A small community of devoted commercial butterfly breeders is bracing for the devastating impact that the listing of the monarch butterfly as “threatened” under the Endangered Species Act will have on their industry.

And yes, it’s an industry–one that touts monarch butterflies as its biggest cash crop. Professional butterfly breeders raise lepidoptera for sale, shipment and profit, typically $6-$10 a piece, plus shipping and handling. That’s how butterfly houses at museums and zoos, butterfly releases at weddings and funerals, and caterpillar condos for schools and festivals, all are made possible.

It’s no simple undertaking. The USDA regulates the industry, and requires permits for any of the nine butterfly species legally allowed to be shipped across state lines. Not all states allow all nine species. The cleanliness and safety protocols for raising healthy butterflies are significant. Meeting deadlines for weddings and festivals is stressful.

As I write in my book, The Monarch Butterfly Migration Its Rise and Fall, a lack of host plant, disease, predator invasions, poor planning, bad weather, or simply bad luck can ruin an order. For a time many years ago, I wanted to become a butterfly breeder. When I learned what it takes to do it right, I decided to stick to insect advocacy.

The ESA listing as proposed would allow the rearing and annual sale of only 250 monarch butterflies by any individual. Shipping them would be illegal. The 90-day public comment period began December 12, 2024 and continues through March 12, 2025. After that, USFWS will review comments and consider new information and develop a final ruling within one year.

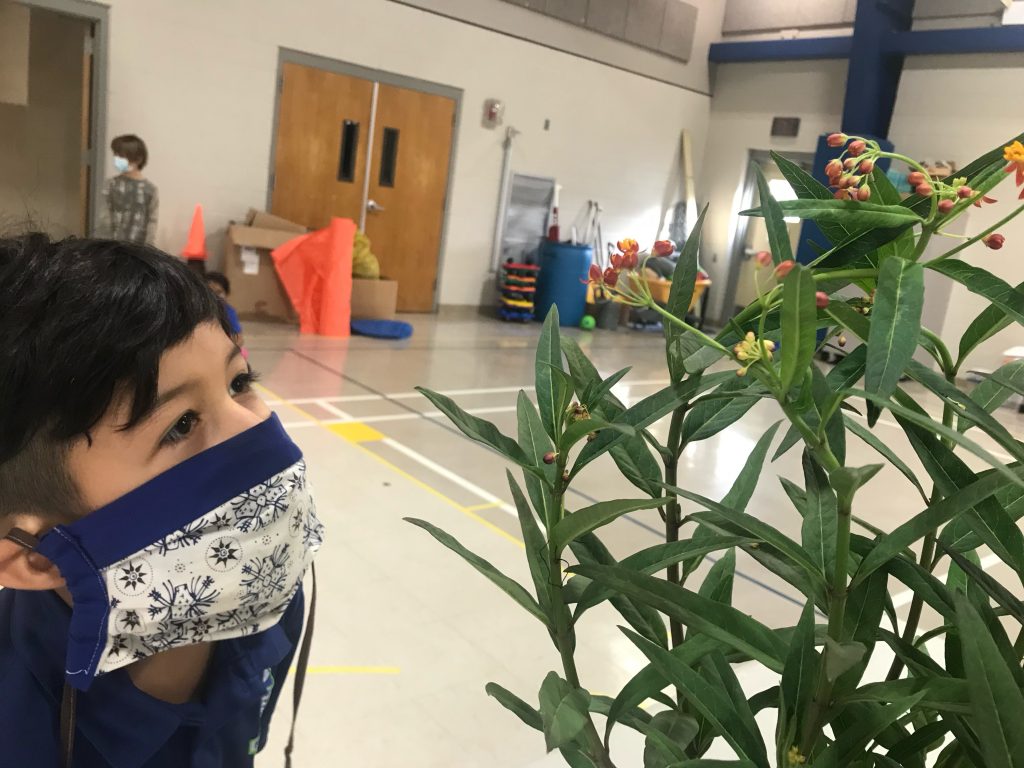

This kind of experience could go extinct: a child engages with a monarch butterfly at San Antonio’s Monarch Butterfly and Pollinator Festival. –Photo by Drake White

So how big of a hit will the commercial butterfly breeding business take when the monarch is listed as “threatened”?

“It’s massive. Millions and millions. Not just the cost of the butterflies,” said Kathy Marshburn, executive director for the International Butterfly Breeders Association (IBBA). Incorporated in 1998, the trade association represents the interests of some 60-plus small businesses in the U.S. and Puerto Rico. Its mission: “Promote, educate, and protect the butterfly farming industry through education, sharing of evidence-based rearing methods, conservation, and political action.”

“If a city is putting on an event, there’s other sources of income that are going to be impacted and lost,” she added. According to Marshburn, for most professional breeders, monarch butterflies represent half or more of their livestock sales. For some breeders, it’s much more.

SkyRiver Butterflies in northern California, is the largest traveling butterfly exhibitor in the world based on attendance, according to its founder John Daily. The company organizes and tours dozens of butterfly exhibits year round, all over the U.S. While most of the exhibits feature exotic butterflies, Daily said when the monarch is listed and the rules go into effect, he will be forced to shut down his two native butterfly exhibits that feature monarchs. That loss, $150,000-$180,000 per year, represents about 20% of his business.

