The dreaded oleander aphids have arrived here and are trying to wreak havoc in my gardens. At a friend’s house today, I noticed that all of her milkweed is infested beyond hope….Are there any new ideas on how to deal with them? Thanks.

Jan LeVesque is not alone in her exasperation at the hands–rather, mouth parts–of plant sucking aphids. Anyone who raises milkweed in an effort to attract Monarchs is familiar with the soft-bodied, squishy orange insects that seemingly take over anything in the Asclepias family.

Jan, like many before and after her, posted the above query on the Monarch Watch DPLEX list, an old school listserv that goes to hundreds of citizen and professional scientists and butterfly fans who follow the Monarch migration. And as usual, the community had plenty of ideas.

But before we explore how to kill them, let’s take a look at the interesting life cycle of these ubiquitous, annoying insects, known as oleander aphids, milkweed aphids, or by their Latin name, Aphis nerii.

First off, they are parthenogenic, which means they clone themselves and don’t require mates to reproduce. In addition, the clones they produce are always female. Yes, that’s right–all girls. “No boys allowed.”

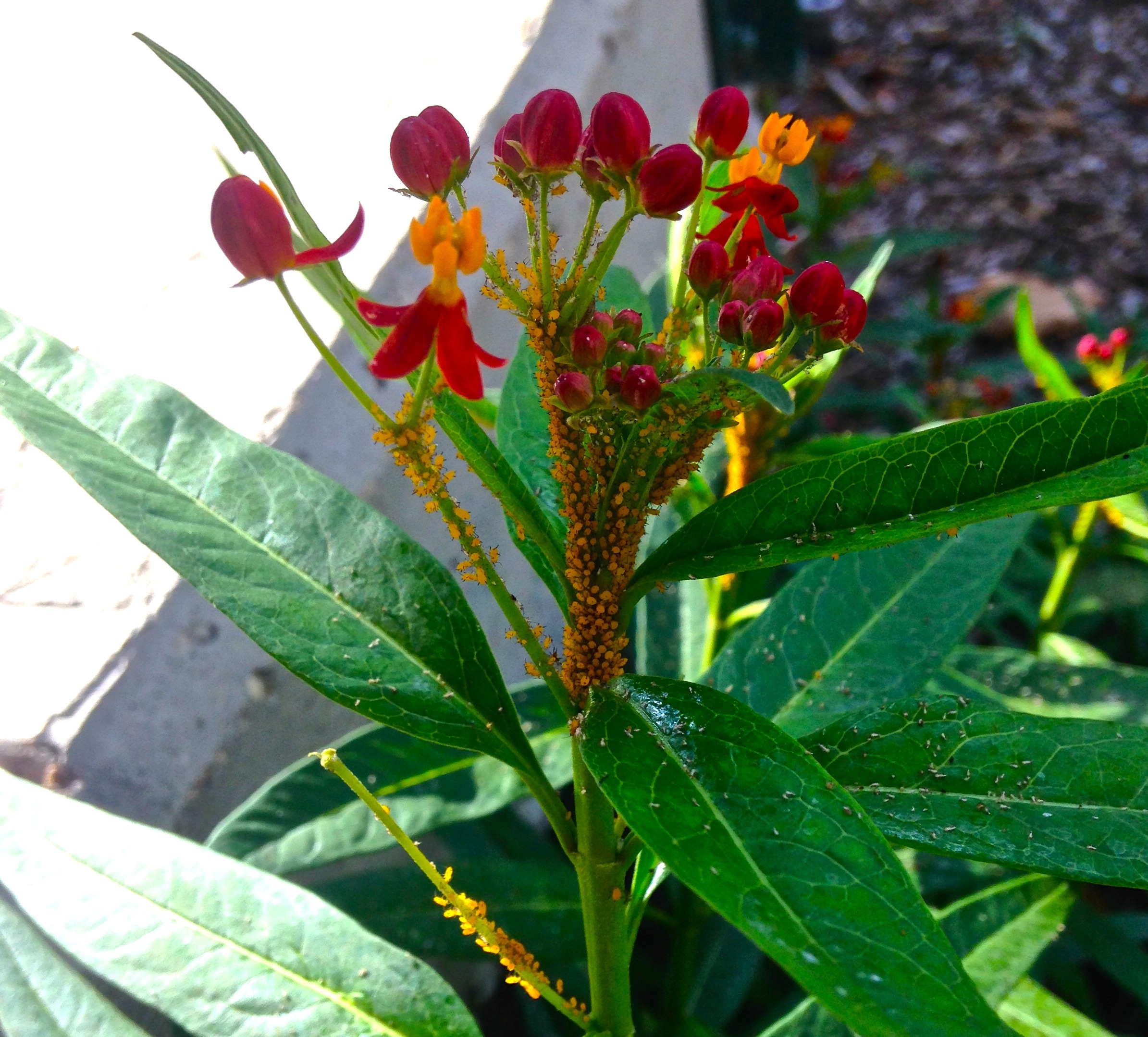

If you raise milkweed and Monarchs, you’re well acquainted with oleander aphids. Here they are on Tropical milkweed. Note the sticky, slick looking substance on the leaves. That’s honeydew. Photo by Monika Maeckle

All female aphid colonies undermine our milkweeds. Photo via University of Florida

According to the University of Florida’s Department of Entomology and Nematology “Featured Creatures” website, “The adult aphids are all female and males do not occur in the wild.” Instead, the aphid moms deposit their all-female nymph broods on the stalks of our milkweed plants. That generation morphs four more times until they grow up to become aphid moms who repeat the process.

Even more interesting, under normal conditions, adult female aphids do not sport wings, but get this: if conditions are crowded, or the plant is old and unappetizing (which happens as the summer progresses in our part of the world), the girls grow wings so they can fly away to greener pastures–or in this case, fresher milkweed. Aphids live 25 days and produce about 80 nymphs each.

This brilliantly efficient method of reproduction, says Featured Creatures, is one of the reasons “large colonies of oleander aphids…build quickly on infested plants.”

