“Can well-meaning people sometimes make things worse?”

That was the provocative subhead on an article by Dr. Jeffrey Glassberg, founder and president of the North American Butterfly Association (NABA) in that organization’s most recent edition of American Butterflies Magazine.

Glassberg, who holds a PhD in biology, a law degree and credentials as an entrepreneur, author and butterfly advocate, challenged the recent scientific assertions made by Satterfield et al that Tropical milkweed, Asclepias curassavica, is bad news for Monarch butterflies.

Glassberg challenges the study’s claims about Tropical milkweed’s appropriateness in South Texas, where the North American Butterfly Center operates in Mission along the Texas-Mexico border.

In case you missed it, Dara Satterfield, a PhD candidate at the Odum School of Ecology at the University of Georgia, and her graduate advisor, Dr. Sonia Altizer, a disease ecologist at Georgia and one of the foremost experts on Ophryocystis elektroscirrha, a Monarch-centric spore driven disease known as OE, suggest in their research that sedentary winter-breeding butterflies are at increased risk of OE. They speculate that Tropical milkweed, Asclepias curassavica, the most widely available but technically nonnative milkweed and favorite host plant of the Monarch butterfly, may be damaging the Monarchs’ abilities to stay healthy, on track and make their way to Mexico.

Native to Central America and Mexico, Tropical milkweed grows well and sometimes year round in Texas and Florida. Scientists worry that it might be confusing Monarchs, making them skip their migration and reproduce locally. When they do that, spores from butterflies infected with OE build up on the plant and may transfer the disease to other caterpillars, chrysalises, and later, butterflies, resulting in crippling and even death. Read the Tropical milkweed fact sheet.

Just to be clear: Satterfield, et al DO NOT THINK TROPICAL MILKWEED IS EVIL. In fact, they say exactly that in a statement issued by Monarch Joint Venture and shared via the DPlex, a listserv that reaches about 800 butterfly followers.

“Tropical milkweed itself is not ‘bad.’ (It provides larval food for Monarchs in many places where it occurs naturally, such as across the Caribbean, Mexico, and Central America.),” the scientists said in a statement released in January following the milkweed kerfuffle.

“The truth is that we don’t really know,” if butterflies infected with OE at winter-breeding locations will impact the Monarch population as a whole, the statement said.

So to be fair, the scientists admit that much is still to be determined about the impact of Tropical milkweed on the Monarch butterfly population. That’s why they suggest cutting Tropical milkweed to the ground over the fall and winter–so the OE spores can’t build up.

Glassberg takes the Satterfield et al. study to task, challenging the assertions with his own data fueled theories.

Monarchs and other milkweed feeders host on the evergreen Pineneedle milkweed in Arizona and have lower than average OE infection rates. Courtesy photo via Ladybird Johnson Wildflower Center, Sally Wasowski

Nonmigrating Monarch butterflies in Hawaii and Arizona have lesser-than-average levels of OE infection, notes Glassberg, pointing out that some Monarchs overwinter and sustain themselves on evergreen milkweeds like Fringed twinevine and Pineneedle milkweed.

Such examples “suggest that the level of OE infection might not be as highly correlated with non-migratory behavior and that the presence of an evergreen supply of milkweeds doesn’t necessarily mean that OE levels will be high, as Satterfield et al. conclude,” he writes.

“Perhaps the higher levels of infection that Satterfield et al. found to be associated with Tropical milkweeds were due to temperature effects or other factors not intrinsic to Tropical milkweed,” Glassberg writes, suggesting that global warning and higher temperatures beg the question: what is a native plant, anyway?

Climate change is already making the range for Tropical milkweed creep north and “if and when that happens, wouldn’t it be a good thing for there to be extensive areas in the southern United States that might serve as reservoirs for Monarchs that would then be able to repopulate more northern areas, much as Painted Ladies and American Ladies do now?”

