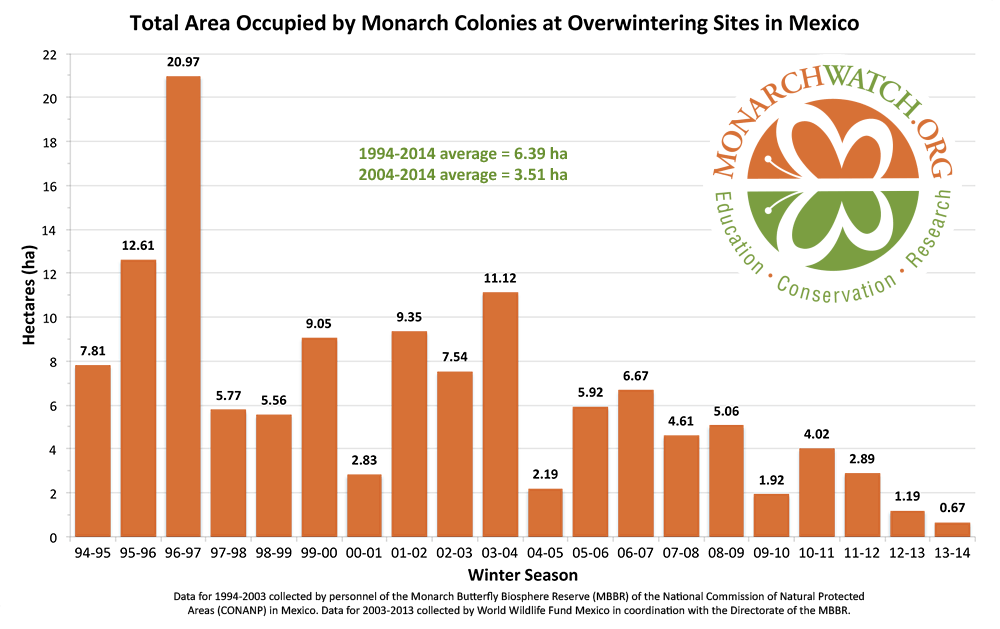

More alarming news from the Monarch butterfly roosting sites in Michoacán last week: the 2013 season will surpass 2012 as the all time worst year for Monarch butterflies since records have been kept.

Ever since 1994, scientists have measured the hectares occupied by the migrating insects in the high altitude forests west of Mexico City to get an idea of their numbers. That information typically works as a key indicator on the state of the union of Monarch butterflies and other pollinators, which fertilize 70% of the world’s flowering plants and two-thirds of the world’s food crops.

For the 2013 season, the entire migrating Monarch butterfly population occupies only .67 hectares. That’s 1.65 acres, 72,000 square feet–or about 35 million butterflies, down from highs of 450 million in years’ past. Think about it: the entire population of migratory Monarch butterflies could easily fit into the average Walmart store, with 30,000 square feet to spare.

Headlines trumpeted the end of the migration.

“Monarch butterflies drop, migration may disappear,” the Washington Post reported. On January 29, NBC Nightly News anchor Bryan Williams told viewers–incorrectly–that the head of the World Wildlife Fund in Mexico said the Monarch butterfly is in serious risk of disappearing. In fact, it’s the migration that’s endangered, NOT the butterflies. Important point.

The New York Times put the dismal news in proper perspective: “The migrating population has become so small—perhaps 35 million, experts guess—that the prospects of its rebounding to levels seen even five years ago are diminishing. At worst, scientists said, a migration widely called one of the world’s great natural spectacles is in danger of effectively vanishing.”

The news cast a pall over Monarch watchers and other nature lovers.

“My whole day got grayer,” said David Braun, an attorney, naturalist, and founder of Braun & Gresham, a law firm that specializes in environmental and land management issues in Dripping Springs, Texas.

Like me, Braun lives in the Texas Funnel, the primary flyway through which all migrating Monarchs must pass in the fall on their way to Mexico. He has accompanied me over the years on Monarch tagging outings along the Llano River and led ecotravelers to the roosting spots in Michoacán for Victor Emanual Tours back in the 1980s. He was the first person to spark my imagination about how truly awesome it would be to witness the spectacle of hundreds of millions of butterflies unleashed in a mountain forest.

