Our first Milkweed Guide posted back in the fall of 2010 and has continued to be one of our most-read blogposts. With spring here and butterfly gardeners chomping at the bit to create host and nectar habitat for Monarchs and other butterflies, it’s a good time to talk milkweed choices and availability.

Much has changed since that 2010 post. A three-year, drought-induced emphasis on native, drought-hearty plants has created a greater demand for native milkweeds. That said, supply continues to be lacking.

Monarch Watch recently launched its Milkweed Market on its homepage, a virtual marketplace of native milkweed seed. When you click on the vendors, though, most species are not available.

Monarch Watch, The Xerces Society, a pollinator advocacy organization, and the Native Plant Society have all engaged in milkweed restoration initiatives. This is good news, but it will take time to develop the market commercially.

Those of us who have attempted cultivation of native milkweeds from seed in our home gardens have often met frustration and failure. The very traits that make native plants so hardy also often make them extremely particular about their soil, drainage, moisture and available light. As George Cates, chief seed wrangler at Native American Seed Co. in Junction, Texas told me: “These milkweeds have a mind of their own.”

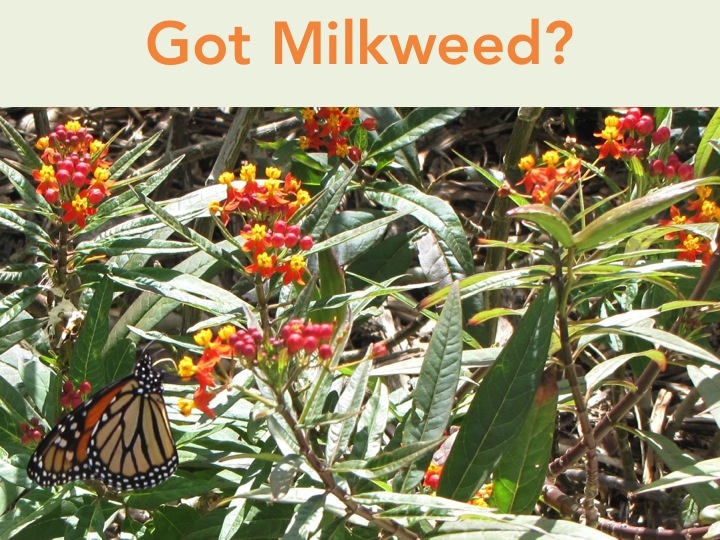

Monarch caterpillars will ONLY eat Asclepias species, or milkweed. Photo by Monika Maeckle

Plugs for native milkweeds are practically impossible to find in nurseries and because of their extremely long tap roots, transplanting them successfully often fails. Texas longterm drought has sparked a broader interest in native plants, so the availability of milkweeds and other “from here” pollinator plants will continue to grow.

For now, though, planting from seed is the most viable option. If you can collect your own seed in the wild, go for it. Native milkweed seed is expensive–as it should be. When you realize what it takes to produce the seed, you won’t begrudge its price tag. Read that saga here.

Since the time to take cuttings and collect seed will soon be upon us, we offer guidance below, based on personal experience. Other appropriate milkweeds are suggested in this article by the Native Plant Society. Keep an eye out for your local botanical garden or native seed society’s pop-up plant sales to score some proven homegrown natives.

Texas Butterfly Ranch Suggested Milkweed Species for our Area

Antelope Horn, Asclepias asperula

Antelope Horn, Asclepias asperula

The most common native milkweed in these parts has fuzzy leaves and an odd greenish-white bloom and can stand two-feet tall. During dry spring seasons, the hearty perennial is sometimes the ONLY plant blooming. Last year in Central Texas when we had an exceptionally wet winter, the Antelope Horns were not as pervasive as you would think. Too much moisture and too much competition from less hardy plants kept these guys laying low.

Antelope horns is especially appropriate for wildscapes, ranches, and large plantings. It can best be propagated by seed, which is available commercially from native seed suppliers.