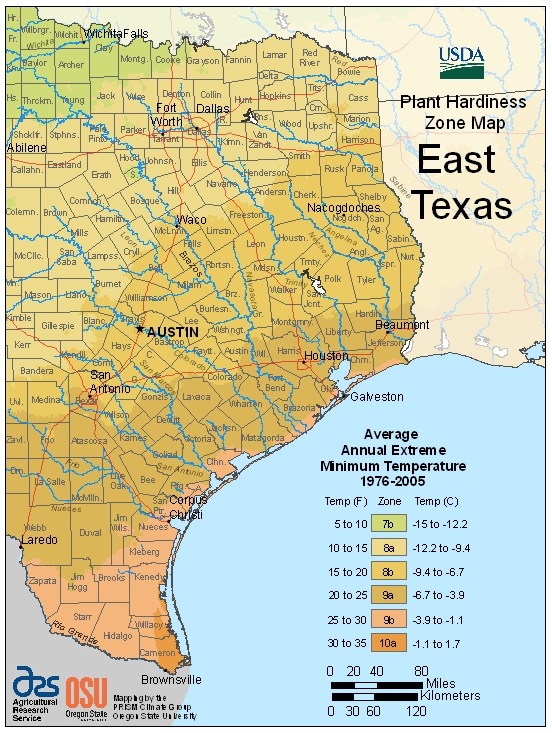

In 2012, the USDA redefined hardiness zones in response to climate change. San Antonio moved to Zone 9a from Zone 8b. Will Tropical milkweed eventually rank as “native”? Screengrab via USDA

When asked about the article, Satterfield responded by email that “We do plan to address why our paper rules out effects of temperature and geography and points to year-round milkweed as the source of the high levels of disease.”

Glassberg makes a lot of sense here. His characterization of Tropical milkweed as a “life buoy” for Monarchs until the commercial market for native milkweeds can be developed holds great appeal. In a recent webinar staged by US Fish and Wildlife Service on creating Monarch butterfly habitat in the U.S., experts stated that it will take a minimum of five years to create a commercial market for native milkweeds. That’s a long time for Monarchs to wait around for the perfect locavore food, especially when Tropical milkweed is already on the market, easy-to-grow and very affordable.

Tropical milkweed: “Life buoy” for Monarchs and other milkweed feeders until the native milkweeds are available. Photo by Monika Maeckle

My approach in the garden includes Tropical milkweed as a foundation, natives preferred, but more challenging to grow. And I’m not alone. Plenty of us who follow Monarchs believe the Tropical milkweed debate is bloated and misguided.

Here’s what Edith Smith, one of the most seasoned, experienced and thoughtful commercial butterfly breeders on the planet and owner of Shady Oak Butterfly Farm in Florida, thinks about the focus on Tropical milkweed: “…They’re so fussy about that plant. If only they’d stop to think, they’d realize that if a couple of treaties had been written a bit different and the southern border of our country had been drawn a hundred miles further south, Tropical milkweed WOULD be a U.S. native. SHEESH!”

She adds: “As far as it being good/bad for Monarchs … let’s remove all the Tropical milkweed from Mexico and see what happens to the Monarch population in the US. That in itself should answer the question.”

Another Monarch expert suggested everyone just chill on the Tropical milkweed fixation, pointing out that a better investment of time, energy and money would be replenishing the million-plus acres of pollinator habitat lost each year. Arguing about narrow strips of Tropical milkweed along the coastline constitutes a huge misplaced priority.

“Just cut the dang stuff down at the end of the season–maybe twice. We’re wasting too much time on this issue. There are bigger problems,” said the source.

Even Catalina Trail, the woman who discovered the Monarch butterfly roosting sites in Mexico back in 1975, plants Tropical milkweed in her Austin garden. “I would prefer to have native milkweeds in my yard, but they’re impossible to grow,” she said by phone. “I have two Tropical milkweeds in my yard.”

This website has reported repeatedly on this topic and I am at peace with my stance: Tropical milkweed fills a gap for Monarch butterflies. Just cut it back.

