Monarch butterfly numbers hit dramatic lows this season, with the the eastern migratory population at the overwintering sites in Mexico plummeting 59%–the second lowest count in history, officials announced February 7. The week prior, researchers reported the California population dropped 30%.

Climate change was named the biggest factor in causing the losses, along with the usual culprits of pesticide use, habitat loss, and illegal logging at the roosting sites in Mexico.

In the eastern population, which funnels up and down the IH-35 corridor from Mexico to Canada and back, the butterflies endured an untimely 2023 spring freeze in Texas that stunted the availability of milkweeds, the host plant on which they lay their eggs. The cold weather also stunted the usual spring wildflowers that provide nectar and fuel for the insects.

In the fall, the butterflies suffered an historic hot, dry summer that left much of Texas and northern Mexico parched, dashing their ability to fuel up on nectar to build their fat stores for overwintering.

Texas is often labeled the most important state in the butterflies’ multi-generation migration because it is the first and last stop on their long journeys from Mexico to Canada and back each year.

Monarchs and other pollinators need late season nectar plants for fuel. Here, a monarch rests on Frostweed on the Llano River. Photo by Monika Maeckle

In California, the iconic insects appeared to rebound in late fall, but then multiple extreme weather events conspired to undermine their success.

“Climate change is making things harder for a lot of wildlife species, and monarchs are no exception,” said Emma Pelton, a monarch conservation biologist at the Xerces Society, the invertebrate conservation organization based in Portland, Oregon.

Pelton spoke to ABC News on January 30 regarding the western monarchs’ decline. “We know that the severe storms seen in California last winter, the atmospheric rivers back to back, are linked at some level to our changing climate.”

While scientists reacted to the announcements with statements of reassurance, some monarch conservation nonprofits were quick to pounce on fundraising opportunities with “save the monarchs” and “donate now” messaging.

“This count does not signal the end of the monarch butterfly migration,” said Chip Taylor in a Q & A on the Monarch Watch blog.

Taylor, the founder of the citizen science organization that tags monarchs each fall and promotes various pollinator conservation efforts, conceded the news came as “a shock” and labeled this season’s demise as concerning, but expressed confidence in the butterflies’ resilience.

“Catastrophic mortality due to extreme weather events is part of their history,” Taylor wrote in the February 7th post. “The numbers have been low many times in the past and have recovered, and they will again. Monarchs are resilient.”

