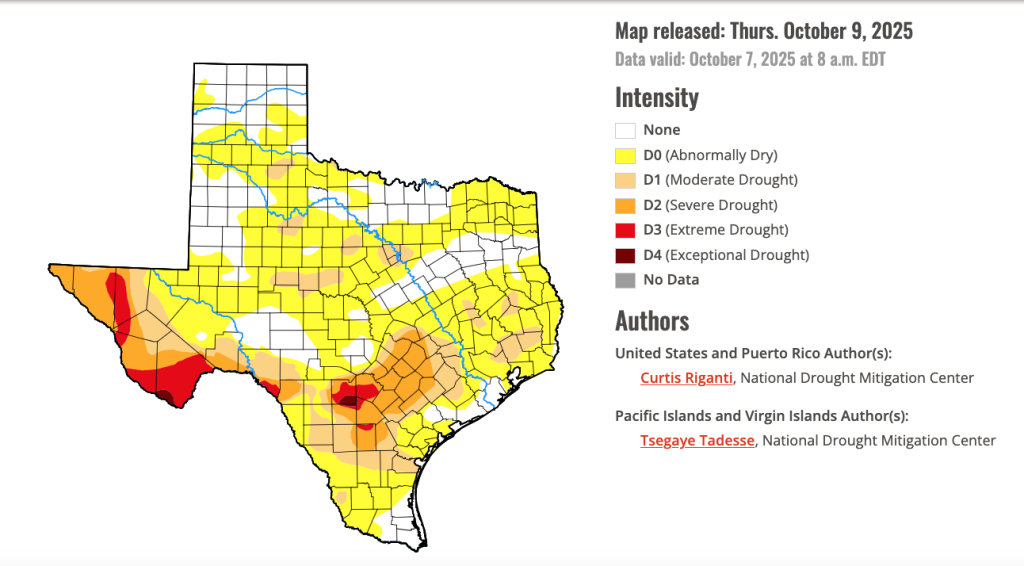

High temperatures appear to have stymied the monarch butterfly migration in the Texas Funnel this year. The area includes the Texas Hill Country and usually enjoys peak monarch migration season October 10 – 22.

Not this year.

Not this year.

“Still no monarchs,” said longtime monarch butterfly tagger and docent of the Grapevine Butterfly Flutterby Festival Jenny Singleton, who’s been tagging monarchs at her ranch in Hext, Texas, for decades. “We need a cold front so bad–but it doesn’t look to be in forecast.”

At our ranch on the Llano River near Mason, Texas, only four monarch butterflies were spotted over four days last weekend. We’ve been tagging roosts there for 20-plus years, and enjoying group tagging outings for my birthday on October 13. For the first time in two decades, the monarchs stood up my birthday bash as no-shows. Several eggs and a single monarch caterpillar were present on the Swamp milkweed dotting the riverbanks, however.

Scientists and monarch aficionados cite the high temperatures for the delayed–or abandoned?– move south by the iconic insect. A recently studied phenomenon of “migratory dropout,” as butterfly and migration studies scientist Andy Davis calls it, appears to be playing a huge role in the absence of monarchs in an area where they historically show up in large numbers this time of year.

The study, published in August and titled “The impact of temperature on the reproductive development, body condition and mortality of autumn migrating monarch butterflies in the laboratory,” was led by a research team from the University of Central Florida.

It demonstrated that monarchs raised in controlled laboratory settings with higher temperatures moved from a nonreproductive state known as diapause into a reproductive phase. IN nature, the insects either migrate to Mexico OR reproduce–they don’t have the energetic capacity to do both. When exposed to the high heat, female monarchs dropped their eggs on the bottom of cages despite the absence of milkweed, the only plant on which they lay eggs. In addition to inspiring egg laying in females, the heat also degraded the overall health of male monarchs, making them less hearty for surviving the winter in Mexico.

A roost of 5,000 or more monarchs was spotted in the West Texas town of Bronte this week by D.Andre Green’s research team.–Photo by D. Andre Green

“Perhaps the most significant threat to monarchs is climate change,” the authors determined, adding that high temperatures during migration season “significantly alter monarch physiology and fitness and provide a mechanism by which climate change could facilitate migratory failure, winter-breeding and overwintering mortality.”