Both early and late in the season, Tropical milkweed is often the ONLY milkweed available for migrating Monarchs. The eggs of the caterpillars pictured above were laid in late March and because of our cool spring, no native milkweed was up and out of the ground yet. My Tropical milkweed from last year, which had been cut to the ground in December as per best practice, had plenty of fine, tender new leaves ready for the hungry critters when they arrived.

Had I not this Tropical milkweed in my yard, the migrating Monarch who laid the eggs that became today’s caterpillars in my yard would have had to keep flying, seeking milkweed that in this cool Texas spring was mostly absent until now. Who knows where/if she would have found a place to lay her eggs before perishing?

Meanwhile, in the Fall, the only native milkweed I see is Swamp milkweed along the Llano River, and it’s usually in bad shape, ravaged by aphids and the summer heat. Tropical milkweed is the only food available for late season caterpillars, and the lack of available caterpillar food often results in a caterpillar food emergency, with folks calling around town to friends and local nurseries to see if anyone has clean, chemical free milkweed available. Some breeders and enthusiasts have taken to offering pumpkin, cucumbers and other “alternative fuels” for late season Monarchs.

Making an issue about Tropical milkweed reminds me of the locavore food movement: idealistic, admirable, but now always practical. The caterpillars have to eat.

Imagine you’re driving cross-country with your family and you and the kids find yourselves famished. Sure, you’d prefer to stop at a local diner where good food was whipped up from scratch from local organic ingredients, responsibly harvested, lovingly prepared, delicious, nutritious and affordable.

But that’s not always possible. Sometimes you have to hit the drive-through of a fast-food joint because that’s all there is. And that will get you to the next place.

Related posts:

- Q&A: Dara Satterfield

- Tropical Milkweed: to Plant it or Not, it’s Not a Simple Question

- Q&A: Dr. Lincoln Brower on Milkweed, ESA, and Monarchs

- Endangered Species Act: Wrong Tool for the Job of Monarch Butterfly Conservation

- Milkweed Shortage Sparks “Alternative Fuels” for Monarch Butterfly Host Plant

- It Takes a Village to Feed Hungry Monarch Caterpillars

- Desperately Seeking Milkweed: Milkweed Shortage Creates Butterfly Emergency

- Pollinator Power on the San Antonio River Walk

- 2014 Monarch Butterfly Migration: Worst Year in History or Hopeful Rebound?

- How to Raise Monarch Butterflies at Home, Part One

- First Lady Michelle Obama Plants First Ever Pollinator Garden at the White House

Like what you’re reading? Follow butterfly and native plant news at the Texas Butterfly Ranch. Sign up for email delivery, like us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter, @monikam.

I am so glad someone has written to agree with me. I love the tropical milkweed. I have four raised beds full of tropical (4’x10′ each) in my Georgetown, TX back yard. I cut them back in Dec, they are regrowing now. I have been unable to grow other kinds of milkweed. Tropical is getting a bad rap.

The problem is not just with the spores on the plant alone, the tropical milkweed with its unique cardeneloide, voruscharin, seems to reduce spore load and keep OE infected Monarchs alive longer to ultimately spread the disease. Also, the other study indicating disrupting diapause for migration….

It is likely cutting them back often simply increases the toxic load of the plant as well. Tropical Milkweed /Asclepias curavassica also was demonstrated to reduce size of butterflies reared on it. So yeah, it is conclusive that Asclepias curavassica is not ideal for Monarch fitness. Find local ecotype native milkweeds.

Thanks, Monika, for another sensible article on this subject. Mike Quinn advised me to cut my tropical milkweed back twice a year to help prevent OE, so that’s what I do. Like so many others, I’ve tried and totally failed at growing the “native” milkweed. Of course, I’m totally open to anything that will help our Monarchs (including yanking out all the tropical) and have closely followed the debate about tropical. All I know is that in my little yard there are at least 25 thriving cats with zero signs of OE.

Thanks much Kathleen! The name of the nursery that is your source for giant milkweed, please?

