Graduate student Dara Satterfield caused quite a flutter recently when she was featured in the New York Times as the co-author of a study looking at how Tropical milkweed, Asclepias curassavica, may be effecting the health of Monarch butterflies and their Pan-American migration. Her dissertation focuses on the relationship between migration and infectious disease in wildlife, with Monarch butterflies as her species focus.

Dara Satterfield, PhD candidate at the Odum School of Ecology at the University of Georgia.. Photo by Monika Maeckle

In the article headlined For the Monarch Butterfly, a Long Road Back, and promoted heavily online as “Monarch Butterflies: Loved to Death?” science journalist Liza Gross explored the pros and cons of planting Tropical milkweed. To read our original story on this topic, check out Tropical Milkweed: To plant it or not, it’s not a simple question.

Satterfield, a PhD candidate at the Odum School of Ecology at the University of Georgia, and other scientists speculate that Tropical milkweed, the most widely available but technically nonnative milkweed and favorite host plant of the Monarch butterfly, may be damaging the Monarchs’ abilities to stay healthy, on track and make their way to Mexico.

“She and her graduate adviser, Sonia Altizer, a disease ecologist at Georgia, fear that well-meaning efforts by butterfly lovers may be contributing to the monarch’s plight,” said the article.

I caught up with Satterfield recently to ask questions that have arisen since the article posted on November 17. She expressed concern that the NY Times article might have confused some readers–and no doubt the issue is confusing and complex. Hopefully the Q & A below will clarify matters a bit.

Q: I’ve talked to several scientists that insist that Tropical milkweed is the plant on which Monarchs evolved. Do you agree with that?

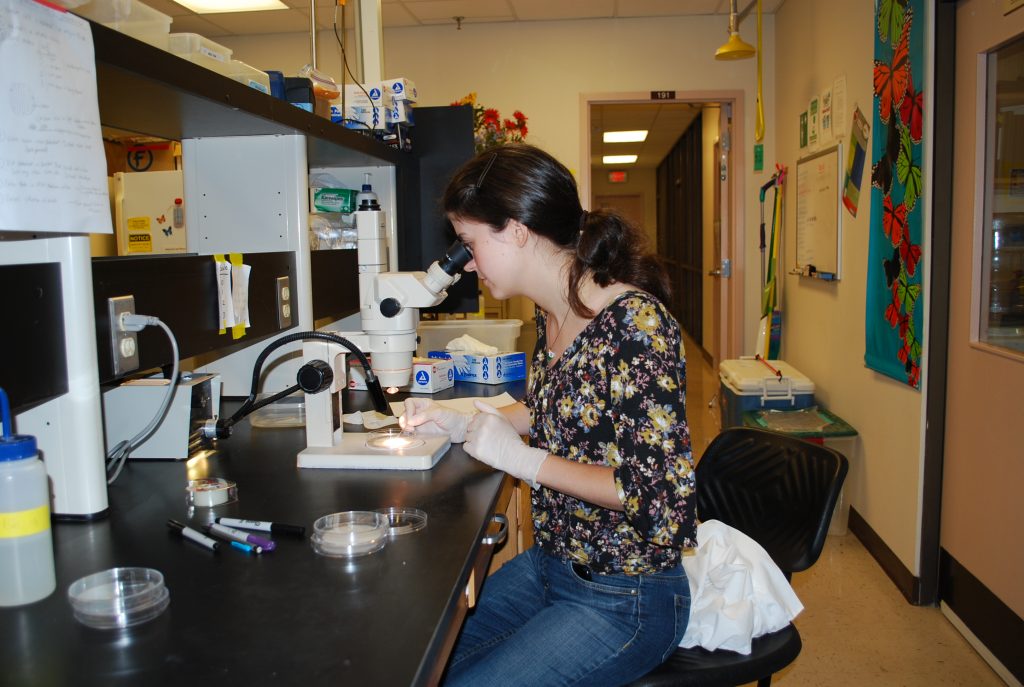

PhD candidate Dara Satterfield doing field work on Tropical milkweed and the Monarch butterfly migration. Photo courtesy Dara Satterfield

A: Good question. From what I understand, the historically held view was that Monarchs evolved from a tropical ancestor from Central or South America, and so some scientists have said they must have used Tropical milkweed and other exotic milkweed species early in their speciation.

New evidence suggests a different story. The recent Nature paper examining Monarch genetics revealed that, actually, Monarchs appear to have originated in North America (and would have evolved on native North American milkweed species) and the other Monarch populations in Central America, South America, the Pacific, etc. (some of which would use Tropical milkweed) came from the North American population.