Small populations of aphids are pretty harmless to the plants, but when you get a large colony, the milkweed suffers. The aphids insert their piercing mouthparts into the milkweed, literally sucking the life out of it as they enjoy the sweet liquid that courses through the plant. The high concentration of sugar in that liquid means the aphids have to eat a lot of it to get the protein they need.

That results in a profuse amount of excrement, called honeydew. It is prolific and forms a thin, sticky layer on the leaves of your milkweed, choking the absorption of essential nutrients. It can also cause sooty mold, an ugly dark fungi that can cover your milkweed.

We have a fair amount of milkweed near the house and it’s been aphid free so far – except for one incarnata shoot on which a 3 inch long colony had formed with probably more than 500 aphids of all sizes. Not having mixed up any fancy aphid remedy and not having insecticidal soap, I looked under the sink for the handy spray bottle of 409. It wasn’t there – so, I grabbed the Windex instead. Last evening a quick inspection showed that all the aphids were blackened and dead. I checked again this morning and spotted one aphid. The plant seems unaffected by the treatment.

Once you have well-established infestation of aphids, the plant just goes downhill. The aphids themselves are also highly appetizing to Ladybugs, wasps and syrphid flies–all insects that eat aphids and Monarch or Queen eggs with equal abandon.

When I get a serious aphid infestation, I typically use a high pressure spray of water to blow the bugs off the plant. That simultaneously washes the honeydew off the milkweed, which will deter the arrival of ants and also clean the leaves so they can absorb sun, air, water and nutrients to fuel their growth.

My other method is to simply squish the aphids between my thumb and fingers and wipe them off the plant. Your thumb and fingers will turn bright gold, but will wash off.

Some gardeners like to use alcohol or other additives with the water spray, but I prefer to keep that stuff off my plants.

A Ladybug’s favorite treat: aphids. Photo by Monika Maeckle

As Dr. Karen Oberhauser of the University of Minnesota and founder of the Monarch Larvae Monitoring Project wrote to the DPLEX list in July of 2015, “Detergent treatments will kill any live insects on aphid-infested plants, including Monarch eggs, Monarch larvae, and aphid predators like syrphid fly larvae, ladybug larvae, and lacewing larvae.”

Alas, even Dr. Oberhauser, who has decades of experience with aphids, admits “There is really no good way to kill aphids without killing everything else, except by trying to lower the population by carefully killing them by hand.”

