The 2018 monarch butterfly migration is off to a great start.

Members of the DPLEX, an email listserv and online community that includes hundreds of monarch butterfly aficionados throughout Canada and the U.S., have begun the annual frenetic email exchange launched by monarch season. Their reports suggest a banner year.

Monarchs gather on upland boneset in Wauwatosa, Wisconsin. Photo by Carol Fibich, Friends of the Monarch Trail

Butterfly watchers in Ontario, Michigan, and northern destinations report an ample supply of the iconic black-and-orange insects, which should arrive en masse in Texas in about six weeks.

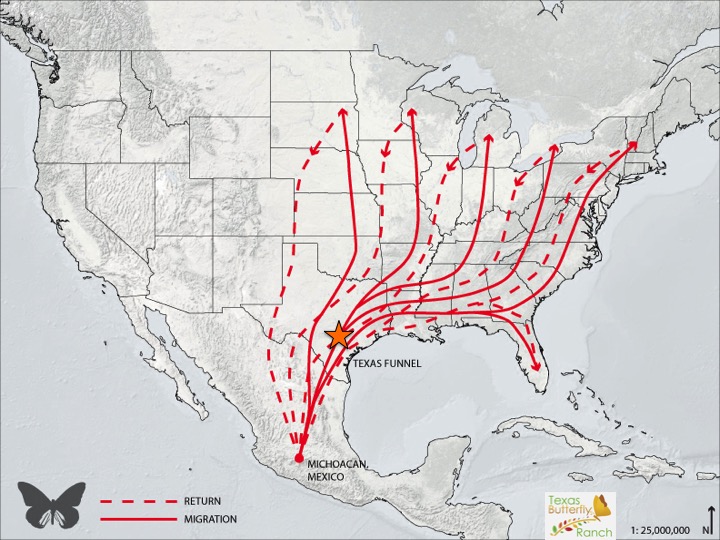

All migrating monarch butterflies pass through the Texas Funnel each fall. The migratory corridor plows through much of the Lone Star State and channels the insects into Mexico. That typically occurs during the last two weeks of October–right in time for San Antonio’s Monarch Butterfly and Pollinator Festival.

On August 30, Ontario lepidopterist Rick Cavasin cited “large numbers of monarchs” on the sand at Nickel Beach in Port Colborne on Lake Erie’s Canadian shore.

A few days later, Fred Kaluza, of Warren, Michigan, described a similar scenario. “A trip to Harsen’s Island in the St. Clair River today revealed hundreds of monarchs all bucking a headwind but southbound nonetheless,” Kaluza wrote.

By September 4, Jim Price in Wauwatosa, Wisconsin, reported the first roosts of the season had been spotted by his organization’s Friends of the Monarch Trail. One roost was estimted to include 1,500 monarchs. “Roosts have occurred each night so far, with the greatest numbers seen Monday night, impossible to count but several thousand by some estimates,” Price said via email.

Monarch butterflies east of the Rocky Mountains leave their roosts in Mexico in March and begin the multi-generation migration north over the summer. In early fall, successive generations head south to start the cycle anew, generally arriving in Mexico by the first week in November. Graphic by Nicolas Rivard.

Monarch butterfly scientist Chip Taylor, founder of Monarch Watch, wrote in a July 24 population status report that 2018 will be “another good season.”

