One could compare the recent US Fish and Wildlife Service decision on the state of monarch butterflies to a hospital overwhelmed with COVID-19 patients. Too many sick people and not enough staff/beds/ventilators to treat them. The neediest cases prevail, and some patients return home sick–or never even enter the emergency room.

In a case of conservation triage yesterday, US Fish and Wildlife Service relegated monarchs to the emergency room, determining after six years of consideration that the species can get in line behind 161 others awaiting protection.

The official ruling, “warranted but precluded, ” means the butterfly moves into a queue as an official candidate for listing under the Endangered Species Act. It does not, however, begin regulatory initiatives because the agency has “higher priority listing actions,” according to USFWS. Instead, the monarch’s status will be reevaluated annually.

Monarch butterflies need nectar plants like the daisy species above (left) and host plants on which to lay their eggs such as Antelope horns milkweed (right). Photo by Monika Maeckle

The ruling came down after more than six years of consideration that resulted in a broad range of public conservation efforts by nonprofit, government agencies, NGOS and individuals to assist the iconic species. Those collective efforts have resulted in more than 500 million milkweed stems (the monarch butterfly’s host plant) and 5.6 million acres of pollinator habitat planted to date, according to USFWS officials.

In August of 2014, the Xerces Society, Center for Food Safety, Center for Biological Diversity and Dr. Lincoln Brower submitted a petition to the Secretary of the Interior requesting the monarch butterfly be listed as “threatened” under the ESA. In December of 2014, USFWS published a 90-day finding that listing the monarch might be warranted, and initiated a status review of the species. The Service then failed to rule on the petition by the statutory 12-month deadline. A lawsuit ensued, and by 2016, USFWS received a three-year extension. Last year, USFWS received another extension, and December 15, 2020, was set as a deadline.

The decision effects the monarchs’ two distinct populations.

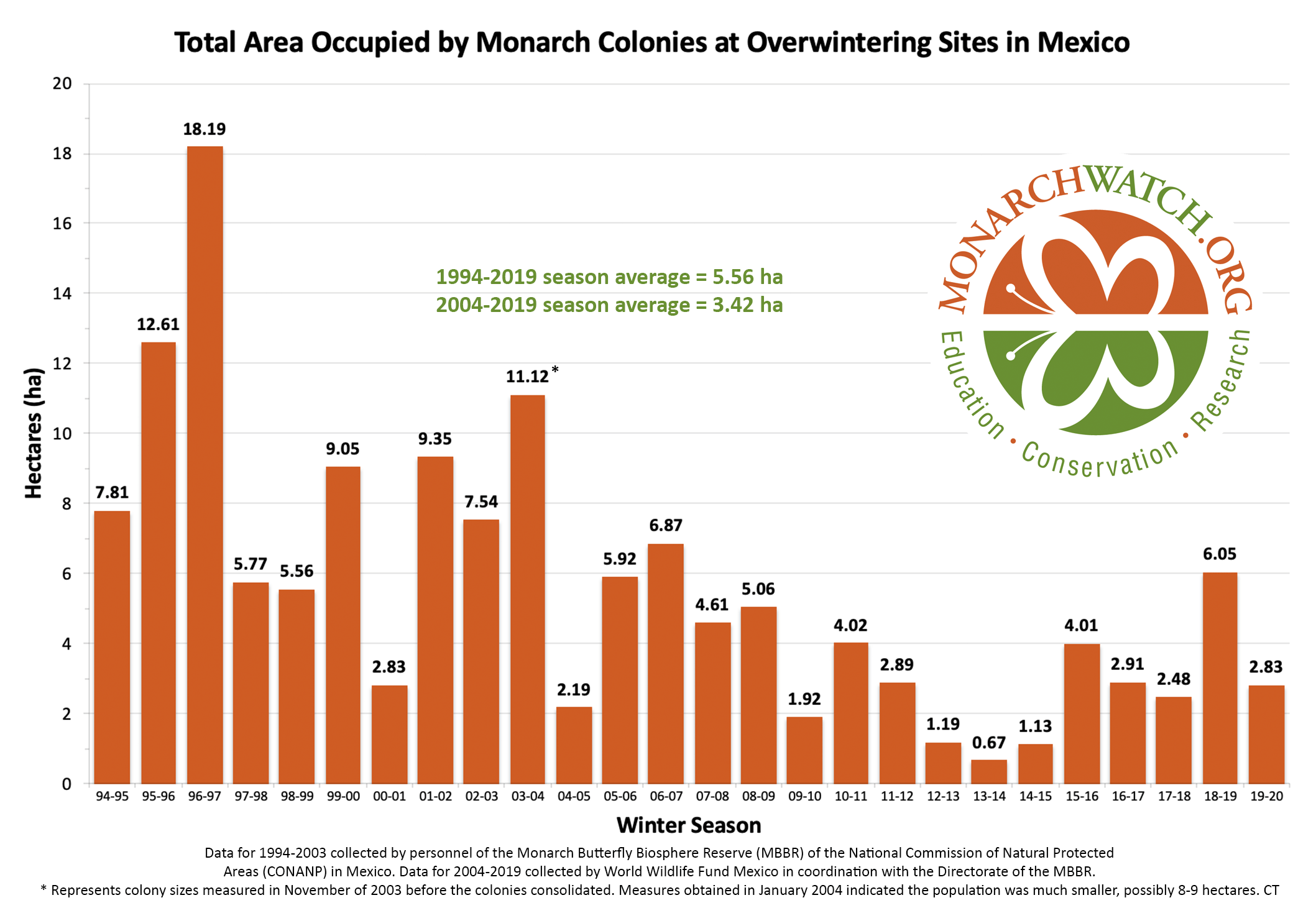

The eastern monarch population, which migrates from Mexico to Canada and back to Mexico, is much larger and fluctuates annually, numbering in the tens of millions. The butterflies migrate south to overwinter in a small area of high altitude mountains west of Mexico City each fall.

