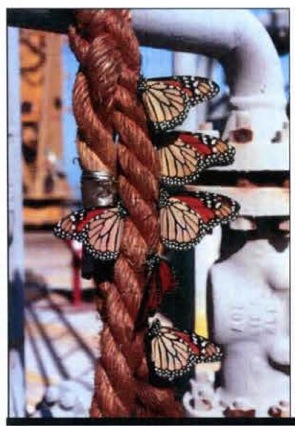

Monarch butterflies resting on an oil rig rope in the Gulf of Mexico in Oct.-Dec. 1993. Photo courtesy Dr. Gary Noel Ross

“The experience on the rig was certainly an unforgettable one…to see the cloud coming from all around in a mass that settled on every available space from the top of the derrick to the floors. Everything was covered…. There were butterflies on top of butterflies. The deck hands were busy with wash-down hoses and had to keep it up to be able to handle the gear while drilling. Some of the older hands said it was a yearly occurrence in the area.”

–Mrs. Hylma Gordon of Hattiesburg, Mississippi, as told to Bryant Mather and published in News of the Lepidopterists’ Society (July/August 1990), No. 4, page 59:

Dr. Tracy Villareal is atypical in the butterfly world. He’s a PhD–but not in entomology. He’s a butterfly breeder–but as a marine biologist at the University of Texas at Austin, he spends his days looking at small marine plants called phytoplankton

rather than coaxing caterpillars to morph to the next stage. Dr. Villareal and his partner Dr. Barbara Dorf, who serves as a Fishery Biologist at

Texas Parks and Wildlife Dept. along the Gulf, operate the Big Tree Butterflies farm in Rockport, Texas, when they’re not pulling duty at their full-time jobs.

So it seems the perfect marriage of passion and profession for Villareal to develop an app to track Monarch butterflies crossing the ocean–that is, the Gulf of Mexico. “As an oceanographer I can’t bring much to bear in the terrestrial world, but this is flying over water,” he said in a series of conversations discussing his latest project.

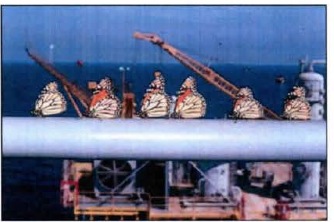

As if migrating 3,000 miles were not impressive enough, evidence suggests that Monarch butterflies, like the ruby-throated hummingbird, cross the vast 450+ mile expanse of the Gulf of Mexico each year to make their famous trek to Michoacán in the mountains of Mexico. Another scientist, Baton Rouge-based Gary Noel Ross, who holds a PhD in entomology, documented the existence of myriad Monarch roosts on oil rigs as late as 1993.

Dr. Villareal heard about the ocean crossings via the DPLX list, a listserv for butterfly enthusiasts, and began researching the idea of verifying whether or not the phenom continues today.

Given the lack of population on oil rigs, Dr. Villareal figured the best way to collect data would be to develop a very simple app that oil rig workers, fisher persons, even helicopter pilots might use to collect data on the whereabouts of Monarch butterflies. The app would register and automatically geolocate the datapoint, which would load to the cloud and populate a map, providing a real-time picture of where Monarchs are congregating at sea. The app would work in a similar fashion to the well-utilized Journey North app, but it could go global and would be cloud-, rather than server-based.

“This needs to be as simple as possible,” said Dr. Villareal by phone. “I don’t want (oil company) management out there telling people this is too distracting.”

But will oil rig workers take the time to contribute citizen science data? It wouldn’t be the first time.

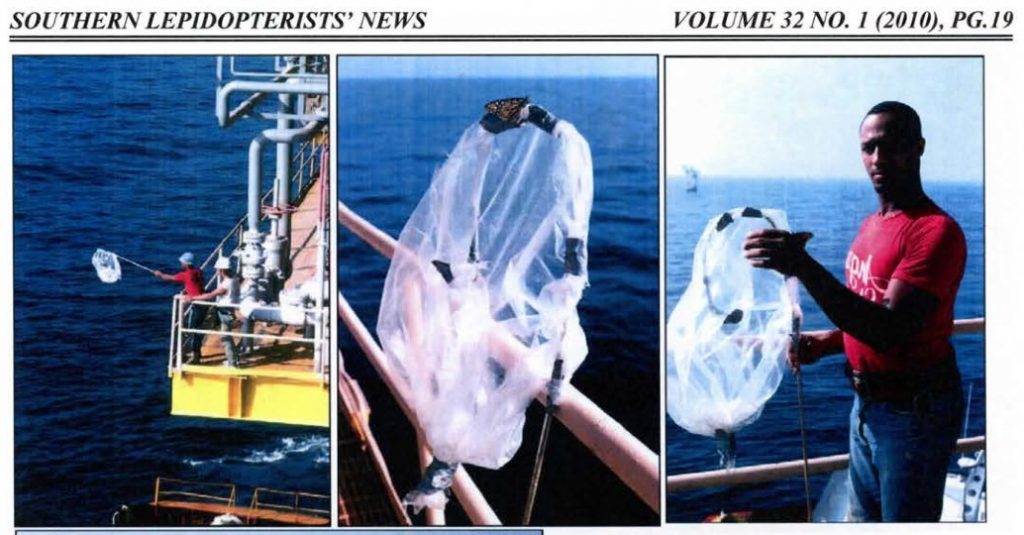

Photos published in the Southern Lepidopterist Society newsletter by Dr. Ross, taken in the 90s, show oil rig workers netting butterflies. See below.