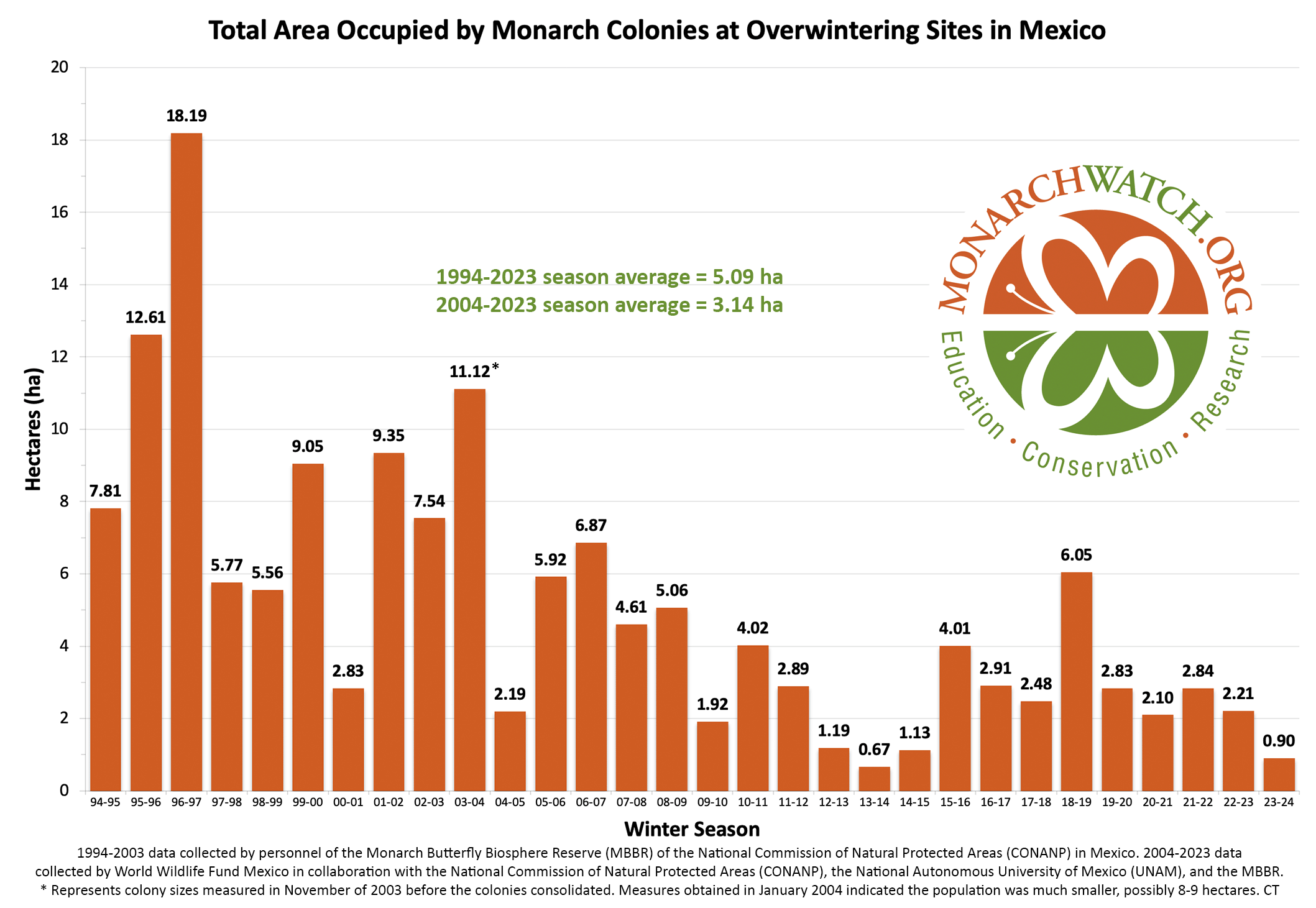

The 2023 eastern population of migratory monarch butterflies occupied only 2.2 hectares/5.46 acres of the Mexican forest where they traditionally overwinter, a press release issued by the World Wildlife Foundation noted. In 2022, the butterflies populated 5.5 acres/13.59 acres.

Experts measure the area of forest in which monarch butterflies hibernate each winter, providing a scientific indicator of their population status.

Contrarian scientist Andy Davis, a migration studies expert at the University of Georgia’s Odum School of Ecology, was quick to challenge the negative news.

On his Thoughtful Monarch Facebook page, Davis wrote the following:

Davis has long contended that using the population size of monarch butterflies that end up in Mexico as the primary indicator of the insects’ overall health is a misguided approach–kind of like judging the success of a marathon race not by the number of runners who start, but only by the number of those who finish.

“I’m not diminishing the validity of the winter colony data, only pointing out that they are not an indication of how the population is doing, despite what some seem to think,” Davis wrote. He added that every time the bad news about monarchs comes to light, “everyone freaks out and rushes to the nursery to buy more tropical milkweed, or they ramp up their home rearing efforts, etc. I see big conservation groups using these announcements to beef up their donations, or get publicity.”

Nonprofit organizations often pounce on fundraising opportunities when bad monarch news hits the press. Screenshot via Xerces Society web page

The tandem negative news reports may impact this year’s U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service review, which considers the monarch for listing under the Endangered Species Act.

The 2015 petition requesting “threatened” status submitted by the Xerces Society and others was finally ruled on in 2020. USFWS ruled that listing the monarchs was “warranted but precluded.” In other words, the butterfly was moved into the queue as an official candidate for ESA listing but regulatory initiatives were not activated because the agency had “higher priority listing actions.” Instead, the monarch’s status will be reevaluated annually.

Since, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature added, then removed, monarchs from its Red List of Endangered Species, Canada has listed the monarch as endangered, and the state of California has invoked a “do not touch” rule regarding monarchs. In the Golden State, it is against the law to touch or handle monarch butterflies unless the individual doing so has a permit.

Scott Black, executive director of the Xerces Society, thinks the insects should be listed.

“I am very concerned with the monarch numbers out of Mexico this year,” Black shared recently in a Xerces press release. “We need to move forward on listing monarchs under the Endangered Species Act in the U.S., to maximize protection and restoration of habitat across the monarch’s range and take action to protect these animals from toxic pesticides.”

An ESA monarch listing review by USFWS is expected by the end of this year.

TOP PHOTO: Monarch butterflies take to the skies at Cerro Pelón n March, 2011 –Monika Maeckle

Related articles

- US Fish and Wildlife Service rules monarch butterflies worthy of protection, but doesn’t have resources to provide it

- Recent IUCN “endangered” listing creates confsion for monarch butterfly fans

- IUCN revises listing of monarch butterfly from “endangered” to “vulnerable”

- AS ESA listing looms, new study challenges dogmatic narrative that monarchs are in decline,

- Q&A: Migration expert Andy Davis says for monarchs it’s survival of the biggest

- Happy 50th Earth Day: Monarch butterflies enjoy a win of sorts

- Endangered Species Act: wrong tool for monarch butterfly conservation?

- USFWS gets three more years to evaluate monarch butterfly ESA status

- Founder of the monarch butterfly roosting sites lives a quiet life in Austin, Texas

- Entry to Mexico’s most popular monarch butterfly preserve should cost more than $2.77

- How to plan a successful butterfly garden

The trouble with “the butterflies are probably suffering more mortality during the fall migration” hypothesis is that we can already tell, at the start of the migration in the upper Midwest and Great Lakes region, whether or not the fall migration will be big, small or average sized. We can make this judgement based on the multitude of observations posted on iNaturalist and Journey North in late August and September, e.g. the “fall roost” reports. Based on these observations, I publicly predicted a 30-50% decline for California (actual was 30%) and a 35-50% decline for Mexico (actual was 59%).

I live in the San Francisco area..I have enjoyed the Monarchs all last year.

Life finds a way! Have faith! The Monarchs do!

Climate change is a BIG LIE, scientist have proven this!!!