Monarch butterflies are making their way north, launching the 2025 spring migration season.

Journey North, a nonprofit conservation organization that tracks the monarch and other migrations, noted in its weekly newsletter that monarchs had been sighted in Houston, Galveston, Montgomery, and other Texas locations. Here in San Antonio, I’ve only seen a single monarch so far this season.

Conditions in Texas, often the insects’ first stop for laying eggs on milkweeds and fueling up with nectar, do not look advantageous.

The pollinator garden in front of the San Antonio River Authority had little to offer pollinators this week. –Photo by Monika Maeckle

A multiday freeze that included sequential nights in the 20s in February stunted many forbes that mistook previous warm spells for springtime. This last week had temperatures climbing into the 90s, resulting in weather whiplash that proves challenging for plants, wildlife–even people.

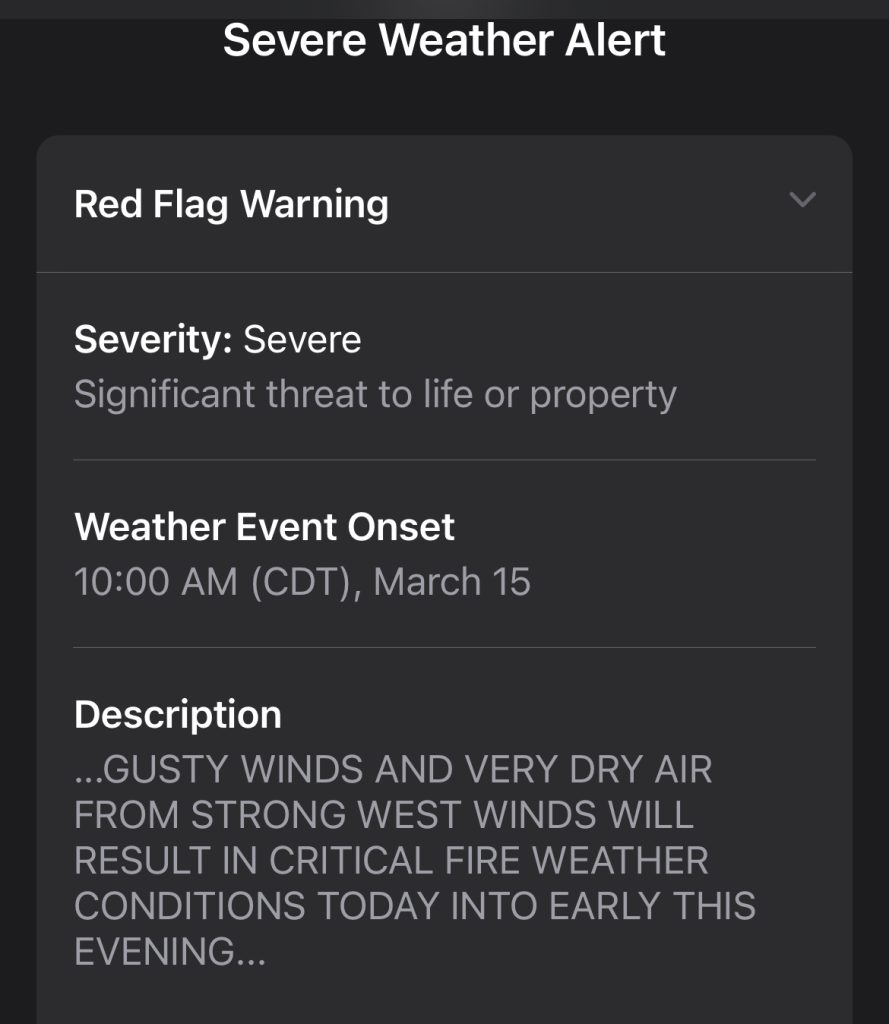

Meanwhile, drought persists through much of the state and continues to hinder spring growth. Severe winds, and resulting tornadoes, wildfires and storms hardly afford a hospitable stopover for the insects, which have endured a long winter and are now in reproductive mode.