Be mindful that stratification is recommended for successful germination. According to the Ladybird Johnson Wildflower Center, Antelope horns can also be propagated from root cuttings taken in the spring. If you have it growing in nearby fields, ranches or wildscapes, you might give this a try. If you choose to plant seeds you’ve gathered yourself, collect those in June.

Typically 30 – 45 days of stratification will be required before installing in moist soil. See our post on how to get Antelope Horns milkweed to germinate, courtesy of Native American Seed Company in Junction, Texas.

Asclepias asperula, Antelope Horns Milkweed on Texas Hill Country roadside in April 201, photo by Monika Maeckle

Green Milkweed, Asclepias viridis

This common native milkweed in our area is sometimes called Green Antelope Horn Milkweed or Green Mlikweed and is the most common milkweed in the state of Texas. The Edwards Plateau is the western reach of its range, which starts in East Texas.

I have a single one of these plants growing under a porch at the ranch. The solitary bloomer never receives supplementary water and barely enjoys rain, given its location tucked under a breezeway.

Yet every year it pushes out a batch of blooms and seedpods, peeking from under the deck, reaching for the sun. Those of us who raise Monarch caterpillars like the fact that Green milkweed has larger leaves than other available milkweed, which makes feeding voracious caterpillars a bit easier.

Green milkweed can range from one-three feet in height and is best propagated by seed which is commercially available. Like Antelope Horns, it sports showy whiteish-green globes of flowers that attract Monarchs as a host, and huge bees and other butterflies for its nectar.

Asclepia Viridis, Green Milkweed or Green Antelopehorn Milkweed Photo courtesy Ladybird Johnson Wildflower Center

Swamp Milkweed, Asclepias incarnata

Another excellent native milkweed for our area is Swamp Milkweed, a lovely pink bloomer that sports lush pink flowers in August and blooms through September.

Swamp milkweed grows along rivers and streams and is an excellent choice for riverbanks in the Hill Country or perhaps in an area where you have air conditioning condensate draining. Spiders LOVE this plant. I have witnessed “death in the afternoon” more often than I care to remember: Monarch butterflies snagged by orb weaver spiders as they perch on Swamp Milkweed leaves, in search of an easy feast.

For years we’ve had this milkweed growing along the banks and on the Chigger Islands of our Llano River ranch, but recent, prolonged drought has taken a severe toll, lowering our water table so much that much Swamp milkweed has died.

Monarch on Swamp Milkweed on the Llano River, photo by Monika Maeckle

Butterfly Weed, Asclepias tuberosa

This bushy orange bloomer is often confused for Tropical Milkweed (see below) and is frequently mislabeled at nurseries. One of the best ways to tell if a milkweed in question is tuberosa is to break off a leaf and see if milky latex pours out. If it doesn’t, then it’s Butterfly Weed.

Detractors of Butterfly Weed point out that it doesn’t contain the toxic cardenolides that protect Monarchs from predators, thus should be avoided. The toxins, contained in the latex of most milkweed species, give the Monarch its bright warning colors and bad taste that deters predators.

The 18-inch-tall perennial serves as a fantastic nectar plant. Its abundant orange blooms attract all kinds of butterflies. If you’re trying to stick with natives, choose this one to grace your butterfly garden.

Butterfly weed can sometimes be found locally at nurseries. The plant is propagated easily from seeds and cuttings and blooms through the Fall, when nectar sources are wanting.

Asclepias tuberosa, or Butterfly Weed, will be growing soon at the White House Pollinator Garden. Photo courtesy Ladybird Johnson Wildflower Center

Tropical Milkweed, Asclepias curassavica

Tropical milkweed is not native, but it is widely available at garden centers in one-gallon pots and it also germinates easily from seed and cuttings. As much as I support native plants, this is my favorite Monarch host plant. It’s easy to grow, not a water hog, propagates easily from seeds and cuttings, blooms prolifically and draws Monarchs like a magnet. Commercial butterfly breeders and even organizations like Monarch Watch rely on Tropical milkweed to raise butterflies in captivity.

The plant can be controversial for native plant purists and some scientists. Theories abound on the appropriateness–or not–of Tropical milkweed in Central and South Texas.

