Canadian zoologist Fred Urquhart and his wife Norah likely never imagined the practice of adhering of stickers to the wings of monarch butterflies they pioneered would evolve into the citizen science tagging program known as Monarch Watch which celebrates its 30th birthday this month. The couple first explored the initiative in 1937. It produced early citizen scientists, then known as “research associates,” and resolved a multi-decade quest to unravel the mystery of where monarchs overwinter each year.

The Urquharts’ tagging program launched from the University of Toronto in Ontario. It was introduced to a mass, national audience in a four-page spread in the May 1952 edition of Natural History Magazine titled “Marked Monarchs.”

There, on pages 226 – 229, the Urquharts invited readers to help track the monarch migration. They cast the butterflies as “mysterious travelers” that embarked on a transcontinental migration, from Canada through the U.S., down to Texas and unknown points south. The migration posed a massive puzzle. Where did they go? Did they fly independently or in groups? Did they return to their breeding grounds?

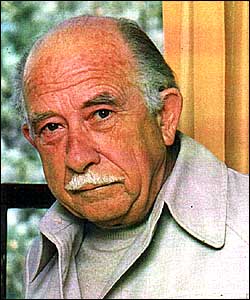

Dr. Fred Urquhart, 1911- 2002 — Photo courtesy Monarch Watch

The article invited those interested to become “butterfly banders.” It suggested they send a letter to Toronto and request “tags,” specialized stickers for tracking the butterflies. Bird banding had been underway for centuries, but tagging butterflies and tracking their movement had yet to enter the research arsenal—until now.

Fred Urquhart struggled for decades to perfect a gummed label that would stick and stay on a butterfly’s wing. Much of the challenge resulted from the irregular surface on which the tag was placed—a tiny patch of thousands of butterfly scales that created an unwelcoming surface for adhesives. The glue and tag stock required durability in wind, rain, and wild temperature swings over many months. The tag also required a serial number and instructions for returning it and the specimen, if found, to scientists. It had to be safe for the butterflies, not inhibit their natural flight, and be relatively easy to apply.

Combinations of paper, inks and adhesives (some of which turned out to be toxic) preceded the alar tags of today, which slip onto a monarch wing with the flick of a fingernail and light pressure. At one point, the Urquharts utilized a tag that had to be applied with glue, which was cumbersome, water-soluble and short lived. Later, adhesives similar to postage stamps that had to be moistened to stick were tapped. Those failed, too.

Finally, the team in Toronto figured out “a most successful method,” according to the article. Its success relied entirely on the tag’s application, which seems barbaric today, given the ubiquity of self-adhesive stickers on everything from fresh fruit to windshields.

Article in the May 1952 edition of Natural History Magazine in which the Urquharts suggested their tagging method. File photo

“Punch a hole in the wing of the butterfly with a paper punch,” the articled advised. “Over this hole, which was made immediately behind the stout marginal vein of the wing, place a tiny white paper label….”

Directions for folding the gummed label over the outer edge of the butterfly’s forewing so the glue would adhere to the tag through the opening, followed.

More than 40 years later, as Fred and Norah Urquhart, ages 83 and 74 respectively, announced the cessation of their tagging initiative, Orley “Chip” Taylor, a 56-year-old entomologist at the University of Kansas at Lawrence, took up their cause and launched Monarch Watch. The citizen science tagging program operates in the prime monarch butterfly summer breeding grounds of the American Midwest.

Taylor started the organization as an experiment. In 1992, he tapped Brad Williamson, a teacher at Olathe East High School about 30 miles east of the University. That first year, Williamson produced the tags on a printer, then he and Taylor would meet at a McDonald’s franchise about half way between Olathe and Lawrence where Williamson would hand over the tags.

Together, Taylor and Williamson engaged 500 adults and 4,000 children to tag an estimated 5-6,000 butterflies that first season. The pilot program used the Urquhart glue-based system of applying tags to the leading edge of the butterflies’ forewing.

Like his predecessor, Taylor struggled with the tags. Legible, durable, practical tags that would cling to a butterfly through dry, wet, hot and cold over many months eluded him for years. From 1992 until 1998, the program used the Urquharts’ method. In an April 1994 newsletter to volunteers, Taylor mentioned that tagging kits would include 20 tags, instructions and a “vial of adhesive for tag application.” Tags were sent free of charge to “collaborators,” the word Taylor used in place of Urquhart’s “research associates.”

Monarch Watch founder Chip Taylor on the Llano River in the Texas Hill Country in 2012 — File photo

The glue and tag system was cumbersome and imperfect. No matter how explicit the instructions, collaborators used too much glue, affixing butterflies to their fingers or the lawn furniture, gluing wings together, and sometimes seriously damaging the butterflies in the process.