Oil rig workers netting and tagging Monarch butterflies in October 1991. Photo via Southern Lepidopterist Society Newsletter

Dr. Ross supports the introduction of technology to the phenomenon he labeled the “Trans Gulf Express.”

“Technology has a lot to offer for field biologists,” said Dr. Ross via email, adding that if Dr. Villareal’s project gets underway and the app widely embraced, good data will be harvested that can be easily analyzed using digital tools. “At the time of my work I had to rely on helicopter pilots and rig workers calling in to me at my location,” he recalled. Dr. Ross offered that he personally thinks that Monarchs continue to cross the Gulf.

Dr. Chip Taylor, founder of Monarch Watch, the University of Kansas-based citizen scientist program that tags Monarch butterflies, agrees.

“As long as there are Monarchs, they will appear from time to time on rigs in the Gulf,” said Dr. Taylor. Dr. Taylor and Monarch Watch are partners in the venture, kicking off a fundraising effort to raise $8,000 for Villareal’s app with a $4,000 matching grant–half the total. The funds will be used to take the app beyond the development phase. “It may help us learn more about the how and why,” said Dr. Taylor. “The survival question will be more difficult to answer,” he said.

Dr. Tracy Villareal’s app will track Monarch butterflies on oil rigs. Click on over and help raise the needed funds to take the app out of the beta stage.

Want to help? Check out the fundraising campaign, Tracking Monarch Butterflies on Offshore Oil Platforms, which launched today on Hornraiser, a University of Texas- sponsored crowd funding platform.

Related posts:

- How to Track the Monarch Butterfly Migration from your Desk

- Google Earth Tour: Monarch Butterfly Migration

- Texas Parks and Wildlife Launches Milkweed Monitoring Project

- Pollinator PowWow Draws 100s from Texas and Beyong

- Mega-Grower Colorspot to Consider Growing Chemical Free Milkweed

- Q&A with Dr. Lincoln Brower

- Survey: Monarch Butterfly Enthusiasts will Pay More for Clean, Native Milkweeds

- MIlkweed Guide for Central and South Texas

- Endangered Species Act Wrong Tool for the Job of Monarch Butterfly Conservation?

- How to Get Native Milkweed Seeds to Germinate

- Monsanto: Absolutely committed to Monarch Butterfly Conservation

- How to Raise Monarch Butterflies at Home, Part One

Like what you’re reading? Follow butterfly and native plant news at the Texas Butterfly Ranch. Sign up for email delivery, like us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter, @monikam.

We already know very few fall migrant monarchs “cross the vast 450+ mile expanse of the Gulf of Mexico each year to make their famous trek to Michoacán in the mountains of Mexico.” How? Two tagging studies. 1) Professor Richard Rubino supervised the tagging of 12,500 monarchs in the 1990’s and early 2000’s in the Florida panhandle area and he found:

http://www.learner.org/jnorth/tm/monarch/TagRecoveryFL.html

“of the nearly 12,500 monarchs he has tagged at St. Marks Refuge in ten years, only three have been found in Mexico. This is far, far below the ratios recorded elsewhere. According to Dr. Chip Taylor of Monarch Watch, nearly 1% of all monarchs tagged are found at the sanctuaries in Mexico.”

So that means western Florida gulf coast fall migrants are about 40 times less likely to make it to the traditional

overwintering sites in central Mexico (state of

Michoacan) as compared to fall migrants tagged in the northern USA.

2) None of the hundreds of fall migrants Harlen & Altus Aschen have tagged along the coast of Texas over the past 15 years have been recovered at the overwintering sites in central Mexico. However, some fall migrants do make it across the Gulf of Mexico and they do not necessary end up in Michoacan. Some have been video recorded on the norther tip of the Yucatan peninsula about https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MvIw4EBeccs

Hi Paul,

What you say is true, but is not relevant to this study. There are very few rigs on the Florida continental shelf. Most of the structures are south-ish of LA. The corridor that Dr. Ross speculated on is from SW-central Louisiana into the heart of the oil rig deployment. The mass swarming he mentions from historical records was at rig 150 miles south of Cameron, LA.

I’m not sure what to make of the tagging data from along the Texas coast either. They’d already be ashore or have a direct land route. Again, interesting information but not relevant to the study. I think it is important to note the fundraising is to build a tool that will have multiple uses. The Gulf of Mexico is a good place to test it out. We don’t know if this offshore phenomenon even occurs any more. Dr. Ross’ observations were nearly 20 years ago. So, I don’t think it is safe to assume that the conditions are the same.

I agree with Dr. Viillareal. And I think absence data is extremely important. In addition, the focus on the final destination being the MBBR may not be correct. Do monarchs try to cross the Gulf and end up in the Yucatan, Cuba, etc? There is already some evidence to suggest that. But getting confirmation of the pathway is key. There are so many questions to be explored–Do monarchs try to cross deliberately, or just get blown out to sea? How does weather effect them? Where are they headed? Do they make it, and in what numbers? How do they do it? Getting observers involved on both sides of the Gulf will be wonderful, and this app can go international. The biggest mistake we could ever make is ASSUMING we already know the answers. That would be the death of real scientific investigation.

wonderful idea as long as they don’t get caught up in spilled oil? It is a “rest area” from the long journey. Maybe they could feed on juicy juice on a sponge in a bowl while they are there? We must do everything we can to save them. It is a Natural Wonder that we must preserve, Please!