It took guts to start a glossy, full color print journal dedicated to the niche topic of pollinators. Print magazines, newspapers and journals, like bees, bats and butterfies, are in steep decline. But that didn’t discourage Kirsten Traynor, an English major turned PhD in bee science, from launching what was recently hailed as the “Vanity Fair of pollinator magazines.”

The honey bee biologist created a Kickstarter program On November 12, 2019 to raise $10,000 to fund 2 Million Blossoms, a quarterly journal dedicated to educating people about pollinators. By December 12, the campaign had raised $21,492 from 273 backers.

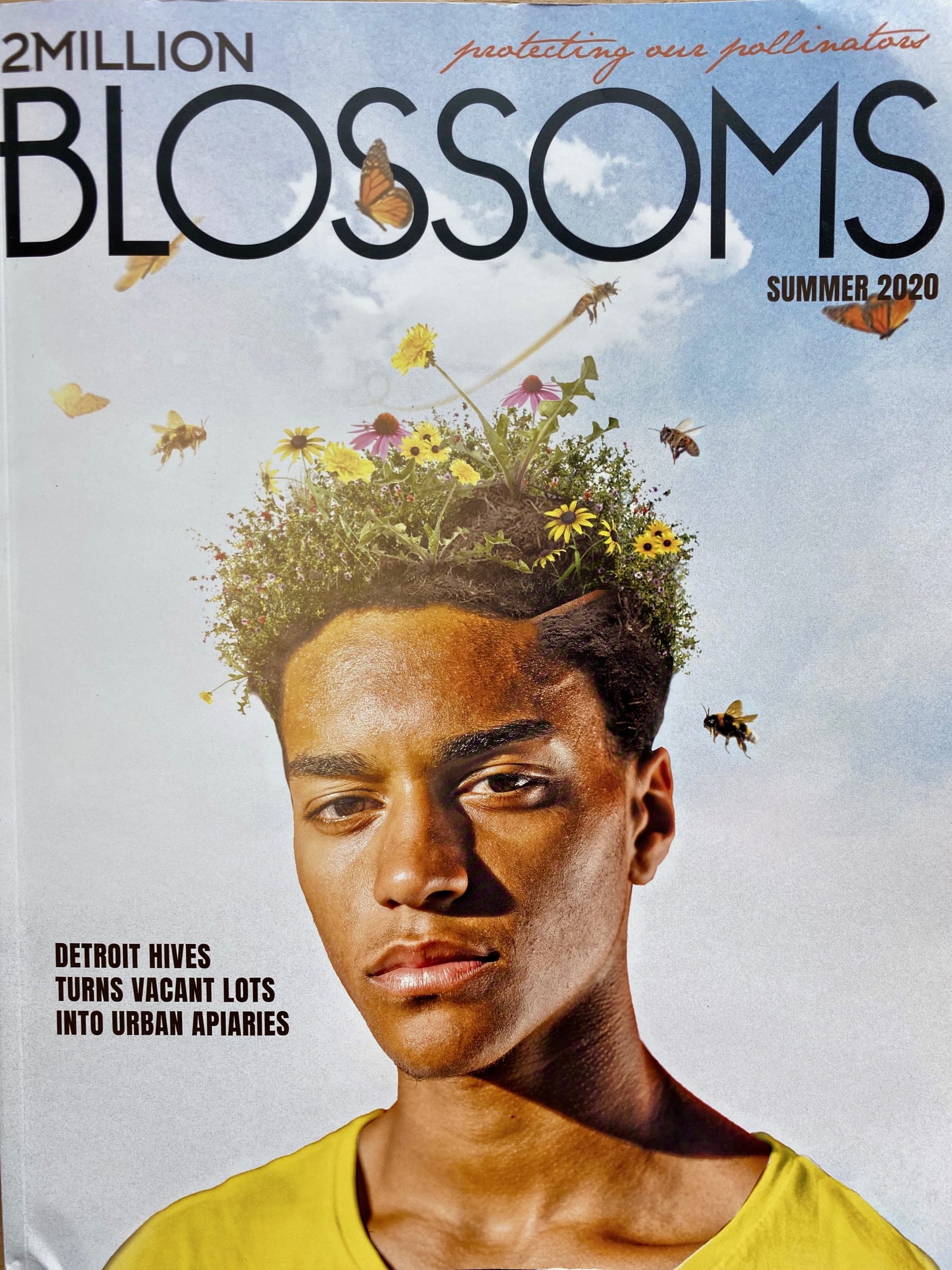

The current issue, Traynor’s third, numbers 104 pages and includes lush color photography, more than 20 long and short form articles, and advertising support from myriad beekeeping suppliers, nonprofits and magazines, as well as a seed company.