If Monarch cats are not present, I spray with insecticidal soap and then rinse later with water hose. If that is ineffective, I move up to Neem oil and rinse it off also later. One and/or the other are very effective…. It is easy to go from 1 to 1,000s of aphids in a very short period of time.

Another option is biological control. Lady beetles or Ladybugs feed primarily on aphids. Somehow they seem to magically find their way to our milkweed gardens to feast on the yellow critters. Ladybugs can be purchased in bags at some garden centers and released to do their jobs. But remember–they also eat butterfly eggs.

Hover flies and wasps also eat aphids. Wasps have a bizarre practice of laying their eggs on the aphids, then eating them from the inside out, leaving a brown shelled carcass in their wake. We often find these hollow corpses on our milkweed plants.

One good thing about aphids: if you see them on a plant in a nursery, you know the milkweed is clean, and has NOT been sprayed with systemic pesticides. We all want perfect looking plants, but the occasional aphid is a good sign that your plants are pure. See this post for more on that topic.

Need more ideas for getting rid of aphids? Check out this useful post from The Monarch Butterfly Garden. If you have new tips not covered here, please leave a comment below. Good luck!

Related Articles

- Guidance on milkweed management confuses butterlfy gardeners

- Late season Monarchs create gardening quandary

- What to do with late season Monarchs

- MIghty Monarchs brave south winds, Hurricane Patricia, to arrive in Mexico

- Desperately Seeking Milkweed: Monarch Caterpillars Appetites Create Milkweed Emergency

- Butterfly Farmer Edith Smith Keeps it All in the Family at Shady Oak Butterfly Farm

- How to Raise Monarch Butterflies at Home

- Part II: More Tips on Raising Monarch Caterpillars and Butterflies at Home

- Tropical Milkweed: To Plant it or Not is No Simple Question

- Oh Those Crazy Chrysalises: Caterpillars in Surprising Places

- Butterfly FAQ: Is it OK to Move a Chrysalis? Yes, and here’s how to do it

- Should You Bring in a Late Season Caterpillar into Your Home?

Pesticides will kill aphids, but they often remain in the plant for months and will also kill Monarch caterpillars. Photo by Sharon Sander

Like what you’re reading? Don’t miss a single article from the Texas Butterfly Ranch. Sign up for email delivery at the bottom of this page, like us on Facebook, follow us on Twitter, @monikam or on Instagram.

Hi,

Thanks for the post! I’ve followed your blog for quite some time and always enjoy reading your articles.

One bit of caution on buying ladybugs-the ladybugs that are sold in garden centers are Asian ladybugs. These become invasive and take the place of the native ladybird beetles.

Check out this great site that I’ve used in my classes in the past.

http://www.lostladybug.org/

Thanks again for your informative blog!

I like the smash and scrap away method. That way I control what I am killing. This year in north eastern Missouri has been a weird weather year and either it was too wet or too hot and the milkweeds did not do well. Also, we have not had many mosquitos or aphids or milkweed bugs.

I have been using a plastic baggie. Knock the milkweed bugs into it and skish.

why can I not pin these articles on pinterest to save them?????????? FRUSTRATING!

I use scotch tape or masking tape to remove aphids from my milkweed plants. The aphids easily stick to the tape, which does not hurt the plants. Then I fold the tape over and throw it away. If you do this every few days in your garden, you won’t have that many aphids overall.

Great idea! Hadn’t heard that one. Thanks for sharing. –MM

Fantastic idea. Just cleared out the whole bunch in only a few minutes. Thanks!

Just did it! What an excellent suggestion, thank you thank you!!

Hello, I have found an extremely large cocoon attached to the outside brick of my house. It’s high up above rose bushes. Any idea what it may be? I’d like to try and include a photo. Description: soft, threadlike fibers, approx. 3″x4″, square, off white. I live in Dallas, Texas.

Impossible to guess without a photo.

I do not know how to attach a photo here. If you will please contact me thru my email, I will gladly include a photo in response to you.

tkhouw@tx.rr.com

Teresa,

That size could indicate a luna moth. Gorgeous insect.

I tried hydrogen peroxide because I had a small spray bottle at hand. It killed them but I don’t know about the lasting effect.

Has anyone tried diatomaceous earth? Wet or dry method. My theory is it should work…but think I need to add a wetting agent/dish soap. Does not seem to be working fast enough for me.

