Storm Uri gripped Texas for 151 continuous freezing hours in February and took a major toll on Texas wildlife. Birds, exotic game, armadillos, myriad fish, bats and other creatures perished in the Texas freeze of 2021.

Plants suffered, too. Some parts of Texas experienced 90-degree temperatures earlier in February and the hot spell provoked premature new growth a month before the traditional average last frost date of March 15. Then the freeze hit, stopping plants in their tracks.

It remains to be seen how the monarch butterfly migration will fare. A reduced population of the iconic butterflies has already begun their journey north.

Nueva St. dam pollinator garden with Tropical milkweed on the San Antonio River on February 4, 2021. Photo by Monika Maeckle

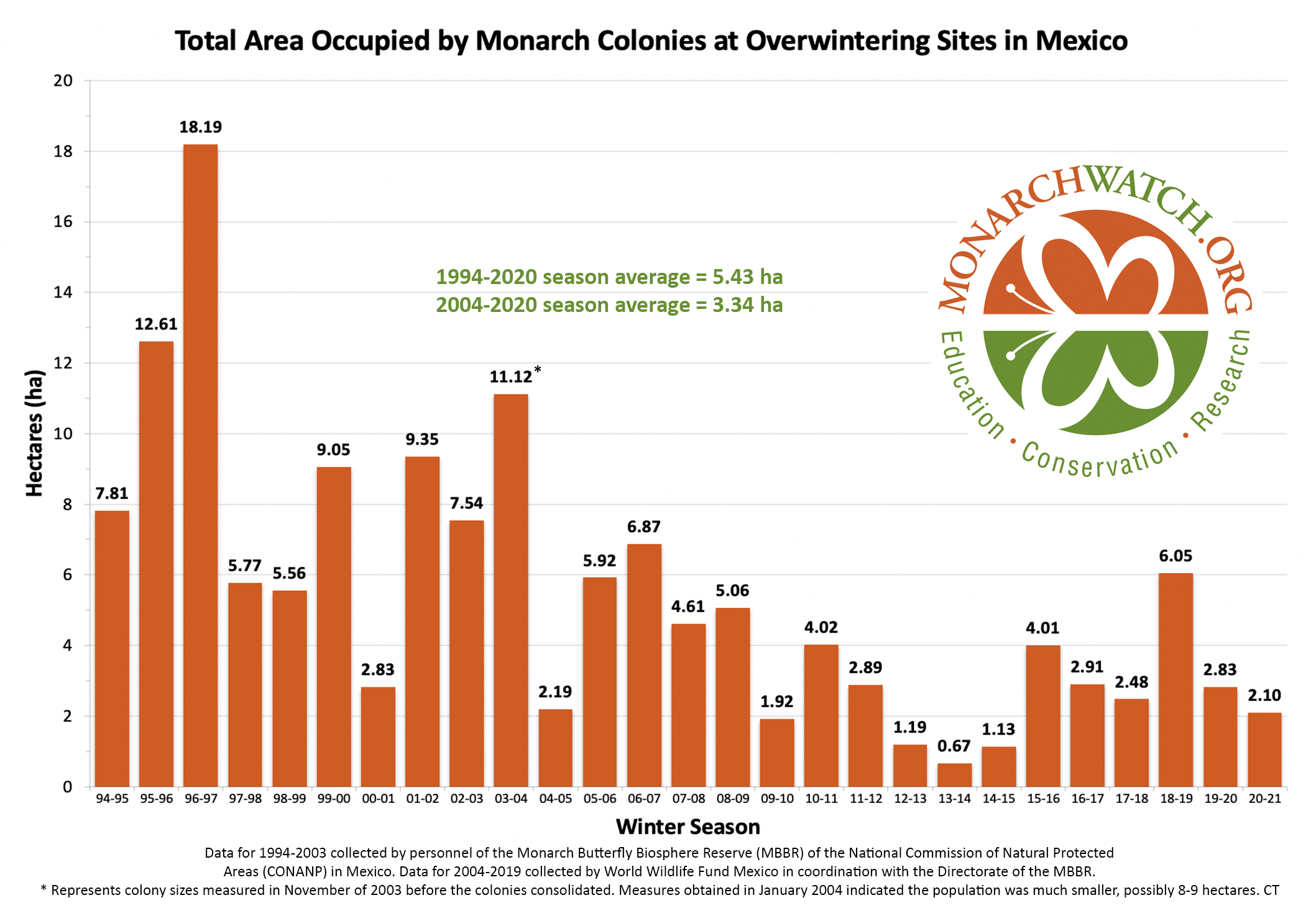

The number of this year’s overwintering monarchs dropped 26% from last year, World Wildlife Fund officials announced last week. All the migrating monarch butterflies east of the Rocky Mountains, which pass through Texas during their spring and fall migrations, occupied only 2.1 hectares of forest at the Mexican overwintering sites. That’s about five acres of butterflies, down from 2.83 hectares, or about seven acres, reported last year.

Officials attributed the decline to forest degradation at the roosting sites, habitat loss, and climate change.

“During the spring and summer of 2020, the climatic variations in the southern United States were not favorable for the flowering of milkweed and the development of eggs and larvae,” WWF stated in a February 25 press release.

Those unfavorable conditions will be amplified in the wake of the historic Texas freeze.

Few flowering nectar plants exist at the moment and milkweeds–native and nonnative–appear to have stalled in some areas of the Texas Funnel, the area where monarchs typically lay the first generation of eggs in the their multi generation migration.

John Barr of Native Cottage Gardens said in a post to the DPLEX list, an email list devoted to monarch butterfly scientists, citizen scientists and enthusiasts, that he went to look for milkweed this weekend on a roadside in west Austin that he’s monitored for years.

“I was unable to find any sprouts of native milkweed,” he wrote.

Barr returned the following day, “looked again, and added a second location….I still found no milkweed.”

Further south, Catherine McReight saw mixed milkweed results.

“Prior to the big freeze here in Houston, Texas, my Asclepias Oenotheroides (Zizotes milkweed) was emerging quite nicely….Obviously, the fresh stems died as a result of the freeze,” she noted on the listserv, adding that other species were just starting to emerge.