Jenny Singleton, who continues to tag monarchs in Menard, Texas, started tagging in 1995 and used the glue method. She received a vial resembling a fingernail polish bottle in the mail along with her tags. “It was a mess,” she recalled. And recovery rates were miniscule because butterflies were often damaged or the tags fell off.

Taylor knew the tagging system had to change, thus he and his team continued to experiment. They tried rectangular tags for a while–but the corners kept curling and falling off. Eventually, Taylor contacted Watson Label Co. in St. Louis, Missouri, to see about developing a durable tag that was easy-to-adhere.

An estimated 200,000 tags are sold by Monarch Watch annually. –Photo by Monika Maeckle

Taylor discussed adhesives with Wayne Roth, a senior sales rep in the industrial tape and specialties division at Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing Company in St. Louis, the company that would later become 3M Corporation. Roth was intrigued. The glue had to be thick enough to seep through a layer of scales and stick to the wings. It couldn’t be toxic. It required a special die-cut, and would need to peel off easily from its sheet. Each tag would also require a unique code, number and University of Kansas imprint.

“Not a trivial technology in any way,” Taylor said later.

The 3M team collaborated with Watson Label Company and chose adhesive number 9442 because of its durability. Following several trials, Monarch Watch settled on the tag used today: a circular, white polypropylene dot, printed on all weather-stock with permanent ink. The tags, printed on four- by five-inch sheets and sent by mail with detailed instructions each August, measure .89 centimeters in diameter and weigh less than .01 of a gram.

Today, Monarch Watch distributes about 200,000 tags annually. Monarch Watch staff estimate that only about half or fewer of the tags are used to each year. The number of tags recovered in Mexico annually ranges from 300-900. Since 1992, volunteers have tagged more than 2.2 million monarchs, while more than 19,000 of the tags have been recovered. The overall recovery rate is just under 1%. In 2019, the codes used to individualize each tag, expanded from a three-letter, three-digit tag to a four-letter, three-digit tag, because “we ran out of numbers,” said Taylor.

Tags cost $15 for 25, $50 for 200.

Until 2015, taggers could search their name on the recovery database and easily determine if one of their butterflies had made it to Mexico. But Monarch Watch has changed the system in recent years to “clean up the data,” said Taylor.

Now, only tag numbers, recovery sites and the year tagged are posted for recoveries. The database changes were necessary, said Taylor, given the difficulty of cross checking more than two million records, many of which are handwritten. The organization started making digital spreadsheets available for data entry in 2012. But much of that data continues to be returned on paper and must be transcribed. Social media and email have moved to fill in the gap of identifying recovered tags.

“We have a 15-foot wall of data books,” said Taylor, describing the abundance of records that are in the process of being validated by the Monarch Watch team. He said it’s taken three years to validate the accuracy of the data with an estimated 10% error rate.

Monarch Watch celebrates its 30th birthday this year and has introduced Iphone and Android phone apps to supplement traditional data collection. “Type in Monarch community science or monarch tagging,” said Taylor. The organization will commemorate its three decades with a gala on September 15 followed by a weekend of activities. Details here.

TOP PHOTO: Kati Singleton shows off an historic monarch tag in an undated photo. –Photo courtesy Jenny Singleton

Want to tag some monarch this season? Join us at Brackenridge Park in San Antonio on October 8. Details at link above.

Related posts:

- Founder of the monarch butterfly roosting sites lives a quiet life in Austin, Texas

- How to tag a monarch butterfly in six easy steps

- Two monarch butterflies tagged on the Llano River in Mexico recovered in Mexico

- They’re here! Drought conditions greet monarch butterflies as they arrive in Texas

- Save the date: 2022 Monarch Butterfly and Pollinator Festival to take flight at Brackenridge Park

- Massive arrivals of monarch butterflies in the Texas Hill Country signal 2021 migration is on

- Courtship flights, late departures define recent visit to Piedra HErrada sanctuary

Like what you’re reading? Don’t miss a single post from the Texas Butterfly Ranch. Sign up for email delivery, like us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter, @monikam or Instagram.

Great story!

Thanks for reading and writing! —MM

Does this hurt the monarch

The Urquhart tag system had been perfected way back in the mid-1950’s and did not require punching a hole in the wing with a paper punch. The system was used by the Cape May Monarch Monitoring project in the 1990’s and 2000’s and yielded these impressive recapture results.

Fascinating article! Thank you!

Thank you for reading and writing. –MM

Yeah, crazy how complicated the tags were to create. –MM