One group of travelers not canceling their flight plans this spring: monarch butterflies.

That said, the migratory population currently heading north from their winter roosts in Mexico will be 53% smaller than last year.

The World Wildlife Fund Mexico (WWF) announced the disappointing news on Friday.

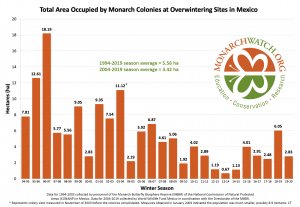

Conservationists calculate the monarch butterfly population by measuring the amount of forest occupied by the overwintering insects. According to Mexican officials at WWF and CONANP, the Mexican Commission on Biodiversity, the 11 colonies located this season covered 2.83 hectares–about seven acres. That number represents a 53.22% decrease from last year’s population estimate of 6.05 hectares, or about 15 acres.

Explanations for the decline vary.

Chip Taylor, founder of Monarch Watch, a citizen science organization devoted to the insects based at the University of Kansas at Lawrence, said in a recent blog post that despite a robust breeding season throughout the summer, monarchs experienced drought conditions in Texas and entering northeastern Mexico last fall. He speculated that the dry conditions and a late migration took a huge toll on the insects. He also noted that late season monarch butterflies sampled last fall in Kansas, “were both smaller than average and substantially below average in mass and thus ill-prepared to reach Mexico.”

Andy Davis, a migration studies expert at the Odum School of Ecology at the University of Georgia, believes “the migration itself is the weakest link” and a primary cause of declining monarch butterfly numbers. “That the migration is such a critical phase of the life cycle is something that I think a lot of folks, including scientists, have traditionally overlooked,” said Davis.

Keep an eye out for faded, migrant monarchs like this one spotted in 2019. Photo courtesy Lee Marlowe

Monarch butterfly expert Karen Oberhauser, in a special letter to members of Journey North, a citizen science organization that tracks wildlife migrations including monarchs, put the population drop in perspective.

“Saying that the population decreased 53% from last year is not very informative,” wrote Oberhauser, director of the University of Wisconsin Arboretum. She pointed out that the long-term average since the colonies were first measured is 5.62 hectares, while the mean for the past decade is 2.82 hectares, almost exactly what was measured this year. “Thus, 2019 was an average year for monarchs over the past decade.”

Oberhauser encouraged conservationists to continue creating pollinator habitat and to participate in citizen science programs.

The news hit hard in San Antonio, the nation’s first Monarch Butterfly Champion city, so named by the National Wildlife Foundation (NWF). In 2015, San Antonio became first in the country to commit to executing 24 action items identified by the NWF to increase pollinator habitat in cities along the IH-35 migratory corridor.

Texas has always been critically important to the monarch butterfly migration because of its location between the roosting grounds and the milkweed beds and nectar prairies that serve as host and fuel sources for the famous insects. Millions of monarchs pass through what’s known as the “Texas funnel” each spring and fall as they make their multi-generation migration from the Mexico to Canada and back. Spring in Texas is a critical time for the monarchs, as they seek out milkweed plants–their host and the only plant on which they will lay eggs and reproduce.

“Such disappointing population numbers!” said Cathy Downs, Conservation Specialist for Monarch Watch. Downs, who does educational presentations and workshops on monarchs in Texas from her base in Comfort, attributed the downturn to a late migration and drought last year.

“Double whammy, apparently, for overwintering mortality,” she said. Warmer weather takes a toll on the migrating insects, causing them to burn through fats they’ve built up migrating in the fall.

“It’s very disappointing to see such a significant decrease in their population size,” said Lee Marlowe, president of the San Antonio chapter of the Native Plant Society of Texas and ecological restorationist for the San Antonio River Authority. “This is a wake-up call for us to do what we can to conserve, protect, connect and enhance monarch habitat throughout their migratory pathway.”

Antelope horns milkweed, Asclepias asperula, near Comfort, Texas this week. Photo by Cathy Downs

Arriving butterflies should should find a bounty of wildflowers in Texas. The Ladybird Johnson Wildflower Center recently predicted an overall good season for 2020.

Much depends on weather. Recent rains bode well. A survey of local observers suggests milkweed, the monarchs’ host plant, is just starting to emerge from the soil.

Downs reported dozens of seedlings of two different milkweed species peeking from the earth in Comfort. “I’ve seen three worn and two fresh monarchs so far flying through and nectaring here- no eggs yet,” she said.

Monarchs have also been spotted along the San Antonio River and in neighborhood pollinator gardens.

“Monarchs in the yard today,” said Drake White, of the Nectar Bar, a local native landscaping company. “Worn ones, so the migration has started.”

TOP: Monarch butterflies flushing from Oyamel firs in Piedra Herrada sanctuary in the Mexican mountains, February 2020. Photo courtesy Veronica Prida.

Related posts:

- Entry to Mexico’s most popular monarch butterfly sanctuary should cost more than $2.77

- Enchanting trek includes monarch butterfly ‘rush hour’ at Piedra HErrada

- Dreamy visit to roosting sites results in rabies shots, credit card fraud

- ON the monarch butterfly trail in Mexico, “explosions,” joy, and hasta la vista en Texas

- We did it! San Antonio pollinator habitat hits 510 by 2020

- Cowpen daisy: Unofficial pollinator plant of the year 2019

- How to plan a successful butterfly garden

- Mostly native butterfly garden outperforms lawn every time

- A year in the life of an urban butterfly garden

- Downtown River walk plot converts to pollinator garden, creature haven

- Converting your Lawn to a Butterfly Garden

Like what you’re reading? Don’t miss a single post from the Texas Butterfly Ranch. Sign up for email delivery, like us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter, @monikam or Instagram.

Many monarchs stayed in the Houston area where my friends and I were scrounging to get milkweed to feed their cats. We were told not to do that, but what can one do when it’s too late for them to fly to Mexico. We can’t just let them die of starvation. Plus we never had a freeze so the survived the winter. When they reach a certain size on milkweed and we can’t get more, we feed them butternut squash.