I’ve had success with the squashing by hand method. I started doing this several weeks ago, and not only are aphids now rare on my milkweed, the plants themselves have recovered, and have become lush and full. The trick is that you have to do this a couple of times a day, whenever you see a cluster (or even one aphid). Eventually, there will be fewer and fewer aphids. I really have to hunt for them now.

Hello, I just found this article. I was not actively growing milkweed, however I now have two good sections of plants. I have never noticed the bright orange aphids till this year. The black blight is in a patch on the ground and then I noticed the aphids. So I didn’t have them when they were blooming but now in the fall they are spreading very fast, in very large numbers. I’m in Southern Ontario and we had a very long wet summer with a short heat wave this past week. The pods are being sucked dry. I hand squished and drowned some of them and I guess will continue with water and squishing. Thanks for the information, I have to go through the rest of the website. Regards.

You are VERY lucky the little orange devils just showed up! they are a southern species that do not overwinter in northern areas. They blow up on the wind in the summer and always reach my location in Missouri by the summertime! Soap and water, water spray or squishing are the organic way to go, but there are many non-organic ways if monarchs are not present…if you are so inclined. Just because you have them now does not mean they will return without the right combination of weather conditions. According to one researcher, the Aphis nerii, Oleander aphids, change the chemistry of the plant in a way favorable to monarch caterpillars, so no worry there. If you are collecting seeds, I think the various seed bugs are more harmful than the aphids…but not sure. I consider you lucky as I know I will have these orange devils next year…without a doubt!

Great article except that there are insecticides that do not harm aphids and will harm monarch caterpillars . So seeing aphids on a milkweed plant does not mean the plant is safe for monarch caterpillars to eat .

Can you list some common garden insecticides that kill Monarch butterflies, but not aphids? That would be very helpful. Thanks!

Won’t the windex hurt the eggs and the catapillers

Are there any over the counter sprays that can be used on black flies. The leaves are turning yellow and falling off our milkweed

I have a somewhat remedy I have for you all. I grow milkweed to raise monarch butterflies and I have been getting a lot of spider mites lately. So I was talking to a rose keeper and they use small shop vacs with a small amount of water and soap in the bottom of the container they suck them off when they hit inside of the container of the Shop-Vac they died because of the soap water. give it a try maybe between that and other things from above you might solve the issue I hope this works for you all take care. Thank you all for your help doing your part for the monarchs….🐛🐛🐛

I have sent questions from my i- phone to you on your website and cant find any response! i have subscribed from my i-phone and my lap top! Help!!

Spray a weak solution of lemon detergent and water directly on the little buggers. The acid in the lemon dries them up quickly. Use it sparingly so whatever eggs and cats might be around don’t get hit by it. I’ve not found any dead caterpillars since I started using this mixture.

One of my milkweed plants looks all but dead!! It has 1 caterpullar on it and LOTS OF THE YELLOW APHIDS AND MILKWEED BUGS. Loiks like the aphids wete crawling all over my caterpillar!! Will this kill the cat? I will be picking them off with tape as suggested!!

I have tiny pale green bugs that look like eggs but when you touch them they crawl away can you tell me what they are I am very. new at this and thought at first they were monarch eggs

Those are aphids. They come in different colors!

I have tried EVERYTHING on our tropical milkweeds to control oleander aphids. Most of the plants have been destroyed. After spending hours of squishing and rinsing with water, they come back with a vengence OVERNIGHT!! Taken advise from local nurseries. One even suggested to leave the aphids alone….really? We do see beneficial insects, but not enough to keep these little vampires in check. Happy to offer monarchs nectar plants, but done with milkweed for now!!!

ms rita i know what your going through with the milkweed have the same problem sprayed em with mixture of cinn oil lemon oil and geranium oil still did not work im gonna dig it up attracting no beneficial insects including butterflies

I’m new at raising Monarchs. One of the first articles re raising Monarchs mentioned NEEM OIL to get rid of aphids. I used on my milkweed plants. NEEM made the leaves looked great. It also killed aphids and 14 caterpillars.

Eventually found two outstanding sources to mentor with: Tony Gomez at monarchbutterflygarden.net and Monika Mackle at texasbutterfly ranch.com.

Ants eat the honeydew liquid so they farm the aphids. Get rid of ants by putting ant traps at the base of the milkweed. No more ants, no more aphids.