My macaw and I are going on a road trip in March to SW Florida – the Everglades and other natural treasures. It would be easy for us to stop at that nursery on our way home. Thanks

During the past 10 days there have been multiple sighting reports on Journey North of brightly colored young monarchs in the central USA such as this one: https://www.learner.org/jnorth/sightings/query_result.html?record_id=1429566644 So that means these butterflies had to have grown up in the southern States or in Mexico on tropical milkweed and then migrated north, thus helping to repopulate the central States. Also means that a policy of cutting tropical milkweed down during the winter would reduce the production of new generation spring migrants that help repopulate the central States.

Hi Monika,

Nice posting. It’s unfortunate that tropical has managed to so distract us from the real problem of habitat loss. The solution of cutting it down is so simple, a suggestion based on inferred relationships in the Satterfield et al. paper. There seem to be two points in the paper. 1. OE infection rates are pretty high in monarchs collected from around the Gulf of Mexico. This overlaps with the range of tropical milkweed. That’s clear, although the infection rates are variable from site to site. 2. This correlation is used to infer that winter breeding created this high infection rate. That’s where it gets a little fuzzier. As Glassberg points out, their citation supporting winter breeding is not very robust. Okay, perhaps a better citation could have been found (like the unpublished Satterfield 2013 personal observation; should get that data out), but it still leaves the problem of did winter-breeding drive the high OE infection rate. An excellent test of this would have been to collect and eclose monarch caterpillars from the tropical milkweed. After all, that would leave no doubt as to their origin. An alternative hypothesis is that OE weakened monarchs preferentially abandon migration and collect around nectar sources. Migrating birds alter their behavior with the availability of resources, why not butterflies? There are many winter blooming plants in the nursery trade (my creeping purple lantana and rosemary bloomed all winter long in coastal Texas, much more so than the tropical milkweed every did). Many of them have their roots in tropical lands for the same reason tropical milkweed is so good. They keep blooming until a frost kills them. Sure, tropical milkweed would be a good place to look for monarchs, but is it what really created the high infection rates in non-migrating population? Can we exclude winter blooming landscaping in general as a refuge for OE weakened monarchs? Certainly, more work needs to be done on this question of what alters the fall migration behavior.

Regardless of this, I think the bottom line of cutting back tropical milkweed in the fall is prudent. It’s an excellent host plant in the spring and until the market can provide alternatives, there is little else most gardeners can do to aid monarchs. But remember that this is a DISTRACTION from the real problem of habitat loss. If we continue to lose a million acres a year of monarch habitat in the midwest (Chip Taylor’s estimate), then it will really not matter what we do with tropical milkweed.

Tropical milkweed does not contribute to habitat conservation, on the contrary. This is why organizations as the Xerces Society and the Monarch Joint Venture recommend only the use of native milkweeds, particularly milkweeds that are native to your region. Please, read my other comment and the links I provide.

You need to review Dr. De Roode’s study demonstrating infected caterpillars live longer as adult butterflies with OE infection. He also showed that the lifespans of OE infection free Monarchs was shorter when reared on Asclepias curavassica. So this explains the possible connection of why overwintering sites are so high in OE–harming uninfected Monarch fitness while prolonging lifespans of contagious Monarchs.

No cutting the plant back eliminates the highly toxic voruscharin found in no other North American species of milkweed so far. This extra toxic cardeneloide is also found in Gomphocarpus fruticosa and Calatropis procera, both of which are being distributed already in butterfly gardening circles in my area.

I would like to read the study on cutting back if you have a link or citation?

Tracy, in Arizona some fall migrants also stop migrating when they arrive in the lowland areas with trees and flower nectar (e.g. Rio Salado Park in Phoenix, AZ, http://3.bp.blogspot.com/-_NGu5dv7wkA/TV_RKwoNECI/AAAAAAAAAbw/AOKA4d5rhas/s1600/SAM_3242.JPG parks near the Colorado River in or near Lake Havasu City, AZ http://1.bp.blogspot.com/-Q302DsW5Knw/UuU2vRFeqdI/AAAAAAAABD0/UL8SvGDYnyg/s1600/MonarchBuckskinStatePark012014.jpg and OE sampling by the Southwest Monarch Study has determined those fall migrants have very low OE spore loads. So we already know that fall migrants that stop migrating long before they reach the main overwintering sites in central Mexico and along the California coast are not necessarily “OE weakened”. We also know the fall migrants that stop migrating and lay eggs on tropical milkweed in the Gulf coast states and northern Mexico in the fall produce offspring in late winter and early Spring, some of which migrate as evidenced by these recent reports on Journey North of young, brightly colored monarchs appearing in Virginia https://www.learner.org/jnorth/sightings/query_result.html?record_id=1430236899