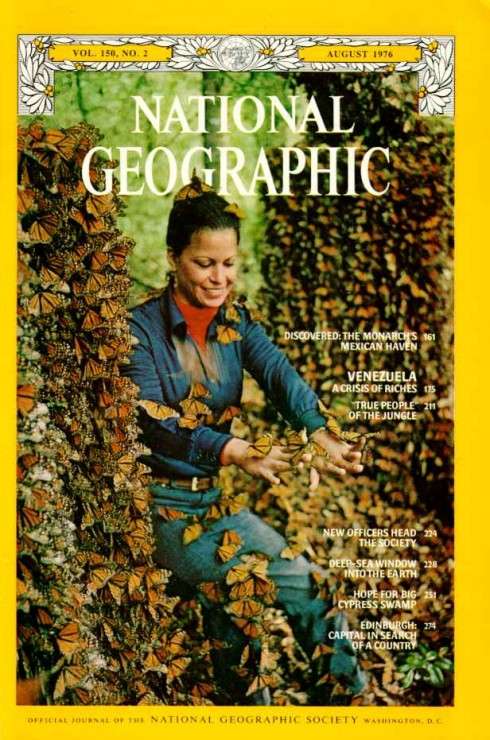

Look at all those Monarchs! Catalina Trail, then known as Cathy Aguado, discovered the roosting sites and appeared on the cover of National Geographic in 1976. Photo by Monika Maeckle

“I remember clearly my excitement when the National Geographic story came out in 1976 announcing the discovery of the wintering grounds,” Braun wrote via email. “I also remember my first trip there, the magic of walking through the hushed, cathedral-like fir forest and hearing the sound of millions of Monarch wings flapping. Today, I have to wonder if that entire awe-inspiring, glorious natural wonder will disappear in my lifetime. It makes my short life seem even more insignificant if the great cycles of nature aren’t timeless.”

Thousands of others echoed those sentiments via social media, in comments on dozens of news articles, and in emails, on listservs and conversations near and far. For a sampling of angst, see the Monarch Watch Facebook page comments.

“What’s happening to Monarchs is probably happening to lots of species,” Dr. Karen Oberhauser, a professor at the University of Minnesota and founder of the Monarch Larvae Monitoring Project, told the Washington Post. “This is a species, unlike most other insects, that we can count and look at what we’ve done to it. So this really should serve as a wake-up call.”

Dr. Chip Taylor, founder of Monarch Watch, which oversees the citizen scientist tagging program in which I participate, reinforced the connection to other pollinators on the public radio program Here and Now.

In a comprehensive interview with WBUR, Taylor underscored the idea that this extreme and rapid decline is not just about Monarchs. “Monarchs are simply a flagship species for everything else that’s happening out there,” he said.

Taylor noted that Monarchs live in marginal habitats that support most of our pollinators– in roadside wildflower patches, between rows of cultivated crops and in native wildflower prairies. These spaces are too often decimated by habitat loss. Read his compelling explanation of the decline on the Monarch Watch Population Status Report.

“Those marginal habitats support a lot of small mammals and ground-nesting birds, and if we lose the monarchs, it means we’re going to lose all those things,” Dr. Taylor said. “People perhaps do not grasp…that it’s the pollinators that keep everything knitted together out there….there’s a fabric of life out there that maintains these ecosystems, and it’s the pollinators that are critical.”

More posts like this:

- On the Llano River:

- How to tag Monarch Butterflies

- Founder of the Monarch Roosting Spots Lives a Quiet Life in Austin, Texas

- Monarch Butterflies: the Panda Bears of Climate Change?

- Tracking the Monarch Migration from Your Desk

- A Year in the Life of a Mostly Native Urban Butterfly Garden

- As the Earth Heats Up, What Does it Mean for Monarch and other Migrating Butterflies?

- Monarch migration stories on the Texas Butterfly Ranch

Like what you’re reading? Don’t miss a single post from the Texas Butterfly Ranch. Sign up for email delivery, like us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter, @monikam.

I saw this piece in the NYT. Grim news, indeed. Aside from the specific beauty of the monarchs, the most depressing aspect of it was the linkage between the monarchs and the decline of other species which occupy marginal habitats. Ken

What about the western Monarchs that go to the trees in California? How are their numbers doing?

My understanding is that had a rebound this year. However, that sounds like a good topic for a future blog post! –MM

Where can I purchase enough milk weed seeds and some plants to do my 30+ acres in San Antonio Tx?

peterttt@satx.rr.com.

Peter, you may find it isn’t easy to grow a large acreage of native Texas milkweed: https://texasbutterflyranch.com/2013/03/13/persnickety-texas-milkweeds-may-not-lend-themselves-to-mass-seed-production/

I would try Native American Seed in Junction, Texas. You can also try Douglas King Seed in San Antonio or the Monarch Watch Milkweed exchange. Good luck!

Thanks.