Here in San Antonio, we just moved from “extreme drought” to “exceptional drought” according to the National Drought Mitigation Center. So far this year, we’ve received a scant 1.77 inches of rain, and only 5.99 inches since last August–which is more than 13 inches below what is typical for that six-month period, according to a recent article in the San Antonio Express-News.

While the recent announcement of a 99% increase in migratory monarchs in Mexico over last year was heartening, general pollinator tidings have been dreary.

A study published March 6 in the journal Science announced a dramatic decline overall for butterflies in the first two decades of the 21st century.

Tapping 35 different citizen science programs across the U.S., researchers found that two-thirds of species reviewed declined more than 10% in the last 20 years. Overall butterfly abundance fell 22% across 554 recorded species.

Weather alerts delivered by phone have been routine lately.

David Wagner, entomologist, author of Caterpillars of Eastern North America and professor at the University of Connecticut, labeled the study’s findings “catastrophic” in an interview with the Washington Post.

Read a summary of the study here.

Interestingly, monarch butterflies were NOT one of the butterfly species in decline, according to the Science study.

As migration studies expert Andy Davis noted on his Thoughtful Monarch Facebook page, most of the butterflies in serious decline were smaller species with limited breeding ranges.

“Looking through this list, I see a lot of skippers, and otherwise really small butterflies. Not sure why that is,” he wrote in one post.

Davis dug into the data and shared with followers that “the analyses of all of the monarch counts from across the breeding range showed… NOTHING. There was no statistical decline, no statistical increase. In other words, the monarch numbers in the last 20 years have been stable.”

Davis has famously argued, as I point out in my book, The Monarch Butterfly Migration Its Rise and Fall, that the breeding population of monarchs is doing very well, thank you, and that the monarch migration is at risk (not monarch butterflies) because migrations are hard. Other scientists have joined him in this viewpoint.

“Monarchs do not really need our help, they just need to be left alone,” Davis told me.

Antelope horns milkweed, Asclepias asperula, appears to be late and stunted this year, but moanrchs are finding it. –Photo by Monika Maeckle

Meanwhile, the petition to list monarch butterflies as “threatened” under the Endangered Species Act closed for comments on March 12.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service now has the rest of the year to determine and inform the public what the final rules and consequences of the listing will be. The petition had more than 68,000 comments when it closed at midnight this week.

As for this year’s migration, it seems to be taking flight in a more challenging environment than usual.

“Nothing yet,” said Don Gray, a Master Naturalist in Mason, Texas, when asked if he’d seen any monarch butterflies yet. “They’d be hard pressed to find a bite to eat around here.”

Chuck Patterson of Driftwood, Texas, a frequent contributor to the Monarch Watch email list known as the DPLEX, reported that on a recent morning walk, he noticed a consistent theme: milkweed is limited and mostly small in size.

Patterson said he observed a few “larger stem plants and a few that even had buds developing. On a positive note I did see the first emergence of prairie verbena, but only a few were seen.”

He added that he hadn’t seen any monarchs but that he spotted 30 eggs across 3 different areas–all on Antelope Horns milkweed, Asclepias asperula, the South Texas commoner.

A recent walk along the San Antonio River revealed little blooming and lots of dead growth awaiting clean-up, rain, and spring renewal.

TOP PHOTO: Faded monarch butterfly on Antelope Horns milkweed in March of 2021. –File photo by Lee Marlowe

Related articles

- Monarch numbers in Mexico vault 99% over last year’s near historic low, California population teetering

- Commercial butterfly breeders brace for devastating hit as monarch ESA listing looms

- Monarch butterflies listed as “threatened” under the Endangered Species Act

- A tense online debate: raising monarch butterflies at home

- New study: monarch migration at risk, monarch butterflies are not

- USFWS rules monarch butterflies worthy of protection, but they don’t have resources to protect it

- As ESA listing looms, new study challenges dogmatic narrative that monarchs are in decline,

- “Weird” weather has scientists concerned about this year’s monarch butterfly migration.

That’s why I am a TRUE Butterfly 🦋 LOVER! It just amazes me the resiliencey of these seemingly “fragile” creatures. They seem to be able to coexist even in our drought times and they bring us such an abundance of beauty as well as, WELLNESS !🧚♀️