The magazine, and Traynor, emphasize honey bees, but features other pollinators like native bees, hover flies, butterflies and wasps, and stories on pollinator gardening and pollinator drone technology. The June 2020 issue includes two articles I wrote–one on the history of monarch tagging, and the other on how to tag a monarch butterfly.

Check out a free sample of 2 Million Blossoms here.

Traynor’s path to 2 Million Blossoms includes as many pivots and flits as a bee in a wildflower patch.

After studying English and creative writing, she worked at a 23-acre farm in Maryland as a steward of woodlands, crops and streams. She planted a wildflower meadow and took a beekeeping class. She entered the class raffle for a bee hive and won–“not the bees, just the box,” she said.

Like many before her and since, Traynor fell in love with beekeeping–and has never looked back.

She earned her PhD in bee biology at Arizona State University in 2014. Currently, she splits her time as a research fellow at both the University of Arizona and the Free University of Berlin, where she is investigating how pesticides and other stress factors impact the social dynamics of bee colonies.

When she’s not out in the field conducting hive checks or bee surveys, or at her desk editing photos and copy, Traynor likes to kayak, swim, “do anything in the water….I’m a water rat,” she said. She also likes to hang out with her cat, Galveston.

We caught up with Traynor in Germany, where she is spending her summer conducting research. Here’s what she had to say.

1. What moved you to launch a hard copy journal about pollinators this year, and how is that going with funding and subscribers?

Traynor: I love beautiful books and magazines. Although I read a lot electronically there is something deeply satisfying about holding an elegant, vibrant publication in your hand. I love the serendipity of paging through and discovering an article that makes you pause because it catches your eye.

I previously edited both Bee World, published by the International Bee Research Association, and American Bee Journal, which has been printed since 1861. Both have a fascinating history and dedicated readers, but neither one captured what I wanted to create. My goal with 2 Million Blossoms: protecting our pollinators is to inspire, inform and entertain. Good storytelling causes us to care. And when we start to care, we’re more willing to change our habits and share our spaces.

The idea for the magazine was born in late 2018, when I resigned from American Bee Journal. At the time I was based in Berlin, Germany, on a fellowship. This German city is incredibly rich in urban pollinator habitats. At the same time, I saw that there was a growing divide in the media pitting beekeepers against native bee enthusiasts.

Yes, too many honey bee hives in areas of low resources can put pressure on the native bees trying to hang on. The honey bee is native to Europe and in Berlin it thrives in the city, as do over 300+ species of other bees. Regardless of our favorite pollinator, many of our goals align—improved habitat, less fragmentation of what remains, reduced pesticide use, more emphasis on insect declines, increased research to understand how climate change is driving loss of biodiversity.

Kirsten Traynor in her beekeeping element. Courtesy photo

2. Has COVID-19 effected your efforts?

Traynor: Yes, unfortunately it has. All of my speaking engagements in the United States and abroad were cancelled. Also to help get the word out, I often send clubs informational postcards and a magazine subscription as a door prize. None of these clubs are meeting in person, which means we’ve had to get creative with letting people know about the magazine. I’ve hired a paid media marketing intern, who is developing our online presence on Instagram, Twitter and Facebook.

I’ve started doing Zoom talks and Facebook Live Events. Our next one is July 19th at 6 pm EST. We’ve been reaching out to garden groups and pollinator associations to let them know we exist.

3. What do you consider the single most pervasive cause of pollinator decline?

Traynor: Loss of habitat. We plow under an obscene amount of land daily. According to the US Forest Service, we lost approximately 34 million acres of open space between 1982 and 2001. That’s four acres per minute and 6,000 acres per day. When we destroy habitat, it makes it harder for pollinators to move and migrate, their ranges shrink, they have a harder time finding mates and reproducing. Pollinators are dependent on nectar and pollen. Yet we’ve plowed under, paved over, and drastically changed the landscape, making it harder for the insects and animals that feed us to find food for themselves.

4. You’ve spent a lot of time studying bees and other pollinators in Europe. How does the European approach to pollinator decline differ from ours the U.S.?