Q. You have said that Monarchs are much more likely to be sick in places where Tropical milkweed grows year-round–but is it really Tropical milkweed (Asclepias curassavica) that is the problem? If Common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca) or Swamp milkweed (Asclepias Incarnata) also survived a winter and were available, would the same tendency apply?

A. You are correct, I think. The same disease problem would probably occur with any milkweed species that grew year-round in warm areas and was attractive to Monarchs. It just happens that Tropical milkweed is the species that does stick around. We don’t think Tropical milkweed itself is bad; it’s the year-round growth that is harmful because it promotes disease. Also, I’d just like to add that we would not even understand this problem without the help of dedicated volunteers and citizen scientists who share observations and collect data. Much of what we know about Monarch ecology can be attributed to the help of citizen scientists.

NOTE from Texas Butterfly Ranch: Thus, best practice suggests slashing all milkweeds to the ground in late fall if they do not die back from freeze. This prevents OE spores from building up and spreading disease.

Satterfield in the lab, checking for OE spores. Larvae can acquire OE infections by eating parasite spores on milkweed leaves, left there by an infected butterfly (often, the larva’s mom). Courtesy photo

3. What is the purpose of a migration? If everything an insect needs to complete the life cycle is available locally, what interest is there for the insect to migrate?

For most migratory species, the purpose of migration is to track seasonal changes in climate or resources needed for survival and reproduction. Without human interference, migration as a strategy can often support large numbers of animals, because migratory animals may take advantage of the best resources–in different parts of the world at different times of the year (e.g., red knots that travel from the North Pole to the South Pole to experience summer in both hemispheres).

Monarch caterpillar on Tropical milkweed. The larvae can pick up OE spores through contact with other creatures or from plants on which the spores rest. Courtesy photo.

But some migratory populations including birds, bats, fish, and hoofed animals are altering their migrations–shortening or halting their journeys–in response to human activities like barriers in their migratory pathways (e.g., dams), changes in climate, and human-provided foods. Examples of this abound (No Way Home, by David Wilcove). Of course some of these newly non-migratory animal populations will be just fine and learn to adapt to new circumstances, but others will not.

Consequences will include changes in infectious diseases, loss of ecosystem services associated with migration (e.g., nutrient transfer between ecosystems by salmon, control of insect populations by birds), and in some cases, species extinction.

For Monarchs specifically, their migration allows them to have a large population capacity. If Monarchs solely engaged in winter-breeding, rather than overwintering in Mexico, this strategy could likely only support a much smaller population. So we try to conserve the abundance of migration.

Of course, individual animals operate on an individual basis and do not make choices based on what is best for the population at large, so individual animals will often take advantage of resources that are available to them–for example, why go to Mexico when I have everything I need here?

The problem with that, in this case of year-round milkweed and year-round Monarch breeding, is extremely high levels of protozoan disease as well as risks of winter starvation (running out of Tropical milkweed) and freeze events that kill caterpillars. The concern is also that migratory Monarchs (or their offspring) might be exposed to parasite-contaminated milkweed in the spring.

All of that said, Dr. Chip Taylor is correct that the link between year-round milkweed and disease is by no means the largest threat to Monarchs.

However, given what we now know about this problem, we have the opportunity to reduce disease in Monarchs by keeping milkweed seasonal rather than available all year.

Related posts:

- Tropical Milkweed: to Plant it or Not, it’s Not a Simple Question

- Endangered Species Act: Wrong Tool for the Job of Monarch Butterfly Conservation

- Milkweed Shortage Sparks “Alternative Fuels” for Monarch Butterfly Host Plant

- It Takes a Village to Feed Hungry Monarch Caterpillars

- Desperately Seeking Milkweed: Milkweed Shortage Creates Butterfly Emergency

- Pollinator Power on the San Antonio River Walk

- 2014 Monarch Butterfly Migration: Worst Year in History or Hopeful Rebound?

- How to Raise Monarch Butterflies at Home, Part One

- First Lady Michelle Obama Plants First Ever Pollinator Garden at the White House

Like what you’re reading? Follow butterfly and native plant news at the Texas Butterfly Ranch. Sign up for email delivery, like us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter, @monikam.

All the temperature zone latitude populations of monarch butterflies outside North America are supported solely by introduced non-native evergreen tropical milkweeds. Has the tropical milkweed caused those populations to become non-migratory? No. Or caused them to have devastatingly high levels of the OE parasite? No. So migratory monarch conservationists in southwestern Australia and New Zealand understandably favor planting MORE tropical milkweed, not less. They understand the more tropical milkweed = more migratory monarchs, not less.