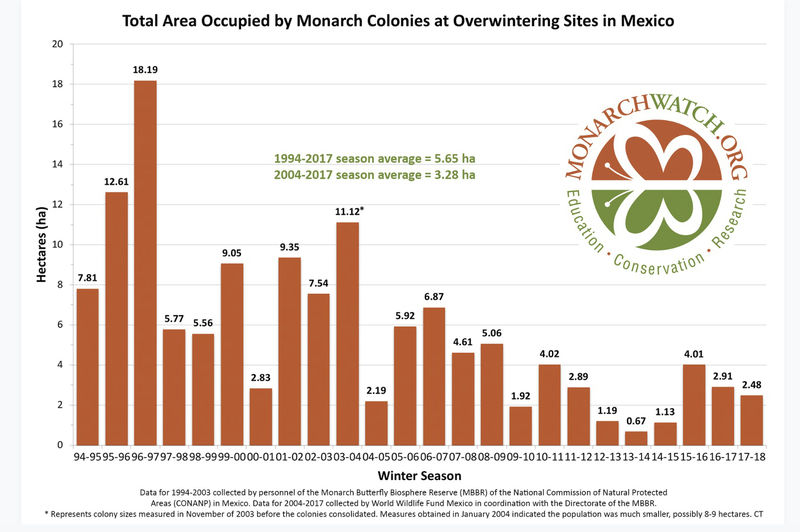

“Unless I’ve misjudged the situation once again, the migration should be the strongest since 2008 (a 5-hectare year) with the real possibility that the overwintering population could hit 5 hectares once again,” Taylor wrote.

For decades, scientists have determined the size of the migrating monarch butterfly population by counting the number of hectares/acres the butterflies occupy in their overwintering sites in the high altitude mountains of Mexico. From November through March, millions of butterflies roost in the sanctuaries. The more forest acreage they occupy, the larger and healthier the estimated population.

That methodology, developed in the late 1990s, is being challenged as recent studies suggest that focusing on the end game of the migration results in a misleading metric for determining overall monarch butterfly migration health.

“My first thought to this comment from Chip and others (about waiting to see what happens in Mexico) is that we don’t need to wait and see, because we already know that the monarchs are having a banner summer,” said University of Georgia ecologist Andy Davis via email.

Davis serves as editor of Animal Migration, an open access journal that publishes research on the biology of migratory species. He also oversees the über informative Monarch Science blog, which deciphers scientific studies for nonscientists. “The idea that the Mexico colony size will tell us how they are doing (or how they did this summer) is becoming more and more obsolete with the new studies coming in now.”

The studies to which Davis refers include recent papers like those written by Cornell chemical ecologist Anurag Agrawal, author of the award-winning Monarchs and Milkweed, a book that explains the complex relationships of the milkweed ecosystem.

The monarch population has been estimated for decades by measuring the amount of forest occupied by the overwintering insects in Mexico. Graphic via Monarch Watch

Agrawal challenged conventional wisdom in this 2016 paper, which suggested that availability of late season nectar plants, NOT the monarchs’ hostplant, milkweed, was among the most important factors in the continuation of the monarch butterfly migration. Generally, migrating monarchs suspend reproductive activities until the spring when they rouse in Mexico, thus they don’t require milkweed on which to lay eggs. Thus, providing “fuel” for their long journey to Mexico in the form of late season nectar is imperative.

In June, Agrawal reinforced the notion that the monarch conservation movement’s emphasis on milkweed is an oversimplification of the migration’s challenges, and likely misplaced.

Climate change, disease, and “the migration itself” are presented as the migration’s greatest obstacles in this paper in the journal Science. In it, Agrawal uses the 2017 season as an example of how a stellar summer doesn’t necessarily predict a spectacular overwintering population or subsequent robust numbers of spring migrants.

“This has been one of the biggest years for summer monarchs in the Northeast and Midwest that most folks can remember over the past 20 or so,” Agrawal said via email. “There was enough milkweed this summer. A huge number of butterflies–and the migration has begun. If the size of the overwintering population in Mexico is not much larger than the last couple of years, it would seem that something is wrong with the migration itself.”

“They are doing well up here, but beyond that I am unwilling to predict the future,” said monarch butterfly expert Karen Oberhauser, founder of Monarch Joint Venture and currently the director of the Arboretum in Madison, Wisconsin. “Too much can happen between now and December.”

NOTE: Oberhauser will join us for Butterflies without Borders: the Monarch Migration and our Changing Climate on October 19. Tickets available here.