I don’t recommend getting rid of the ants. They have their own role in the ecosystem — MM

For established infestations ant traps are one good attack. As long as the traps don’t attract other beneficial bugs. Even ants are beneficial.

Vigorously washing the honeydew, produced by the aphids, off the milkweed plant disrupts the ant’s genetic imperative to herd the aphids. Wash off most of the aphids at the same time. Eventually they won’t come back to an unproductive environment. If washing is started early in the season there will be fewer aphids and ants day by day until they abandon the plants.

Saving the world one bug at a time.

For indoor gardening I have had much success using sticky yellow-coloured paper hung above the plants or stuck into the soil which attract the adult aphids which then get stuck on the sticky paper and can’t reach new plants. Obviously, more useful when aphids are winged though I expect if the tapes are close enough to the plant leaves the non-winged ones may find their way over. It could perhaps work out of doors at least by limiting the spread to nearby plants. Also it helps to control the ant populations around your plants as they will happily cultivate and transport aphids from plant to plant.

I just started growing milkweed last year to attract butterflies. I now have huge amount of leaves being eaten. I am not into squishing them or using tape. Is there anything I can spray that will kill the bug but will still be able to attract butterflies?

The monarch caterpillars eat the leaves as they are growing, if you don’t see any pests but do see monarch caterpillars then it’s a success. the leaves will grow back, not to worry.

Good article. Note that your photo of the “all female” aphids includes an aphid mummy, which is a dead, parasitized aphid. This is GOOD, indicating that there are little wasps parasitizing and helping to control the aphids. You need some aphids to maintain the natural enemy populations so that you don’t need to resort to noxious chemicals.

Some large commercial monarch breeders use expensive pymetrozine http://www.greencastonline.com/imagehandler.ashx?ImID=7704535d-add7-409d-ba58-48d5b4576373&fTy=0&et=8 to kill aphids without harm to monarch caterpillars. Smaller breeders remove the caterpillars then spray less expensive Malathion or Sevin then rinse the plants off after 15 minutes, then put the caterpillars back on the plants.

Scotch tape is very effective at removing aphids. You can get right in all the tiny spaces without hurting the plant.

Thank you for all the info. I am new to milkweed plants, trying hard to encourage monarchs. They grew on my parsley for years but i think the birds were eating them. Obviously not happy. Is there any way to protect larvae from the birds before they are ready to go?

I tried using shiny objects as a deterrent. I look forward to reading this blog as I am an avid small gardener.

The caterpillars that like parsley are not actually monarchs, but rather black swallowtails. The caterpillars look almost identical, except for a couple of details, e.g. monarch caterpillars don’t have dots, and eat milkweed exclusively, not parsley. The adults look totally different.

I also have spider mites on my clematis. Each spring the plant blooms profusely for about a month then I notice no new blooms . I tried neem oil which seemed to work but it smells awful and I’m sure I am killing other “good bugs” Any ideas? The plants are approx. 11 years old; never moved. Was thinking of taking plants out in the fall and plant new. Don’t want to though. Thanks

Thank you for all the suggestions. I’ve given up on the aphids…just too many to try and get rid of. They have not migrated to other plants and hope they don’t. I did try alcohol and q-tip…it sure killed the aphids but I couldn’t keep up. Next year I will be more diligent. I also like the tape idea. I did try early on the insecticidal soap that was supposed to be safe. I did have caterpillars and tried not to hit them but they disappeared so don’t know if they died or not. So… I believe I need to get an earlier start and to be more diligent. As I said, I’ve given up now so will see what happens to my milkweeds. I hope I still have my pods but when aphids are on the pods, I don’t know if they will survive. Anyone know? I also have the milkweed bugs that LOVE the PODS. I mat be buying more milkweeds instead of planting the seeds for the existing plants. Hmmmm. A learning process for sure

[…] Texas Butterfly Ranch […]

I use an old plastic cup with lid (like a soda fountain cup) half filled with water and use Qtips to wipe them into the cup and let them drown. Next day dump the water and start over again. I tried all other methods and this is the most effective and cost effective without harming the caterpillars. I am wondering if the caterpillars eat the aphids. Good luck everyone.

