A new study released last week found that the monarch butterfly’s breeding population is stable and thriving, while its fall migratory population is in serious decline.

Migration studies expert Andy Davis, assistant research scientist at the University of Georgia Odum School of Ecology, served as lead author on the research.

Titled “Dramatic recent declines in the size of monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus) roosts during fall migration,” the study states that the fall migration of monarch butterflies is “under imminent threat, even if the species’ overall survival is not.”

Davis tapped into a dataset gathered by Journey North, a conservation organization that tracks the migration of monarch butterflies and other creatures with the help of community science volunteers.

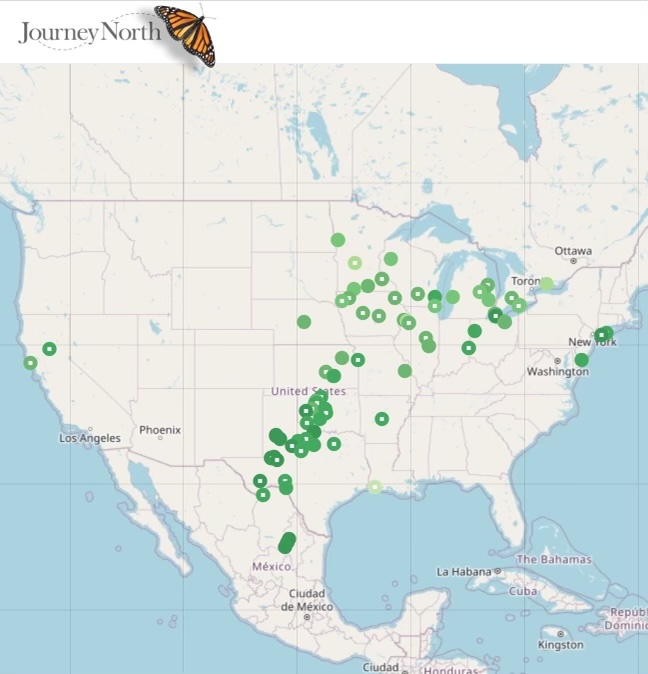

Journey North invites community members to submit data that tracks the roosts of monarch butterflies each year. Here, roosts reported through October 19, 2024. –Graphic via Journey North

Since 2006, Journey North has encouraged volunteers to submit observations including the date, time, place and size of migrating monarch butterflies’ fall roosts. Davis and his team examined 2,600 records collected and reported by the Journey North community over the last 17 years and determined that along the migratory flyway, “roost sizes were generally declining, with a median of 6.6% decline per year.” The study also noted that roost size declined more dramatically along the more southern edges of the migration.

“By our calculations, the size of migratory roosts in Texas today are 80% smaller than they were just 17 years ago. The losses have been stark and rapid,” Davis noted on Facebook, when announcing the study on his Thoughtful Monarch group page.

Courtship flight. Monarchs are increasingly breaking their diapause, not migrating, and reproducing locally in the fall. –File photo

“While we’re excited to have this finally published, it unfortunately is a sad story,” Davis said when sharing the University of Georgia press release.

“Our findings indicate the monarchs simply are failing to even reach Mexico in greater and greater numbers each year. We don’t know if they are dying en route, or if they are simply dropping out along the way. Either way, it means that the winter colony sizes will continue to be small, regardless of how many milkweeds are planted in the U.S. or Canada,” Davis said.

“How do you say that the monarch butterfly is going extinct in the winter while they’re perfectly healthy in the summer?” asked the study’s co-author William Snyder, a professor of entomology in UGA’s College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences. “This paper fills in that gap by saying the problem is that fall migration.”

Davis added: “Either they’re losing their ability to migrate or they’re losing their will to migrate.”

I would suggest it’s the latter. As I explain in my book, The Monarch Butterfly Migration Its Rise and Fall, which cites Davis and other scientists extensively, migrations are HARD. For monarchs, they are often fatal. Creatures migrate because they have to, in a quest for reproduction of the species, which is the biological definition of success. NOTE: In the fall, monarchs either migrate or reproduce; they do not have the capacity to reproduce. Those that migrate, reproduce in the spring.