A drought plagued much of Texas this summer, but serious rain events in Central Texas around July 4th, and then again Labor Day weekend, have set the stage for a successful nectar buffet in October. A recent visit to the Texas Hill Country suggests a welcoming setting for the migrating insects.

Goldenrod, late flowering boneset, hefty stands of Swamp milkweed, Asclepias incarnata, purple mist flower, Frostweed, and other late season flowers are just starting to produce blooms. With more rain in the forecast, butterfly arrivals should be well positioned to fuel up and continue their journey south to Mexico.

Related posts:

- Monarch Butterfly and Pollinator Festival 2018 to take place Oct. 19-21

- Five monarch butterflies tagged at Monarch Festival in San Antonio make it to Mexico

- Monarch Festival soars in San Antonio

- How to Tag a Monarch Butterfly in Six Easy Steps

- What does climate change mean for Monarch butterflies?

- New study: late season nectar plants more important than milkweed to Monarch migration

- Monarch butterflies head north as Mexican scientists try to move their forest

- Can’t get outside? Here’s how to track the Monarch migration from your desk

Like what you’re reading? Follow butterfly and native plant news at the Texas Butterfly Ranch. Sign up for email delivery in the righthand navigation bar of this page, like us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter, @monikam.

The following comments Monika in the above article are very important observations determining the monarch population.

“A drought plagued much of Texas this summer, but serious rain events in Central Texas around July 4th, and then again Labor Day weekend, have set the stage for a successful nectar buffet in October. A recent visit to the Texas Hill Country suggests a welcoming setting for the migrating insects.

Goldenrod, late flowering boneset, hefty stands of Swamp milkweed, Asclepias incarnata, purple mist flower, Frostweed, and other late season flowers are just starting to produce blooms. With more rain in the forecast, butterfly arrivals should be well positioned to fuel up and continue their journey south to Mexico.”

On the Yale campus in New Haven, Ct. as recent as the last seven days

there are still lots of monarchs flying around and yes many are laying eggs. From an unscientific opinion more than in years past. Here’s a short video demonstrating this https://youtu.be/T5m9GXN6xuA

It’s a proven fact the native nectar plants are in place on the landscape throughout the entire migration route as long as the percipitation occurs to produce the flowers and nectar to fuel the monarchs as is the case with every monarch migration. Monika and Karen are right what happens over the next 60 days pertaining to adequate percipitation along the entire route in a large part will determine The overwintering population. As Anurag explains in brief there’s plenty of milkweed and I would add for a much larger population. I guess all we can do is a rain dance.

Planted your milk weed seeds here in SC a few years ago an this year we are over run with caterpillars!! Have been bringing them through maturity successfully! Friends want seeds! How can I get more from you?

I live in Rule, TX (Haskell Co) where over the past 4 days (Sept 26-30) we have been seeing an incredible number of Monarchs passing through. At any time of the daylight hours I can go out and see 100+ butterflies on the flowers just outside my backdoor. During a recent drive (20180926) in the country I spotted one large area of roadside flowers where I would estimate the numbers in the 10s of thousands. And this was only one of several similar areas just along the roadside. Apparently these butterflies arrived right behind that last cold front that came through. We had north winds for over 24 hours.

I live in Lubbock have also noticed a bumper year over the past several days in around the city as well as in one of the local canyons (Ransom Canyon) as well as Crosbyton area (Crosby Co.): specifically Silver Falls Rest Area. At least 100 or more was observed by myself nectaring on Gayfeather and hanging in clumps in the understoried trees in both locations at Ransom Canyon and Silver Falls.

Monika,

There is no way a person can confuse Snouts with Monarchs. I am a long time wildlife photographer with lots of years photographing Monarch migrations. They are Monarchs you can rest assured!!!

My milkweed is suddenly covered in Queens, with a few Monarchs mixed in. I thought we had missed out this year. Maybe they were hanging back because of the rains? I’m in Austin, TX. and it is October 21st — a bit late? Today is our first good butterfly day.