I have used neem oil 3x on my milkweed plants as I wait to plant them outside. Are they forever deadly to the monarch caterpillars now? So sad…. they were grown organically and maybe I ruined them.

Amy, from what I’ve read Neem oil does not get absorbed into the plant.

I don’t think I can have milkweed in my garden, I believe I am the only one in my community that has milkweed that is why they are attracted to my garden. I have been battling these horrible aphids for years and they always win. I have diversified my milkweed plants but there are aphids on all of them now. I have hosed them off with a strong stream of water, every day for a week and they come back the next day, I cannot keep up. I even tried the soapy spray one year but it didn’t work well enough. The aphids end up killing the milkweed every time. I think I just need to replace them with something else.

Thanks for this — I have a bunch of aphids on my first potted swamp milkweed in a Houston suburb. They seem to be taking a toll.

If I may ask, I have another pest that has set up a bunch of tent-caterpillar-like small webs on the main branches. Any idea on what they are? I’ve been looking on the internet, and haven’t found anything yet. Thanks!

Ultimately nothing seems to prevent aphids on milkweed. Swamp seems to get less activity but Common is highly infested.

My experiments seem to have come down to a 1-qt mix of water with 1-2 parts blue dawn and isopropyl alcohol sprayed lightly directly on colonies of aphids with very light spritzes so as to prevent broadcasting the spray. After an hour, less in really warm times, sprinkle the plants lightly with a hose to wash off soap residuals. This prevents the soap residue burning the plants in the sun. I do this daily and the aphids seem under control. Small colonies is any. Skip a day or two and its as if I’ve done nothing to prevent them. Done right the plants actually can grow back faster than the aphids can suck nutrients from the plants.

Relocate any live cat’s to one bush and don’t spray that plant that day. Rotate around.

Good luck.

Not my best idea.

I agree that it is worth it to pay for professional services. They do a great job and are highly professional.

I am very interested in someone completing a comprehensive study of ALL monarch predators that are killing them in any stages of their development. Too many people are unaware that some “natural solutions” are actually harmful to the Monarchs. Using tachinids to combat the Japanese beatle is one example.

Your blog page is too unstable to write on.

I’d love to comment about my success with your taping aphid removal idea but can’t, the page is jumping.

After four years of seeking a solution to oleander aphids on milkweed I think I’ve come to a technique thanks to the Texas Butterfly Ranch forum. Not clean but close to absolute. And 100% natural.

All of this is predicated on catching the aphid colonies early on they feed and colonize on the newest growth.

Clear scotch tape wrapped sticky side out wrapped around a couple of fingers allows removal of most in early colonies. The tape attack seems to disorient them. The colonies only feebly reform after many are removed. They are then removable by a hard water stream.

I wear rubber gloves and wrap the tape around forefinger and index. I use my thump to lightly press the bugs on the top new growth against the tape. Not enough pressure to damage the plant. The colonies form on the newest growth. The hardest part is the small new leaves the bugs nestle into. Remember the aphids are holding on only by their proboscis and are easily disturbed.

After removing as many aphids as I can stand messing with I take a hard stream of water and, with a hand behind the bud for support, spray as hard as I can to dislodge the bugs. Spray up and under the buds. Some splashing involved. As others have pointed out the aphids have no genetic frame of reference in their lives to find and climb back up the plant so they are lost.

Come back to it a couple days later and do it again. The colonies will be smaller. I have more than a dozen plants. After a couple of weeks I could count the bugs on one hand. In five days of no followup I have two small colonies to attack. I think the theory here is to reduce the population enough that the aphids don’t feel the compulsion to sprout wings.

My milkweed plants are healthier than I have seen them in five years of growing. And strong. Start early in the season and this will not be a big issue for you. Also, the ants are gone having nothing to do on the plants.

If you already have eggs and larva on the plant try hard to protect them before using the water hose. I remove some larva and move them indoors for safe captive growing and later release once the adults emerge. I have strong healthy blossoming milkweed just waiting for the migration to get to here SE Pennsylvania.

Best of luck folks. And thanks a ton to the Texas Butterfly Ranch for this forum.

This was informative, but very difficult to read because the page kept jumping around.

What is up with this jumpy page? So frustrating!

This page jumps as other people have mentioned and makes it impossible to read what I’m sure is excellent information. Hope you can fix it.