But Mike Quinn of Austin posted a photo of Asclepias asperula, Antelope horns milkweed, sprouting in San Marcos, Texas, on March 2.

Storm Uri took out large stands of the much debated and widely available Tropical milkweed, Asclepias curassavica, in San Antonio.

Butterfly gardens along the San Antonio River planted by the City and the San Antonio River Authority were frozen to a crisp, the Tropical milkweed and other species largely decimated.

Nueva St. dam pollinator garden with Tropical milkweed on the San Antonio River on February 18, 2021. Photo by Monika Maeckle

“It’s going to be a 50/50 chance of regrowth on the Tropical milkweed,” said Juan Guerra, senior horticulturist for the City of San Antonio. “Some of the stuff on the River Walk is starting to re-sprout but only time will tell. We are planning to add some Tropical milkweed as soon as they become available, as well as native milkweed,” he said.

Adding to the usual challenges of the migration, the butterflies appear to be leaving their roosts earlier than usual.

Ellen Sharp, who lives near the sanctuaries and runs JM’s Butterfly BnB with her partner Joel Moreno in Macheros, Mexico, filed the following report for Journey North on February 24.

“And now they have already begun their long, staggered departure. It’s early, you say, can’t you tell the butterflies to wait? What with the deep freeze that’s hit their nectar and milkweed sources smack dab in the middle of their Texas flyway, it’s a terrible time to start flying north again,” Sharp wrote.

“The monarchs seem to be responding to some other logic, and we can only hope that it’s one informed by a wisdom beyond our perception, and not just more evidence of a climate that’s lethally out of whack with most of Earth’s creatures (which is probably how many Texans are feeling about it these days).”

Hena Cuevas, a filmmaker from Bader Content Studios in Washington, D.C., mentioned in a recent phone call that her documentary filmmaking team had planned to visit the monarch butterfly roosting sites for a film shoot the second week in March. “But when we called in February to confirm, they told us, ‘you better get down here…they’ll be gone by then.'”

Timing matters for the monarch butterfly migration. The butterflies typically leave Mexico when temperatures climb and days get longer. Warmer weather makes them burn through their stored fats and pushes them to reproduce, taking their last gasp at life to continue the life cycle.