According to USFWS, monarch numbers in the eastern population fell from an estimated 384 million in 1996 (occupying 45 acres) to fewer than 60 million (about 7.5 acres) in 2019. Both years represent boosts from the historic low in 2013 of 14 million monarchs.

“It is never good news when we find that listing an animal or plant is warranted,” said Tim Petronski, assistant regional director of external affairs at US Fish and Wildlife Service, at a press conference. “It means tough challenges ahead.”

Petronski lauded the efforts of monarch conservationist organizations, NGOs, volunteers and citizen scientists, stating that such efforts have made a big difference. “That means we have the time to work on listing actions that are a higher priority while we keep our foot on the gas with monarch conservation,” he said.

The much smaller western population, which moves up and down the California coast, has seen dismal numbers in recent years as a result of wildfires, climate change, habitat destruction, and pesticide use.

The Xerces Society, a pollinator conservation organization and one of the parties that filed the original ESA petition, announced earlier this month via their Western Monarch Thanksgiving Count that the western migratory population is headed for an all-time low. With approximately 95% of the data in, only 1,800 monarchs had been reported. In 1981, more than one million of the iconic orange and black insects were counted overwintering in eucalyptus trees along the Pacific coast.

Reactions to the news in monarch conservation circles was mixed.

“The warranted but precluded decision for monarchs is the right one at this time,” said Chip Taylor, founder of Monarch Watch, which tracks the butterflies’ migration through a citizen science tagging program. “It acknowledges the need for continued vigilance due to the numerous threats to the population while emphasizing the need to continue support for programs that create and sustain habitats for monarchs.”

Karen Oberhauser, founder of Monarch Joint Venture, another citizen science organization devoted to monarchs, and who now serves as director of the University of Wisconsin at Madison Arboretum, expressed measured disappointment in a blog post on the Arboretum’s website.

“If we agree that preserving this amazing species for our children and grandchildren is a worthwhile goal…we must run faster. The protection of the Endangered Species Act would have helped us do that,” wrote Oberhauser.

Beryl Armstrong, a partner in Austin-based Plateau Land and Wildlife Management, categorized the listing as “kicking the can down the road.”

“Basically they’re saying, ‘Yes, the monarch is eligible but we have another 161 species in line, and when you get to your turn, we’ll list you,” said Armstrong, who has worked with private landowners on conservation of rare and endangered species for decades

In San Antonio, the nation’s first Monarch Butterfly Champion City, Laurie Brown, organizer of the Alamo Area Monarch Collaborative and director at Cibolo Center for Conservation, said “It’s not the best outcome, but it’s not the worst,” said Brown.

“I am supportive that the US Fish and Wildlife Services will reevaluate the monarch status each year. This will keep the monarch and other species that are supported by the same ecosystem in the much needed limelight for conservation.”

The collaborative represents a group of local nonprofits and individuals who work to help the City of San Antonio make good on monarch conservation action items to which it committed for the National Wildlife Federation’s (NWF) Mayor’s Monarch Pledge. Mayor Ivy Taylor signed in 2015 and Mayor Nirenberg renewed the Pledge in 2017.

The NWF’s monarch outreach coordinator Rebeca Quiñonez Piñón pointed out how unfortunate it is that so many species are waiting in line for protection under the Endangered Species Act. “This is an opportunity to reflect on the long list of species that desperately wait to be protected under the Endangered Species Act. It is time for all Americans to adopt a culture to protect and conserve before it is too late.” she said.

TOP PHOTO: Monarch butterfly nectars on Gregg’s purple mistflower. Photo by Lee Marlowe.

Related articles

- AS ESA listing looms, new study challenges dogmatic narrative that monarchs are in decline,

- Q&A: Migration expert Andy Davis says for monarchs it’s survival of the biggest

- Happy 50th Earth Day: Monarch butterflies enjoy a win of sorts

- Endangered Species Act: wrong tool for monarch butterfly conservation?

- USFWS gets three more years to evaluate monarch butterfly ESA status

- Founder of the monarch butterfly roosting sites lives a quiet life in Austin, Texas

- Entry to Mexico’s most popular monarch butterfly preserve should cost more than $2.77

- How to plan a successful butterfly garden

- What will happen to pollinator advocacy under President Donald Trump?

Im doing my part, collected 1000’s of milkweed seeds, have a bunch of Monarchs flying around right now and thats after a 32 degree night last night Dec 17 2020 Houston

Thank you for this excellent summary of the history, process, and reaction to the petition. I shared it on my page.

I found a monarch with a broken wing sitting by my pool. Can I take him in and make him a home or is there no way to save him?