The plant originated in Central America and has gradually moved north. Dr. Chip Taylor, founder of Monarch Watch, points out that Tropical milkweed is the plant on which Monarch butterflies evolved.

In my completely unscientific kitchen experiments, I’ve noticed that Monarch caterpillars PREFER Tropical milkweed. When offered a choice of Tropical milkweed, Swamp Milkweed or Antelope horns, Monarch caterpillars inevitably choose Tropical milkweed.

Studies show that the toxins in Tropical Milkweed inoculate Monarch moms and their young.

While it can be challenging to find Tropical milkweed in the Fall when Monarchs are moving through Texas, it’s easy to cut back your spring plants to encourage new growth for migrating visitors. My butterfly breeder friend Connie Hodson, of Flutterby Gardens in Manatee, Florida, says you can cut any six-inch stalk of Tropical milkweed in a potting soil and vermiculite mix, and have new plants in no time. You can also order seeds or harvest them yourself from fellow gardeners.

NOTE: If you choose to plant Tropical milkweed, best practice suggests slashing it to the ground in late fall or early winter. It will push out new shoots as the weather warms. This will discourage overwintering of organisms possibly harmful to Monarchs.

Asclepias curassavica, Tropical milkweed, NOT native, but a great Monarch host and nectar plant for all butterflies. Photo by Monika Maeckle

Asclepias curassavica, Tropical milkweed, NOT native, but a great Monarch host and nectar plant for all butterflies. Photo by Moniak Maeckle

Pearl Milkweed vine, Matelea reticulata

While Milkweed vine is in the Asclepias family, there doesn’t seem to be any evidence that Monarchs and Queens use this vine as a host plant. It grows in the wild in the Texas Hill Country.

Anyone have experience with Milkweed vine as a host?

I include it today because it is an absolutely delightful plant with its heart-shaped leaves, perfect green symmetrical flowers, and a lovely, intriguing pearl-like dot in the middle. Someone needs to make earrings out of these flowers.

In the Fall, Milkweed vine produces huge seed pods, about three times the size of Tropical milkweed. The plant climbs and curls for six – 12 feet and is sometimes called Green milkweed vine, Net vein milkvine, and Netted milkvine.

- How to Get Native Milkweed Seeds to Germinate

- Tropical Milkweed: To Plant it or Not is No Simple Question

- Desperately seeking MIlkweed: Be sure to buy pesticide free plants

- Butterfly FAQ: Is it OK to Move a Chrysalis? Yes, and here’s how to do it

- How to Make Seedballs

- Converting your Lawn to a Butterfly Garden

Milkweed vine

Like what you’re reading? Follow butterfly and native plant news at the Texas Butterfly Ranch. Sign up for email delivery in the righthand navigation bar of this page, like us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter, @monikam. You can also read our stuff on the Rivard Report.

Monarch and queen caterpillars have been documented using Pearl Milkweed Vine in Kendall County.

That’s great news, Kip. I will check ours next time. Thanks for chiming in.

–Monika

Hi there, we are in Texas, Zip code area 78634 and THE most popular plant for Queens to ovodeposit on here in our land are all the Matelea Reticulata. It is almost invisible and you can hardly find the plants as a low growing vine but each and every time I check between April and October there are Queen caterpillars on there! Don’t have ANY on the native milkweeds we also have (viridis, syriaca, texana, asperula) but sure enough on the MR. cheers

I think the vine is so lovely~ where would one find it in SA?? also last spring and fall my tropical milkweed plants were devoured by hungry monarch caterpillars but they have not been touched this year , save for the aphids that have destroyed several blooms. Also I have not seen any actual butterflies in my yard yet have spotted a few here and there around town and in surrounding areas. I hope this is just bad luck and not a sign that they are dwindling in #’s as some articles and research has been indicating:/

I know, isn’t it charming. I have never seen it anywhere except in the wild. I suggest asking our friend Google–she knows everything.

–Monika

Ugh — those yellow aphids. I remember blasting them off with the hose a few times.