Thank you. Will look into it.

I’ve been exploring various ideas for battling against Aphis nerii on my milkweed gardens for about two years now. Squishing them with my fingers works, of course, but everyone knows how nasty that is (unless you wear latex gloves for the assault). I liked the idea I read somewhere of buying a tiny, cheap vacuum cleaner designed for cleaning computer keyboards but found in practice that the one I bought doesn’t have quite enough sucking-power to efficiently remove the little yellow vampires. Tried using a small, stiff-bristle brush and that seemed promising…then I had a revelation that I’ve not seen anywhere: Maybe I’ve invented a new use for that modern miracle, the electric toothbrush!

Bought a cheap ($12) high-speed cordless toothbrush via Amazon (37,000 vibrations per minute…woof, it sounds a little bit like a dentist’s drill) and took it out to the milkweed beds this afternoon—wow! Running that little vibrating brush over an aphid-colonized stem effortlessly knocks them into the soil in droves. It took about 5-6 minutes to substantially clean the aphids out of a 3’ x 5’ milkweed bed containing six mature A. curassavica plants and ~20-25 caterpillars. In fact, since only very light contact with the rapidly vibrating brush-head was sufficient to dislodge the aphids it was easy to work around the caterpillars and delicately reach into occluded areas on the plants. I can’t say I removed every aphid but the few remaining ones looked distinctly sad and lonely. Like they’ve seen the devastation of their buddies and have an inkling that they are next….

I don’t know whether the displaced aphids can readily find their way back onto the plants but I will watch their progress with great interest, electric toothbrush in hand and a malicious smile on my face…😄

Thus far I have not lost a single milkweed flower this year. I keep a dozen plants to feed larva as I raise them.

As you note Monika “Small populations of aphids are pretty harmless to the plants, but when you get a large colony, the milkweed suffers.”

This is the behavior that allows control of the oleander aphids population. My goal is not eradication but control the population, prevent overpopulation. It is the over-populated colony that incites the growth of winged females that then fly to clean plants.

The trick I am attempting this year is water. Pressurized water. It knocks them off the plant preventing overcrowding. The home stores have a 1-gal. pump pressure sprayer you can set on stream. I started early in the season when I first spotted the yellow monsters. I will squish them but this is better. Cradle a nascent flower in your hand and spray using a sharp stream. Also spray from below the flower to drive the aphids from the inside of the buds. If need be cut off large infestations.

Dedicate time to a daily effort until the population gives up.

Preventing overpopulation with water spray prevents the buildup of honeydew. I believe this prevents the attraction of ants that symbiotically help the aphid colonies to grow. Three weeks in and there are a few lost looking aphids hiding in the flowers of one plant. easily removed. Few ants.

[…] + Read More […]

I’ve had milkweed and monarchs for 6 years and always wind up with heavy aphids. This year for the first time I recently removed all the seed pods just to improve the grungy look of the late summer plants. Just noticing this AM, ALL the aphids are gone. Removed seeds @ 2 weeks ago. Is that connected?

Robert;

Interesting. I pick seed pod to keep the plants flowering.

I had the following experience this year.

Thus far I have not lost a single milkweed flower this year that I didn’t plan to lose. I keep a dozen plants to feed Monarch larva as I raise them.

Small populations of aphids are pretty harmless to the plants, but when you get a large colony, the milkweed suffers.

From the moment the aphid is in the world they are reproducing with only females in the colony. When they get crowded some few will grow wings and go looking for fresh milk weed.

Preventing the aphid colony from growing to critical mass and spreading is the garden management that allows some control of the oleander aphids population. My goal is not eradication but control the population, prevent overpopulation.

The trick I attempted this year is water. Pressurized water. It knocks them loose from the tender new plant growth and preventing overcrowding. The Home depot has a 1-gal. pump pressure sprayer you can set on stream. I started early in the season when I first spotted the yellow monsters.

The aphids are softer than the new plant growth so it’s easy to crush them between gloved fingers without damaging the plant. I will squish them on the top, new growth and buds. But spraying is better. Cradle a nascent flower in your hand and spray into it using a sharp stream. Also spray up from below the flower to drive the aphids from the inside of the buds. If need be cut off large infestations disposing of them in a water bucket with dish detergent.