Citizen scientists in San Antonio have participated in O. e. research for the past 3 years. We monitor monarchs on tropical milkweed planted in garden landscapes along the San Antonio River by San Antonio River Authority. We begin our monitoring this year on Dec. 6 at 10:30am at the milkweed patch at Schiller and Quincy. Join us!

Perfect is the enemy of good. As I understand the conclusions about the OE affect claimed to be aided by tropical milkweed have not been verified independantly by other researchers. As such I would warn readers to be careful of conclusions no matter how well intended concerning the planting of tropical milkweed. Cutting these plants back periodically in the fall is however good for the plant and will result in more leaf growth i.e.. more food for the cats.

Dr Grant, Is OE carried in the stem or the leaf of tropical milkweed? Once a stem is stripped of leaves by the caterpiller, I have cut the stem back by half and allowed to leaf out. Are you suggesting the stem be cut back to soil level?

Thank you.

Susan

Cut tropical milkweed off 2″ above the ground. As I understand the research OE appear on not in milkweed. This would allow the plant to put out new growth which is what we want.

Thank you. I will be more aggressive in pruning.

Thousands of tropical milkweed plants grow in the wild in northeastern and central Mexico and migratory monarchs lay eggs on them in the fall/winter/spring. In the spring those tropical milkweeds in Mexico generate northward bound migrant monarchs that help repopulate the eastern USA. If it became a fad in Mexico to cut back the tropical milkweed in winter, it would devastate the winter and spring monarch breeding populations. So I am against cutting back tropical milkweed because it does far more harm than good.

Paul I do not disagree with your statements given the circumstances you describe, and this may also apply to the Rio Grande Valley of Texas. The point I was trying to make was that cutting back tropical milkweed in the fall was preferable to cutting them off so as to kill them. In Virginia where we find ourselves in the spring the Tropical milkweed have reseeded themselves in the spring after the frost has killed all of the older plants, however in the Rio Grande Valley no frost occurs or only rarely and plants grow tall and leggy and need to be trimmed back to encourage more leaf growth. As you point out very well it is wrong headed to make statements that appear to be universal.

If the presence of tropical milkweed promotes off season breeding, then why isn’t there an off season breeding problem in Mexico where the milkweed is native?

Monarchs are cold blooded unlike other butterflies. This is probably one contributing factor to why they migrate. In climates such as Florida and California they have established colonies year round. I suspect that the weather contributes more to the lack of migration in these areas rather than the tropical milkweeds or for that matter any other type of milkweed.

I don’t believe there is an off season breeding “problem” to begin with. Here’s a 7 minute video showing what happens when a large amount of evergreen tropical milkweed is planted next to a monarch overwintering site along the California coast: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YCw7Ty9TBiU As you can see, 99.9% of the overwintering butterflies ignore the tropical milkweed. So the presence of the tropical milkweed is not altering the physiology of the overwintering butterflies causing them to breed off season. However, it’s normal for a tiny percentage of the fall migratory and overwintering population to develop eggs during the fall and winter and of course those butterflies go searching for milkweed. The presence of tropical milkweed gives those few butterflies a chance to pass on migratory offspring instead of dying without breeding.

Several commenters have shrewdly observed an excellent point: Tropical milkweed grows (often year-round) in Mexico and throughout central America. Interestingly, we don’t see the same OE disease problems there. While we know less about disease patterns in these areas, some past data suggests OE levels are lower in central America milkweed patches than in year-round tropical milkweed gardens in the coastal U.S. We think the difference might occur because tropical milkweed patches in central America show MUCH lower densities of monarch larvae/eggs. This means that even when OE spores are deposited on a leaf, the chance of a monarch larva actually eating that particular leaf is small. The wet-dry seasonality might also affect disease outcomes. Thank you for this interesting discussion!

[…] https://texasbutterflyranch.com/2014/12/03/q-a-grad-student-dara-satterfield-on-tropical-milkweed-and… […]

I kind of think we are not in a place to come to any conclusions as the investigations are so new, so few and there are so many variables not accounted for. Has the increased use of pesticides and herbicides weakened immune systems? Are we actually seeing a change in migration or is it normal for some percentage of the population to linger? Has anyone teased out the effects of climate change? Temperature plays an important role in triggering migrations. I also wonder about where and when the butterflies are getting sick or if this parasite is a feature that normally controls butterfly populations but the effects seem magnified because of the other pressures on the population.

[…] referenced the tropical milkweed research by Dara Satterfield, PhD candidate at University of Georgia. Satterfield works closely with Monarch scientist Dr. […]