Every scientist I spoke with in my research—Founder of Monarch Joint Venture Karen Oberhauser, Monarch Watch founder Chip Taylor, Washington State University’s David James, and others—agreed that the monarch butterfly migration is going away. These experts tell us that migrations are ephemeral, serving a moment in time. When that time passes, creatures adapt.

If monarchs can reproduce locally in a hospitable environment that provides nectar, shelter, mates, and host plant, why take on the arduous, often deadly journey of migrating to Mexico? It seems likely they are “losing their will” to migrate, as Davis suggests.

While climate change is definitely contributing to monarch migration decline, Davis considers the main drivers of a growing nonmigratory population to be human meddling. An infographic he posted on his Facebook page states “Human actions–captive rearing, planting non native milkweeds and the rise of the OE parasite are likely causes” of reducing the fall migration “to a trickle”

Read the study here.

TOP PHOTO: Lonely monarch butterfly on the Llano River in the Texas Hill Country during peak monarch migration, October 2024.–Photo by Monika Maeckle

Related articles

- “Weird” weather has scientists concerned about this year’s monarch butterfly migration

- “Snoutbreak” in Central and South Texas: American Snout butterflies inundate Hill Country

- Declining monarch butterflies: Mexico population drops 59%, West coast population down 30%

- US Fish and Wildlife Service rules monarch butterflies worthy of protection, but doesn’t have resources to provide it

- Recent IUCN “endangered” listing creates confusion for monarch butterfly fans

- IUCN revises listing of monarch butterfly from “endangered” to “vulnerable”

- AS ESA listing looms, new study challenges dogmatic narrative that monarchs are in decline,

- Endangered Species Act: wrong tool for monarch butterfly conservation?

- USFWS gets three more years to evaluate monarch butterfly ESA status

Interesting study. Not sure I would agree with the quoted Facebook post regarding captive breeding, etc. (last paragraph of the article). Global climate is changing and I have read that the migration patterns of other species (specifically birds) is also changing. One could make a case that if migration patterns are changing for other species, then climate change is the main driver, not simply a contributing factor.

It would be interesting to see a meta-study regarding the changing migrations and changing habitat areas of a variety of species.

I like the quote “migrations are ephemeral, serving a moment in time. When that time passes, creatures adapt.” So very true.

A rebuttal to Andy Davis’s migration mortality hypothesis can be found in this open access scientific journal article: J. Pleasants, W. E. Thogmartin, K. S. Oberhauser, O. R. Taylor, C. Stenoien, A comparison of summer, fall and winter estimates of monarch population size before and after milkweed eradication from crop fields in North America. Insect Conservation Diversity, 17, 51-64 (2024).

Excerpt from Conclusion: “Because summer surveys did not provide an accurate measure of the monarch population during the pre-eradication period, there is no need to advance the migration mortality hypothesis to explain the discrepancy between summer and winter estimates of population size. “

At heart, SUN SPOT variations drive “climate change”. “Human meddling” , over all, affects only the periphery ……

Based on my understanding of climate change, most scientists say the exact opposite is true.

Has anyone at all, considered what the impact of emanating cell towers has done to the internal radars of migrating birds, butterflies and other beasts? How about all the wind farms along the way, that actually “stir” the air and cause ripples in the pathway?

I had read an article about a week or two ago, that asked folks to turn out their porch lights, so as not to confuse migrating birds. The climate has changed forever on its own accord, but the “stuff” that is being zapped into the environment, no doubt would cause glitches in their sensitive senses! Just thinking outside the narrative box : )

[…] past week, she wrote on Instagram and her website: “A new study released last week found that the monarch butterfly’s breeding population is […]

It’s the chemicals mostly that is causing this decrease! The cdc’s fight the bite program which killed 160 of my various caterpillars leaving my plants toxic for my entire summer in sugar land Texas!! Also leaving me with morgellons! A threat to butterflies and humans!!

Climate change has been disputed by scientists, people have got to wake up!!