It has been my experience here in NC that the Monarchs prefer the tropical milkweed and their least favorite is the butterfly weed. I have the best luck with growing common milkweed and always have lots of caters.

For those who haven’t seen this, watch it. These teachers have done a wonderful job teaching about the Monarchs’ plight and the kids are delightful. This was posted by Brenda Dziedzic on Save the Monarchs’ Facebook page. http://m.youtube.com/#/watch?v=cisfqvCeCo0&desktop_uri=%2Fwatch%3Fv%3DcisfqvCeCo0

Anyone wanting Milkweed seeds please email me and I will send you some, I have red tropical, yellow, orange and showy milkweed seeds!

Renexxxxxx@aol.com

When do you plant the seeds and do you still have some? I would love to have some.

Nbryant@dishmail.net

Thank you!

Nan Bryant

I see this was from a year ago, but if you still have ample supply and it’s not too late to start/plant along the upper Tx. gulf coast, could you send some to me?

If your offer of milkweed seeds is still good, I’d love to have some.

I am wondering if you have any extra butterfly weed seeds available?

If you do I would be interested in getting some seeds.

Can you email a photo of the plant too?

Thanks!

Evelyn

Please I live in Abilene Texas. I would love some milkweed seed. I’ve seen only one monarch this year and it concerns me. Our growing season is about a month late this year.

I had previously bought Butterfly weed (tuberosa) from Home Depot and I went outside the other day and have 7 huge caterpillars! They sucked the leaves dry on the plant and then 5 left to walkabout and I found them on my monkey grass and put them back. I have now bought two more huge tuberosas and 1 through 2 have been transplanted onto the new plant. They are so happy and I found an egg on one of the leaves!!! Will 3-7 come back? (I am sooo excited as I did this in Environmental Science in high school in SA, and I have named them one through seven)

THey likely will not return. Either they went off to form their chrysalises, became a butterfly and flew off, or a predator got them on the way. Keep up the good work!

How do I correctly cut back my milkweed so that it continues to produce leaves/food for my now 10 baby caterpillars????

Just prune as you see fit. In the winter, cut it down to the ground. It will take time to regnerate and you may need to go buy some fresh milkweed at a local nursery. Be sure to verify that it has not been sprayed with any systemic pesticides. Good luck!

Is anyone familiar with is research? Some scientists suspect that misguided attempts to help the monarch in the United States may be accelerating the end of the migration. U.S. scientists have been encouraging midwesterners and Texans to plant milkweed, but many people have been planting the wrong variety: Asclepias curassavica, a species that usually grows in the tropics. Tropical milkweed does not die back in the winter, providing monarchs with a year-round food source that may eliminate their need to migrate, Oberhauser says.

Staying in one place for many generations makes the butterflies more susceptible to the deadly Ophryocystis elektroscirrha parasite. According to Lincoln Brower, a biologist at Sweet Briar College in Virginia, the “insidious disease” spreads when infected butterflies scatter spores on milkweed plants, which are then ingested by the next generation of caterpillars. If fewer butterflies migrate to Mexico, he says, the proportion of infected monarchs across North America may increase, imperiling the whole population. news.sciencemag.org/biology/2014/01/monarch-numbers-mexico-fall-record-low

The tropical milkweed is not a problem in North Central Texas, Dallas/Fort Worth. It does die down, and we can cut it down. It does reseed wherever it feels like. The Monarchs do seem to like it so much better. I use the analogy of choosing between ice cream and spinach. Other milkweeds here do have trouble flowering and returning. We let nature take its course. Biggest problem is new emerging butterflies in December and January.

If you didn’t have the tropical milkweed, butterflies would not be eclosing in the wrong time of year. Our Texas native milkweeds are dying back in the fall and female monarchs heading south to Mexico are in diapause ( egg laying on hold), as they need all of their energy for that long journey. If they see tropical milkweed, they can be induced out of diapause to lay eggs, which they absolutely should not be doing, because this expends their energy, (among other negative aspects) Monarchs only need milkweed in Texas in the spring as they head north. These first eggs are the first generation of monarchs. Texan’s should only have nectar plants available in the fall the fuel the migration. If you must use tropical, please cut them down by the end of summer. Their flowers can support other insects. I had tropical milkweed when I first became interested in attracting monarchs. I bought the plant in the spring or summer of 2021. I didn’t get any monarchs ( dallas area) until august. The few that survived predators and made it to butterflies in august seemed to be ok. But the later ones-(sept-October) seemed deformed and unable to fly. It was extremely sad and I had to eventually end their misery.