The researchers also said their data was consistent with the supposition that “the North American monarch may eventually transition to partial migration and winter-breeding as the climate continues to warm.”

D. Andre Green, Ecology and Evolutionary Biologist at the University of Michigan, happened to also be in the area last weekend with a team doing research on monarchs and queen butterflies. Green has been experimenting with tracking insects through radio technology for the last few years. Last weekend, despite the void of monarchs in the Texas Hill Country, he witnessed a large roost in Bronte, a West Texas cattle ranching community about 100 miles northwest of the Texas Funnel. He estimated it at 5,000 monarchs.

D. Andre Green tags monarchs on the Llano River on October 12, 2022. –Photo by Monika Maeckle

“It’s been really, really wild,” said Green by phone, driving back to San Antonio to catch a flight north. “They just haven’t come east. They’re to the west. I’ve never seen a roost that size.”

Green speculated that it’s possible that winds and cooler temperatures drew the insects to the west, which lays outside the persistent heat dome that has dogged the Texas Hill Country this fall.

Regarding the recent study, Green said it reminded him of what happened in California several years ago when the monarch population crashed dramatically but then recovered the following year. Many observers theorized that local winter breeding butterflies restored the population the following season. The monarchs’ seasonal recovery demonstrated a capacity for “partial migration.”

“Over the longterm, if there were conditions for populations to remain resident, that would become the norm–some will migrate and some won’t…That may be what’s happening now,” he said.

Texas has experienced a historically hot and long summer, with September seeing a majority of days in the 90s. Even in mid October, temperatures are hitting 90 and hovering in the high 80s. Some of that is attributable to a “heat dome” that has been hovering over pockets of the state. But much of it seems to be part of the general trend of warming weather.

Interestingly, monarch populations have been healthy prior to this end game of migration. Reports from the Midwest and further north have suggested robust reproduction.

In a post on the D-PLEX list, an email list for those following monarch butterfly news and operated by the University of Kansas at Lawrence, Chip Taylor, founder of Monarch Watch, said that this year was the latest migration he has ever witnessed–and he has been following monarchs since 1993.

Want to learn more about the natural history of the monarch butterfly migration? Check out the book!

“Generally, the conditions should favor movement into Oklahoma and Texas unless the temperatures get back into the high 80s,” Taylor wrote on October 4. “Winds will favor westward movement of monarchs in the southeast for much of the week, but movement could be slowed by high temperatures in the afternoons.”

When interviewed for this article this week, Taylor mentioned that he recently witnessed roosts in Kansas.

“Roosts in October in Kansas are unheard of, crazy. I’ve never heard of that before. Roosts are always in the middle of September, not October,” he said, adding that since 1975 temperatures have increased 1.2 degrees per decade. “That’s crazy. It’s really disruptive biologically.”

Whether the monarchs are simply late, deterred, or dropping out of the migration and becoming reproductive remains to be seen.

TOP PHOTO: Monarch butterfly on the Museum Reach in San Antonio, 2022. –Photo by Monika Maeckle

Related articles

- Butterfly Bonanza on the Llano River this weekend–everything buy monarchs

- Monarch butterflies hearing our way as annual fall migration takes flight

- Mother Nature asserts herself with historic flooding in Texas Hill Country

- Monarch butterfly numbers vault 99% over last year’s historic low, California population teetering

- Commercial butterfly breeders brace for devastating hit as monarch ESA listing looms

- Monarch butterflies listed as “threatened” under the Endangered Species Act

- A tense online debate: raising monarch butterflies at home

- New study: monarch migration at risk, monarch butterflies are not

- USFWS rules monarch butterflies worthy of protection, but they don’t have resources to protect it

- As ESA listing looms, new study challenges dogmatic narrative that monarchs are in decline,

- “Weird” weather has scientists concerned about this year’s monarch butterfly migration.

Prolonged southerly winds in Kansas/Oklahoma/West Texas since at least Sept. 24 (today is Oct. 15) have delayed the southward progress of the fall migrants this year, not high temps. But the winds are forecast to shift to northerly directions this weekend and then large numbers of the fall migrants will enter southern Texas and northern Mexico.

So far, I am unaware of any substantial field observation or video evidence that alot of fall migrants in Texas this year are dropping out of migration, becoming reproductive and laying eggs. I doubt that is happening and expect there will be a substantially larger overwintering population in Mexico this winter compared to last year.