“U.S. Fish and Wildlife Services’ level of ignorance is breathtaking at this point,” said Daily. “They say it’s based on the science but it’s absolutely not based on practical application.”

Commercial butterfly breeders ship monarch butterflies in glassine envelopes and packed with ice. –Photo by Monika Maeckle

Daily and other breeders question allowing amateurs with no training or protocols to breed 250 monarch butterflies annually, releasing potentially unhealthy butterflies into the gene pool and infecting them with diseases like Ophryocystis elektroscirrha, known as OE, the monarch-centric, spore-driven disease that is spreading, especially in warmer climates. Professionals go to extreme lengths to follow sanitation protocols and best practices to avoid disease. Their livelihoods depend on it.

Connie Hodsdon of Flutterby Gardens in Manatee, Florida, said monarchs make up 95% of her business. “I’ll be standing in the unemployment line when the listing comes down,” said Hodson, who started the business in 2001. Since then, she has provided tens of thousands of butterflies to museums, weddings, funerals and festivals.

Monarch Watch tag on monarch butterfly. —Photo by Monika Maeckle

Hodsdon trains others how to raise healthy butterflies as leader of education at the IBBA. At public meetings staged by USFWS and broadcast on YouTube this week, she joined Daily in questioning why USFWS would trust hobbyists to raise healthy butterflies, rather than professionals who have a financial stake in butterfly rearing.

Another consideration is the unique charisma monarch butterflies display. Marshburn noted the universal appeal of the iconic orange-and-black creatures, an effective tool for sparking curiosity and care about nature, especially with children.

“If the human nature connection that you make with that butterfly is not there, do you look at a powerpoint or a picture? Do you have the same impact? I’ve had parents say, ‘we never see butterflies because we live in the city.’ If they have no butterflies, what happens?”

At Monarch Watch, the monarch butterfly conservation organization based at the University of Kansas in Lawrence, KS, director Kristen Baum said the nonprofit will stay the course of its existing programs until details of the final ruling have been established.

Since 1993, Monarch Watch has encouraged the human interaction of physically tagging monarch butterflies in the interest of science, which has resulted in data that has helped scientists decipher the insects’ migratory habits and population status. Monarch Watch also has reared butterflies and caterpillars, making them available for a fee to educational organizations.

“We aren’t making changes to our programs at this point, but we will evaluate options if needed depending on what exemptions for education and research are provided in the final rule,” said Baum via email. She pointed out that currently, the USFWS rule allows for individuals to tag only 250 monarchs (wild or raised) per year. If that were the case, “That could limit tagging efforts,” she said.

Caterpillar condo at a San Antonio school in 2020. –Photo by Ashley Bird

Ashley Bird, director of San Antonio’s Monarch Butterfly and Pollinator Festival, agrees that the human connection with monarch butterflies is a powerful engagement tool. Since its founding by the Texas Butterfly Ranch in 2016, the Festival has ordered thousands of butterflies for service in monarch tagging demos, butterfly releases and as teaching tools in the classroom.

The loss of monarchs as public servants at community events will definitely be felt, but that loss will not be insurmountable, Bird said.

“Not having access to caterpillars will be a great loss,” she said, referring to the Festival’s wildly popular caterpillar condo program, which makes monarch caterpillars and milkweed plants available in pop-up cages to Title 1 schools as part of a hands-on learning exercise. Bird has purchased caterpillars in the past from both Monarch Watch and butterflies from Hodsdon’s Flutterby Gardens. “It pushes us on the education side to be more creative about how we present monarchs.”

For historical context on the monarch and how we got here, check out my book. It’s a natural history of the monarch migration from 1976 to the present.

Currently the listing continues to be under review as public comments accumulate online. As of this writing, more than 9,100 comments have been posted, the vast majority of which appear to support the listing. For more information, check out these useful links that address FAQs about the current rule, and the potential 4D rule (exceptions and amendments).

TOP PHOTO: Monarch butterfly releases at Festivals and other events will be less possible if commercial breeders are put out of business. –Photo by Matt Buikemi

Related articles

- Monarch butterflies listed as “threatened” under the Endangered Species Act

- A tense online debate: raising monarch butterflies at home

- New study: monarch migration at risk, monarch butterflies are not

- USFWS rules monarch butterflies worthy of protection, but they don’t have resources to protect it

- As ESA listing looms, new study challenges dogmatic narrative that monarchs are in decline,

- “Weird” weather has scientists concerned about this year’s monarch butterfly migration.

- Declining monarch butterflies: Mexico population drops 59%, West coast population down 30%

- Recent IUCN “endangered” listing creates confusion for monarch butterfly fans

- IUCN revises listing of monarch butterfly from “endangered” to “vulnerable”

- Endangered Species Act: wrong tool for monarch butterfly conservation?

- USFWS gets three more years to evaluate monarch butterfly ESA status

Monika – as I stated to you I- you have taken my quote out of context- please

Correct it. I do not believe fish and wildlife are ignorant. What I believe is they do not understand the relationship between the butterfly industry and conservation and how key that relationship is. .

HI John,

I kind of got into that pretty deep in the article, but feel free to expand on your viewpoint. Thanks for writing. –MM