Traynor: That’s a tough question to answer succinctly. Europe in general tends to follow the precautionary principle, seeking to make sure something is truly safe before allowing its widespread use. In the United States, we often leave the testing of pesticide risk up to the makers and only when we find widespread harm, do we pull it. There’s an excellent study that came out in June 2019 demonstrating that the US lags behind Europe, Brazil and China in banning harmful pesticides.

Most of Western Europe firmly believes in climate change science and is working hard to minimize its impact. The EU also funds a great deal of pollinator projects and biomonitoring of species decline. The government works closely with NGOs and cities to enhance habitat in urban areas. Berlin is an excellent example, where the Deutsche Wildtier Stiftung (German Wildlife Foundation) has developed numerous meadows in city parks, planting pollinator rich habitat.

Traynor and her favorite feline, Galveston. Courtesy photo

We were making headway in the United States with the Pollinator Protection Act, but it seems that the current administration is trying to roll back quite a bit of it. Chlorpyrifos was supposed to be banned, but when Scott Pruitt was head of the EPA, he reversed the 2015 Obama decision to ban this harmful pesticide.

5. You’ve said that 2 Million Blossoms hopes to spark dialogue between sides that often are at odds. How do you bridge the gap between native pollinator enthusiasts and European honeybees?

Traynor: I think we need to live in balance. Honey bees serve an important function in modern day agriculture. They are the pollinator work horses that can be brought in to pollinate large mono crops. With up to 50,000 individuals in a colony, they’re hard to top in their sheer numbers. Solitary bees are often individually more efficient pollinators. We have different pollination needs throughout the world and it’s foolish to think that one species can serve all our needs. Some studies have now shown that honey bees and solitary bees function like a complementary insurance policy, with each species focusing on different parts of the tree. Our bumble bees and carpenter bees have a larger thermal mass, and so they can pollinate on those cool, windy spring days. We need them all. In threatened habitats where a few rare native pollinators cling on, we don’t need to add pressure from large numbers of honey bees.

The best way to bridge the gap is to provide more habitat and food sources for all. In Europe and Asia, honey bees and other bees lived and thrived together. They only compete in certain areas because we’ve removed so many of the flowers they depend on.

6. Anything else you’d like to add?

Traynor: If you love pollinators, check out my first issue available for free online. With every new issue we always put some content online for people to read for free. If you like it, please consider subscribing. Your subscription goes a long way, helping us fund future issues, so we can keep creating excellent content for our readers. I currently produce this magazine without any compensation, editing, designing and doing the layout myself. All funds go towards my writers, cover artists, and production costs. So if you want more great content, consider purchasing a subscription or gifting one to a friend. Many readers tell me the magazine is the only thing they read cover to cover.

TOP PHOTO: Kirsten Traylor poses with a field of wildflowers. Courtesy photo

More articles like this:

- Q & A : Migration expert Andy Davis says when it comes to monarchs “it’s survival of the biggest”:

- Q & A: Dr. Lincoln Brower talks ethics, endangered species and milkweed and monarchs

- Q & A: Dr. Anurag Agrawal challenges Monarch butterfly conservation conventional wisdom

- Q & A Journey North’s Elizabeth Howard talks tech, citizen science and mass butterfly releases

- Monarch butterflies head our way as big wildflower bloom awaits

- Cowpen Daisy named San Antonio’s “unofficial” pollinator plant of the year

Like what you’re reading? Don’t miss a single article from the Texas Butterfly Ranch. Sign up for email delivery at the bottom of this page, like us on Facebook, follow us on Twitter, @monikam or on Instagram.

It seems ecologically irresponsible, and waste of money, to launch a paper magazine now when the same results could be obtained with an online only version. What was the thinking behind this?

I have to admit I have been having the same thought as Ignatz. It takes a great deal of money to print magazines, and of course, a great deal of paper. Plus the carbon footprint involved with physically delivering the magazine. Though one can use recycled rather than glossy paper, and there are ecologically friendly inks – why? I actually prefer a pdf version, much easier to file away for future reference.

I do like the topic of pollinators, and I hope this succeeds in a digital format.

Can u help…looking for milkweed for Monarchs….

in the woods where I live outside Myrtle Beach. It seems there is a huge similarity between Sweet bay magnolia leaf and what a knowledgeable person found and identified as milkweed. How do I tell the difference? Thanks T