The water also washes from the plant the honeydew that ants love. There is a symbiotic relationship between aphid and ant. The ant protects the colony from predators and herds and aphids to new growth. The aphid secretes honeydew that the ants take back to their colony. Wash the honeydew off the plant daily and the ants won’t thrive. This makes the aphids lost and prey to other predators.

Dedicate time to a daily effort until the aphid population gives up.

I still have some of my original flower clusters on the plants in mid-August. And no aphids at all.

In July I allowed the aphids to grow for a week to tempt fate. Colonies grew like mad. I removed as many as I could with squishing and water, only some flowers were cut from the plants as hopeless. I got them back under control in days and the colonies faded. I am now aphid free for weeks. I still have plenty of flowers.

I also noticed that the aphids do not seem to aggressively migrate to more plants as long and they don’t achieved that critical mass of over population. Look out for aphids crawling up the cane after being washed off

Also, planting marigold and wild onion around the base of the milk weed repels the ants, some.

My milkweed was covered with aphids. I learned that ants “farm” the aphids to get the sweet secretions they produce. I put out ants traps and the aphids disappeared.

Honeydew symbiosis. (Nothing new just another synthesis.)

Without honeydew there are no ants. Without ants there are no organized aphid colonies.

Find young aphid colonies and wash the honeydew off, along with most aphids. Snip off only heavily infested buds. Spray the aphids off the buds with a water pump garden sprayer. While reducing the aphid population the core purpose of spraying is to wash off and keep the aphid honeydew from accumulating on the plant and attracting the ants. Wash it off. The ants are no longer attracted to a plant without honeydew. This keeps the aphids from growing the colony to its critical size needed for it to produce females for expansion to more plants . Simply disrupt this honeydew symbiosis.

Reducing the honeydew and aphid colony from the start, by mid June last year I had no more aphids. More important, to me, I had not lost one bud on more than a dozen plants.

Have a great summer.

I see this Q&A is slightly dormant but I hope to get an answer. A bit of back info:

A few weeks ago I spotted 2 monarch chrysalises hanging on a potted pencil cactus next to a mostly neglected milkweed plant in a pot I chopped down last fall. Those 2 green chrysalises caused me to spend most of the afternoon building them a house out of a tall cardboard box complete with netting over windows and garden mesh attached to the inside of the top cover which is where I attached those 2 green jewels. Then I noticed several caterpillars on the old milkweed plant so I put them in a small plastic tub with milkweed leaves. I ordered a mesh butterfly habitat with arrived in 2 days. I kept finding a few more cats and I read all I could find to take care of them. I was soon to run out of milkweed so I went to a nursery and bought 2 small milkweed plants. I planted them, found cats there and used most of those plants to feed 13 little guys of various sizes. The next morning the milkweed had been mowed down by bunnies. I quickly scrambled to 4 other plant nurseries, no one had milkweed until the last place so I bought 3 plants. The nursery staff couldn’t tell me what kind of milkweed these were.

I had 13 fat cats and I started feeding them from the new plants. Some cats went to the top of the new habitat, started to form the “J” and their heads turned green but then they died. Seems like 2 at a time my caterpillars were oozing out green stuff and died. I suspect the first 2 plants or the second batch of 3 milkweed plants had been sprayed. Maybe both sets of plants?- I really can’t tell. I lost all 13 that I raised but I was THRILLED when the first 2 chrysalises that survived in nature actually morphed into beautiful monarchs. I kept them in my homemade habitat until the 2nd day, I offered them a sunny spot with some flowers and sugar water and set them free that afternoon. SO COOL. In the meantime I found 2 eggs and several more cats in various stages on the new plants, but I didn’t want to continue feeding them leaves from the new plants. Luckily I had just enough new leafs to offer my 11 critters and I only gave the largest cats leafs from the new plants. I just wasn’t sure if those plants were safe and I didn’t want the tiniest cats eating those. The same situation happened. A few “J’d” then died, a few oozed green and were gone, but 2 more made it thru the process! So out of 26 I had 4 monarch butterflies, I think 1 female and 3 males.

SO!

Here’s my question: Assuming the 5 milkweed plants I bought were all sprayed, if I just let them grow until next spring, (inside a pool screen, no butterflies will lay eggs on them) will the chemicals be worn off and the plants be safe by then?

THANK YOU!