Another uninvited plant has moved into our Texas landscapes. Unlike its edible cousin Bastard cabbage, this rambunctious invasive sports numerous stickery seed heads, a fleshy main stem, and is not tasty at all.

The aggressive invader: Malta Star Thistle, Centaurea melitensis. also known as Tocalote.

According to biologist and plant expert Kelly Lyons at Trinity University, the prickly annual is another import from the Mediterranean.

Malta star thistle sets down roots along the Llano River in the Texas Hill Country. –Photo by Monika Maeckle

“It’s inadvertently introduced by contaminated seed, often through seed mixes from the west coast,” said Lyons, who has been studying native and invasive plants for decades.

“This is not a new story….It’s just part of a larger trend of Mediterranean annuals being introduced and succeeding in response to climate change. And we need to stop it.”

We’ve been combatting this interloper at our family ranch on the Llano River for several years, but this year’s cool, wet spring has made for an uphill fight.

Tocalote’s thorny, fleshy rosette is among the first to emerge in spring, responding well to cool temperatures and decent rains. Like other early arrivals, it hogs the sunlight, water and soil, and crowds out native wildflowers like bluebonnets and verbenas.

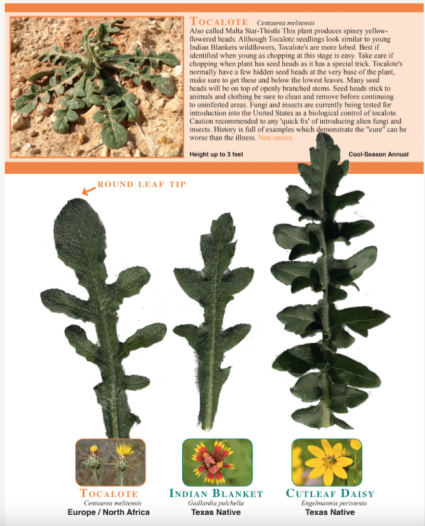

Malta star thistle masquerades as native wildflower rosettes in the spring, and is often mistaken for Indian Blanket and Cutleaf Daisy. –Graphic via Native American Seed

For better or worse, its early rosette resembles those of native wildflowers like Indian Blanket and Cutleaf daisy. This helps it disguise itself as we comb our landscapes for undesirables, allowing the aggressive thistle to get established. Native American Seed Co. has a useful handout that shows the similarities.

At our ranch, it appears congregated mostly along our roads, apparently a hitchhiker on tires and undercarriages via its annoying adhesive stickerburr seeds. Birds also consume the seeds and can disperse them via their scat.

This undesirable thistle is not restricted to the Hill Country. Texans will find it elsewhere in the state and it seems to be concentrated in areas where it was unintentionally imported according to the Texas Invasives Species map.

The winter annual/sometime biennial can reach two feet in height. Its simple taproot can be a challenge to pull, especially in dry soils. Fleshy leaves emerge from a basal rosette and each stem can produce a prickly seed head that erupts into a tiny yellow flower–as many as 60 or more seeds per head and 100 heads per plant.

Malta star thistle also has an ingenious reproductive trick: even if you weed whack or clip it to the ground and rake up the foliage, the stem base hosts a basal seed head, which when left intact can fuel future growth. When clearing Malta star thistle, be mindful to make a sweep of the these solitary, hidden seed heads and flowers. Bag them up and put them in the trash. Or dry them out and burn them.

Brilliant, but it doesn’t belong here. Even though we cut the stems to the ground, Malta star thistle hides a lonely flowering head with seeds for future reproduction. –Photo by Monika Maeckle

Unlike us, our neighbors in the Mason, Texas, community got a jump on the feisty annual early in the spring when they first emerged.

“I had an invasion after bringing in some gravel, and pulled all the plants before they seeded,” biologist and author David Hillis said in a recent Facebook post. “That was five years ago. I have not had any more come back since. It is a lot of work, but pulling the plants before they seed is the only way I know to stop them.”

Mason resident Tony Plutino agreed.

Wear gloves when pulling Malta star thistle. The sticker riddled seed heads hurt. –Photo by Monika Maeckle

“I pull them and cut them (before a seed head forms), then encourage natives in hopes of leaving less space for the Malta star thistle,” said the Texas Master Naturalist and proprietor of Llano River Region Adventures. Plutino said moist soil helps with pulling.

“It is a lot of effort, but it works….It’s an endless task.”

Just be sure to wear gloves when pulling this plant. The stickery seed heads are painful.

Kelly Lyons, Robert Rivard and Lars Anderson team up to weed-whack, then bag and burn Malta star thistle plants along the Llano River. Tim Riggins, canine supervisor, oversees the effort. –Photo by Monika Maeckle

The U.S. Department of Agriculture suggests mechanical and chemical strategies for eliminating Malta star thistle in a field guide specifically devoted to its management. The approaches take years, given that the seeds can survive for a decade in the soil.

Noting the features that make Tocalote such a successful invader, the guide points out its “deep taproot that accesses available soil moisture, winged stems that dissipate heat, and formidable spines at maturity that deter grazing by livestock or wildlife.”

The USDA suggests that most attempts to manage Malta star thistle require “a long-term commitment of greater than three years” to deplete the seed bank.”

TOP PHOTO: Malta star thistle is riddled with sticker covered seed heads that hitch rides on tires, clothing and animals. – Photo by Monika Maeckle

Related posts:

- Bastard Cabbage, a rambunctious and tasty invasive, is ousting our native Texas wildflowers

- Scientist and naturalist David Hillis provides holistic and enlightening tour of the Texas Hill Country

- Monarch butterflies heading our way as wildflower bounty awaits

- No monarchs yet, but Red Admirals fluttering through Texas

- Clammyweed named 2024 Pollinator Plant of the Year

- Pollinatives, San Antonio’s second native plant nursery, results from couple’s retirement “deal”

- Mostly native urban pollinator garden outperforms lawn every time

- Flower “bed” works overtime as bachelor pad for solitary bees

Like what you’re reading? Don’t miss a single article from the Texas Butterfly Ranch. Sign up for email delivery at the bottom of this page, like us on Facebook, follow us on Twitter, @monikam or on Instagram.

Monika – The problem is exacerbated in my 1 acre minimum suburban neighborhood near Dripping Springs – maintenance services bring the thistle in on equipment and spread it everywhere! And the county mows the roadsides at least once/year. I monitor and hand weed alongside my road to prevent it from spreading onto my property. Just grabbed a bunch on today’s walk!

Meg