After breeding, female monarchs start moving north in search of milkweed, the only plant on which they’ll lay their eggs. But if no milkweed exists, they’ll keep flying. Or die without reproducing.

Monarch Waystation and pollinator garden in downtown San Antonio on March 2, 2021. Photo by Monika Maeckle

“Momma monarchs have to lay most of their eggs in Texas in March and the first week of April for the population to start well,” Chip Taylor, founder of Monarch Watch, the citizen science tagging organization operated by the University of Kansas at Lawrence, added to the DPLEX discussion. “We need Willie or Waylon to sing them a song to that effect as they evade the border patrol near Brownsville in the east and Del Rio in the west.”

For Texas residents, this year’s freeze spawned a round of dejavu.

Back in 2011, we had a similar, but less serious, bout of snow and cold.

The episode has been widely referenced in the national discussion about Texas’ power outage and the failures of the Lone Star State’s power grid, which is independent from the rest of the country. A snowstorm the first week in February 2011 set the stage for the worst year in monarch butterfly history. The state went directly from an unusual freeze into what felt like summer, and then…into the hottest, driest summer since record keeping began in 1895.

The monarch migration’s two worst years in history followed. The overwintering butterflies occupied only 1.19 hectares/about three acres in 2012, and .67 / about 1.6 acres, the year after.

Hopefully 2021 will be different.

TOP PHOTO: Frozen pollinator garden on the San Antonio River. Photo by Monika Maeckle

Related posts:

- Wildlife death toll mounts in wake of historic Texas freeze

- Got frozen plants? Patience required in managing aftermath of historic Texas freeze

- 2020 monarch butterfly population drops 53%

- Entry to Mexico’s top monarch butterfly roosting site should cost more than $2.77

- Tropical milkweed impact on monarch butterflies “vastly overblown,” says longtime butterfly researcher

- Tropical milkweed OK for monarchs? “Just cut the dang stuff down”

- Tropical Milkweed: to Plant it or Not, it’s Not a Simple Question

- Q&A: Dr. Lincoln Brower on Milkweed, ESA, and Monarchs

Like what you’re reading? Follow butterfly and native plant news at the Texas Butterfly Ranch. Sign up for email delivery, like us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter, @monikam.

So sad to see this. Hope the butterflies find something for their long journey…

Houston – Everything in my garden was coming to life nicely and was on track to have the most milkweed ever, but after the freeze every flowering plant I have is dead to the roots if not completely dead. This cant be good for the monarchs the only good thing is I have about 100 milkweed seeds germinated and starting to grow but I doubt they will be big enough for the migration.

Article said: “A snowstorm the first week in February 2011 set the stage for the worst year in monarch butterfly history.”

The fall migration of 2011 was actually pretty strong in Texas:. 10,000+ observed in Fort Stockton & Sonora: https://journeynorth.org/sightings/querylist.html?map=monarch-roost-fall&year=2011&season=fall

I’m in Marble Falls, Texas. My new milkweed shoots froze. No nectar flowers available here yet.

Why would you add Tropical Milkweed back into an area where they just froze? You have an example further north in San Marcos where Antelope Horn, a native milkweed, survived so the path forward seems pretty clear. I do not understand the apparent addiction to the non-native Tropical Milkweed.

This is at least worth a comparative study of which species survived and which did not, then a deliberative action to acquire more of the surviving species.

I bought two milkweeds about a week ago, after my seedlings and a couple of ‘semi-perennials’ got toasted by the freeze. I spotted my first two females laying eggs on them today. I counted eggs, and got to about twenty. I may have to buy more plants if the cats outpace the milkweeds. I know a community garden that has a section of milkweed, and the mayor said I could ‘raid’ it, but who knows what kind of shape those plants are in.

No monarchs yet here in Austin so when do y’all think 🤔

Soon.

A lot of eggs laid on my store-bought milkweeds starting about two weeks ago have resulted in dozens of cats over the last week or so. As they get close to going to chrysalis and eventually to eclose, I was thinking about tagging some before they continued the journey North. But everything I’ve found and read seems to indicate that tagging only happens in the Fall return. Why is that? Because they become concentrated in Mexico, and recovery of the tags is better?