https://www.learner.org/jnorth/sightings/query_result.html?record_id=1429566644

North Carolina: https://www.learner.org/jnorth/sightings/query_result.html?record_id=1429833712 Tennesee: https://www.learner.org/jnorth/sightings/query_result.html?record_id=1429666337 Therefore the policy of cutting tropical milkweed down to near the ground during the winter would reduce the production of new generation spring migrants that help repopulate the central States, especially if that policy was extended into the lowlands of northeastern Mexico. The policy would also force pregnant female fall migrants to lay eggs on the cut stems of tropical milkweed which in turn would cause most of the subsequent caterpillars to die of starvation.

Hi Paul,

Those are interesting observations, but much more data is needed before we can conclude that these single observations are representative of a general pattern. I would in no way advocate cutting tropical milkweed in northern Mexico. This is only for regions around the northern Gulf of Mexico. I can’t really address the comments about the populations in Arizona or California. Until a study with extensive sampling is conducted that is designed to test specific hypothesis about migrants and tropical milkweed in these areas, it is hard to know what point observations mean. Perhaps they are relevant to what happens along the northern Gulf of Mexico, perhaps not. At the moment, it is largely speculation unconstrained by data.

Most fall migrants have low OE spore loads (although that may mean different things to us), so that’s not a surprise. The question is whether some property of the habitat along the migration route in the east is accumulating contaminated butterflies in the areas that were examined. I think it is also important to remember that in biological systems, truth is rarely absolute or binary. We tend to want to make things black and white, but biology is messy and often has multiple factors in play at once and these factors change in importance with both time and space. It’s why the classical idea of how science progresses as defined by physics is a lousy model for ecology. There may well be both preferential trapping and winter-breeding going on.

I have been raising monarchs for about 10 years or more. I now have some plants that are two or more years old. I believe I have some cats with O.E. Is there anyway I can tell this by looking at the black cocoons and seeing some butterflies lying on the ground, kind of wriggling?

A few key points to keep in mind in the context of this article: 1) the Satterfield et al. paper focuses on a relatively small geographic range for these recommendations. The concerns with non-native tropical milkweed increasing the prevalence of OE are only in areas where the species can grow year round, allowing the parasite spores to build up on the plants. In areas where tropical milkweed dies back with a hard freeze, these disease concerns are no longer. 2) All species of milkweeds have the ability to spread OE if they have been visited by infected adults, who leave dormant spores behind for future caterpillars to eat. The issue arises when they do not die back naturally, as most native species do. 3) In all of this, the best recommendation put forth so far is to cut back tropical milkweeds in fall/winter (where they grow year round) to minimize disease spread. Researchers have documented that OE is occurring at a higher rate in the winter breeding populations in the southern U.S., and cutting back the tropical milkweed foliage during the winter could help to mitigate this issue. While it may seem relatively small compared to other issues that monarchs face, it is something that we can begin to address and alleviate yet another threat that monarchs are facing. They all add up, especially with a population that is small and vulnerable to begin with. We cannot simply forget about the “small” problems. Whenever possible, try to add/replace natives to your garden whenever they become available. 4) Lastly, this work is not complete. As with all scientific research, efforts to track this phenomenon will be ongoing and more will be learned and published in future years. Right now, researchers are going with their best recommendations for the information that is available. To expect that years of data be at our fingertips and all questions thought of an answered surrounding this issue is unfair to the scientific process. It is important to discuss these questions or methods that might help in future research, but do so in a way that is constructive. There might be limitations to that question, or perhaps just a need for more citizen science volunteers to gather more samples. Let’s be constructive, not critical!