[…] you want to know more about the milkweed choices for Central Texas, check out this great blog, Texas Butterfly Ranch, by Monika Maeckle. She profiles beautifully the various milkweed species for this area. Being […]

Your link to the Native American Seed Co. is wrong. It links to seedsource.org, whose owner I cannot discern as the page is in Japanese. The correct link is seedsource.com.

Local nursery advising folks to: KILL YOUR MILKWEED

Can you correct them? I don’t think this is good info.

From: Hill Country Water Gardens & Nursery

Date: Thursday, October 1, 2015 at 5:03 PM

Subject: You can have an orchard! + New Seminars for Fall 2015

It’s butterfly migration season! Feed those Butterflies! Butterflies will be in search of fuel as the make their journey south for the winter. We have their favorite fuel sources in stock now.

Please note:

KILL YOUR MILKWEED NOW! Well…chop it down. We need the Monarchs to get back to Mexico and they’ll think they’ve made it home when they find your milkweed. Let them refuel and move on, the eggs and caterpillars will not make it through our winter here in Central Texas! Thank you for your understanding!

1407 North Bell Blvd.

Cedar Park, TX 78613

Just 1/4 mile north of FM 1431 on Hwy 183

512-260-5050

http://www.hillcountrywatergardens.com

Milkweed seeds can be ordered dirt cheap from Linda Auld in New Orleans. Her email is nolabuglady@gmail.com

I’m in Florida on the west coast central. Has anyone had any luck with Honeyvine Milkweed. I’m told it is also a host pant for the Monarch’s.

I’m desperately searching for a Milkweed plant for my 8 caterpillars. I live in Nederland in SE TX. Does anyone have any near me?

I’m not near – zip 78681 – but have just a few currassavica cuttings that have some leaves left, I would need to check if they survived the week in the Greenhouse. Cheers, Sandy

Linda, I found plants at Ritter in Beaumont and I was also told that Al Cook has them. Good luck!

[…] tallest. Only a few more days before all the fire-colored blossoms have opened. Happy sunbursts of milkweed stand ready for monarch butterflies, glowing against brackets of bright red possumhaw holly and […]

Nobody will believe me, but monarch caterpillars eat one of my other plants. I bought a hanging succulent called “string of hearts” four years ago. I hang it outside every summer. I noticed two years ago that something was eating it, so I brought it inside. Well four days later I noticed 3 monarch caterpillars munching on it. And the same thing happened last year. I have butterfly gardens and plant milkweed. Now I hang this plant in my gardens with pin cushions plants. I will again investigate.

You should post a video. I suspect you are misidentifying another caterpillar as a monarch.

I see someone posted here just last month, so hopefully people are still finding this great page!

I’m in Austin, and a few years ago, my pearl milkweed vine first appeared out of nowhere, growing in the shade under my mountain laurels and climbing up the trees. I quickly became enamored of the thumbnail-sized flowers as soon as I started photographing them with macro.

Last year they started spreading out, even migrating to the other side of the driveway. It was then that I discovered first dozens of larvae on one leaf, and later a few fuzzy black/orange/white — tiger colors — caterpillars. Through a Google search I discovered that they were milkweed tussock moth caterpillars, the only host I’ve ever seen on the plants. (The cats are infinitely more appealing than the moths.) In fact, I didn’t even know what my vines with the “little greenies” (blooms) were until the search for the caterpillars led me to the info. Love my little greenies! I had two tropical milkweed plants a while back, and one day found four queen caterpillars on them. They were gone the next day. Ultimately, the tropicals didn’t survive and I’ll have to plant some more.

