is. But I specifically found multiple accountings. It took a WHILE to find. I think an hour or 2 on a google dive. And I am VERY good at finding random bits of info on the internet. One was a scanned version of an original copy. It’s only like 300 years ago. Documentation was around. XD. I would assume those accountings are some of the ones used in this book.

Elizabeth McGreey’s research is impressive and the conclusions are undeniable. Old growth cedar is worth saving for so many ecological and environmental reasons. My 27 years of pruning cedar and chipping the branches has finally been vindicated. I now have an old growth forest of over 11,000 tagged cedar trees with 5 miles of cedar mulch hiking trails. Thank you Elizabeth!

Sounds like heaven to me!

There has got to be a use for all the juniper trees covering Texas and oaklahoma. It’s doubtful they will go extinct, as prolific as they are. The only use I can think of is the berries for Gin. And there are millions of trees. Time for people smarter than me to find out.