We need to save entire habitats, not just an individual species. Organizations engaged on conservation of monarch butterflies as well as conservation in general list only native milkweeds. It is important to use not just native milkweeds, but those native to your area. The following organizations provide lists of milkweeds and information on local suppliers and regional distribution of milkweed varieties. None of them list tropical milkweed for very good reasons.

Xerces Society Milkweed Seed Finder (25 native species and list of regional suppliers), http://www.xerces.org/milkweed-seed-finder/

Monarch Watch Milkweed Market (15 native species and regional maps), http://monarchwatch.org/milkweed/market/

Monarch Joint Venture (about 20 native species by region), http://www.fs.fed.us/wildflowers/pollinators/Monarch_Butterfly/documents/MilkweedInfoSheet.pdf

Thank you Monika! I’ve been in email contact with Dara Satterfield as well. They did do some follow-up PR to try to correct the misconception of the appropriate use of Tropical milkweed. But the damage was done, and now we need to keep posting these updates and clarifications of the use of Tropical milkweed.

I’ll be posting this on my facebook page for our community to see.

What it boils down to is that if you want to preserve ecosystems, not just the flagship species, you have to plant local species of milkweeds. Follow the directives of the Xerces Society and the Monarch Joint Venture. They recommend only the use of native milkweeds, particularly milkweeds that are native to your region.

[…] curassavica, Tropical Milkweed) have been added, which continue to grow after summer ends. Recent discoveries indicate the presence of these milkweeds may actually stop migrating monarchs in their tracks, […]

I saw many monarch caterpillars on tropical milkweed at cran canaria, canary island spain last year.

Monarch butterflies are flying there throughout the year (!)

I must agree with the one monarch expert who stated to chill out and let’s focus more energy on saving precious land that’s being taken from our pollinators and wildlife.

Less focus on tropical milkweed. It would be wonderful if all the people who are out there trying to save the monarchs would start a new movement to save much needed land for pollinators and wildlife. We need to balance out our love for nature with saving all wildlife, birds and pollinators. Not just monarchs, because if there’s no land left. What’s the point of saving monarchs? I’m willing to join in on a movement to force states around our country to protect land for nature and save it from McMansions and strip malls.

ANYONE ELSE?

Enjoy your monarchs. I’m a nervous wreck about mine making it to butterfly, but still loving it!

[…] Tempest in a Teapot […]

I have been planting tropical milkweed for the last 2 years, and enjoying the monarch butterflies in my garden. I live in Palm Beach Florida, and I have been seeing deformed butterflies the last 2 days all coming from the same plant. It’s April now and I’m not sure what to do, I’ve been reading about oe and think this is what’s going on here.

Best to destroy the plant if you have concerns.

Tropical milkweed has been my only option since I started my pollinator garden in late fall. I already had many nectar plants in my yard (I have about 50 varieties of flowering plants in my yard including some that pollinators particularly love like fire bush and honeysuckle. So my yard was already full of monarchs and other butterflies. But they weren’t breeding here. I scoured this whole region for native milkweed and discovered what everyone has been talking about – the commercial nursery industry isn’t ready for the recent increase in demand for milkweed. I just started gardening for the first time in my life 1.5 yrs ago when I moved to SW FL. So I’m not ready to take on plants that are hard to grow like FL native milkweed. I also think it’s counter-productive to plant milkweed that the cats don’t like to eat like butterfly milkweed. I need something that’s easy to grow, a preferred food source, and most of all – available! So I bought tropical milkweed just in time to catch the last of the Monarchs before they continued even further south. Since they laid their eggs so late in the season (late Nov-early Dec), I sure wasn’t going to cut back what I just bought and the Monarchs laid eggs on. So instead, I kept them in pots and when the Monarchs had left, I brought them inside my pool screen where they’re safe from predators and can be moved close to the house where it will be warm enough even during cold nights (we had no freezes here this winter, lowest temp was 39F for a few hours a couple of nights). Result was 7 of those eggs hatched, they had plenty to eat on the 7 milkweed plants I have left (1 died for unknown reason), and 2 of them are now at what looks like their last stage and about to wander off somewhere inside the big lanai enclosure to find a safe place to form a chrysalis. I don’t feel guilty about using tropical milkweed because of the success I’ve had so far. I hope to be able to get to the point where I have to decide whether to bring some nectar plants inside the screen or catch and release the Monarchs after they come of of chyrsalis. The screened enclosure is big enough for them (800+sf, 15+ft high) and safer than outside of it, but not their natural state. So I’m counting on my intuitive relationship with animals to guide me on the right course of action for them.