I’ve seen Queen caterpillars using the Pearl Milkweed Vine one year. Since I have Tropical Milkweed and Texas Milkweed, the butterfly mamas normally prefer those two over the Pearl Milkweed Vine.

Hi! I’m new on this page and live in New Braunfels, TX, 78132. I’m growing a tropical milkweed next to my pond and it is now around 4 ft. tall and full of blooms…..when can I expect to see monarch cats on it and when do I cut it back? Thanks, Nadine

I am new and want to stay updated on the milkweed movements in TX.

Katrina, check out this website: https://journeynorth.org/monarchs

They track the Monarchs’ migration each spring and fall. I’m in Houston and they are usually here in October and November in the fall.

I have had the hardest time getting milkweeds to establish in my San Antonio and Laredo gardens. I have tried antelope horn, green, swamp, common, tuberosa, Texas, Zygote (or whatever you call that one), and showy. The only one I’ve had any luck with has been tuberosa. I keep trying, and presently have some antelope horn and showy seedlings that I will once again transplant.

You had recommended going to Barton Springs Nursery for help and selection. The website says they were acquired by Bearing Growers at 973 Farm

Are these also knowledgeable people or are there better sources in Austin?

I currently have 15 Queen caterpillars from eggs on my pearl milkweed.

Northern Hays County, Texas

I have 3 caterpillars on my milkweed in Rockwall, TX. I appreciate the info here. One is much smaller and I may bring inside to care for!

For anyone in the North Dallas area, if you’re still seeking milkweed, I can recommend Painted Flower Farm in Denton. They specialize in Texas native plants, and I’ve been able to get several from them (A&M Superstars, in particular) when I could not find them anywhere else. In past years, we have bought both green and antelope horn milkweed from them, and it is pesticide-free. They don’t sell seeds, just plants, but we’ve loved everything we’ve gotten from them (including Big Momma Turk’s Cap, tickseed and Texas columbines) and they have all been strong and healthy. http://www.paintedflowerfarm.com/

For those with a wider interest in butterflies, the native Passiflora Incarnata (Maypop/passionflower/passionfruit) has been a fabulous host for gulf fritillaries in my yard, has lovely flowers – and comes back from the roots in the spring, likely in several additional locations…

Agreed!

At my old house (I moved in August 2022 and can’t believe my previous post is nearly five years old!) I had several different types of passion vine over the years. Maypop, Lavender Lady, Blue Crown, and Incense. The Incense did GREAT. Frilly purple flowers and it multiplied all over the place, Had wires strung from my fence to the house and one summer had a very thick canopy. I loved it to pieces. The last year or so I had a number of Gulf Fritillary chrysali (is that the plural?) and got to see a few right after emergence. I also finally got seven or eight monarch cats on my Mexican milkweed one season, but they decimated the plants pretty quickly and disappeared. I live in a tiny home community now. They told us last winter we could finally put a small flower bed on our lots — like REALLY small. I was still waiting for sod! Right before Thanksgiving I finally got the sod. The property manager had left so everyone was breaking the rules and I had my ex put in metal edging for a bed around 4 feet deep and 24 feet long, along the side of my house. We did it after they laid the soil and before they laid the grass a few days later. Too late to plant so just topped it off with mulch. Around that time I saw some passion vine at Great Outdoors (my favorite urban nursery here) called Inspiration. I asked one of the workers if it was the same as Incense because the flower in the picture looked pretty much the same. I was told it was a hybrid. At any rate, I plan to fill the bed in the spring, and hopefully find some good passion vine at that time to climb up my porch railing (porch is five steps above the ground.) There is a farm in the center of the community but I’ve seen VERY few bees or butterflies around here. Maybe this year more people will plant some good pollinators. I’m certainly going to do my part!

Oh yeah — and the Incense always came back after a freeze even better, no matter how harsh the winter was. Sprout up all over the yard. I may just go and ask the buyers of my old house if I can dig some up! There will be so much they would never miss it.

I wrote a long reply about passion vine, and it was awaiting moderation. I don’t see it now so hope it didn’t disappear!