I live in southwest Florida also. I found a nursery that carries giant Milkweed and the cats are healthier and bigger and the host plant substance multiple cats without eating every leaf. They also seem to go in to chrysalises faster and eclose faster. It grows like a tree and is easy to reproduce with cuttings. And does not seem to have a lot of alphared.

Tropical milkweed is very high in the kind of protective cardenolides that monarchs absorb well — that help monarchs to deal with OE, as well as reducing bird predation.

It’s funny that no one seems to know that.

The best thing for monarchs is more habitat. Acres of tropical milkweed would be a godsend for them, instead of acres of crops, grass, WalMarts, and McMansions.

Yes the milkweed is higher in cardeliones which (while not proved totally yet) seems to be the reason for increase protection against OE. This might seem like a good thing at first glance but the actually problem is a lot more complex. This is because monarchs have adapted to seek out tropical milkweed when they are infected because of the anit-parasitism properties it has. This means that tropical milkweed attracts infected monarchs with can infect the unifected larva on the plant. It also allows a higher percentage of infected monarchs to reach adult hood. The adult monarchs who survive will go on to infect young larva. And here we have the problem. It would be great if tropical milkweed was able to cure the butterflies but all it can do is increase the chances of survival for infected monarchs offspring. Overall tropical milkweed promotes the spread of OE.

Also cardenolides are found in all milkweed and the high amount in milkweed alone tropical actually causes a significant decrease in monarch butterflies lifespan (for the uninfected ones)

So happy I found this article. I was getting worried about planting this milkweed in my yard. I’m a first time home buyer and want to do my part in helping the monarch. Now I know to just cut it back since I live in east Texas. I did have 12 caterpillars but they all started to die. So I need help in what did I do wrong for so many to die.

That is so sad. It is sometimes hard to know, but a couple things come to mind:

Possible pesticide poisoning. One has to be careful where one buys milkweed. Even small levels of so-called organic pesticide is harmful.

Tachinid flies. They are terrible, laying their eggs either on the milkweed for the caterpillars to ingest – or laying their eggs directly on the cat. Either way, the larva eats the caterpillars from the inside, eventually killing them.

I recommend you research the symptoms they are exhibiting. I will say that I have learned to grow the milkweed from seeds, and also keep everything in enclosures so the flies can’t get in.

I wish you luck!

I plant tropical milkweed here in México. I must cut It and burn the plants after they pass through in november and again in march. The monarch has food when passing through. When the plant grows again the monarchs that stay here all year can Lay their eggs and grow to adults without infection.

I maintain that if the choice is tropical milkweed or no milkweed it is better to have tropical milkweed than none at all. If there is no milkweed there will be no Monarchs–end of story. I am a Horticulturist and am experienced at growing plants, and I have tried growing five species of native milkweed with no success. I have tried MANY times! There is nothing I would like better than to grow native milkweed, but I can’t.

I live in a part of SWFL with year round populations sandwiched between two exceptionally large preserves and parks. My Monarch population (in my own Harwood Canopy) had plummeted until I got rid of this nuisance weed. Cutting it wasn’t helping. Unfortunately, Giant and Tropical Milkweed has become the norm here due to lack of knowledge. Our Monarchs are not holding up. I planted natives and my population began to recover after 3 YEARS. So, I would beg to differ that these non-native just need a trim. Who is trimming the plants that end up in our parks and swamps? If we want habit, we need to part of the solution to adding the natives back vs justifying the invasives.