As Monarch butterflies finished their tardy, impressive sweep through Texas in early November demonstrating a 2014 population rebound, those in the Monarch community debated the wisdom of listing the iconic migrating butterfly as “threatened” under the Endangered Species Act (ESA).

In late August, the Xerces Society, Center for Food Safety, Center for Biological Diversity and Dr. Lincoln Brower submitted this petition to the Secretary of the Interior requesting the Monarch butterfly be listed as “threatened” under the ESA.

This year’s seemingly healthy population, predicted by experts to be two, perhaps three times as large as last year’s record low, is a welcome turnaround from the post-2010 decline associated with the prolonged Texas drought and other challenges to the migration. The rebound has created a bit of a disconnect, arriving the same year as the petition to consider the iconic migrants’ threatened status.

The reasons for the general decline of Monarchs are well documented: genetically modified and herbicide tolerant crops, continued urbanization and habitat destruction along the migratory path, illegal logging in Mexico, climate change, and pesticide use. The ecosystem that supports the Monarch butterfly migration–and pollinator habitat in general–is tattered. Dr. Chip Taylor stated it well in a recent blog post: “Monarchs clearly aren’t endangered. As this discussion proceeds, we need to make it clear in all communications that it’s about the migration and not the species per se.”

Agreed.

So, is petitioning the federal government to list our favorite butterfly as “threatened” the best way to accomplish that goal? After giving it much thought, I think not.

Threatened status might motivate large corporations and government agencies to be more considerate of Monarchs and other pollinators, but for private citizens with no government or scientific affiliation, such status could be counter productive.

Not in your backyard: if ESA threatened status is applied to Monarchs, each household will be allowed to raise only 10 Monarchs per year. Photo by Monika Maeckle

As one who enjoys Monarchs visiting my urban garden eight months of the year and roosting along the Llano River in the fall, I take particular issue with the federal government telling me what I can do with my land.

Milkweed and nectar plants fill my San Antonio pollinator gardens. We’ve also undertaken a riparian restoration in the Texas Hill Country where Monarchs roost each year, an effort that includes planting native milkweeds and other nectar plants along our riverbanks along the Llano River.

In the course of any given year, I raise several hundred butterflies, not just Monarchs, for fun, joy, and to give as gifts. My goal is to inspire appreciation and understanding of our outdoor world and reinforce the majesty of nature in a small, everyday way.

According to the 159-page petition’s final line, if “threatened” status is approved, such activities would be a crime. People like me and you will be allowed to raise “fewer than ten Monarchs per year by any individual, household or educational entity”–unless that activity is “overseen by a scientist, conservation organization, or other entity dedicated to the conservation of the species.”

This seems to strike at the very heart of what has made the Monarch butterfly so iconic and widely embraced–the crowdsourcing of understanding its migration and the groundswell of interest in conserving it.

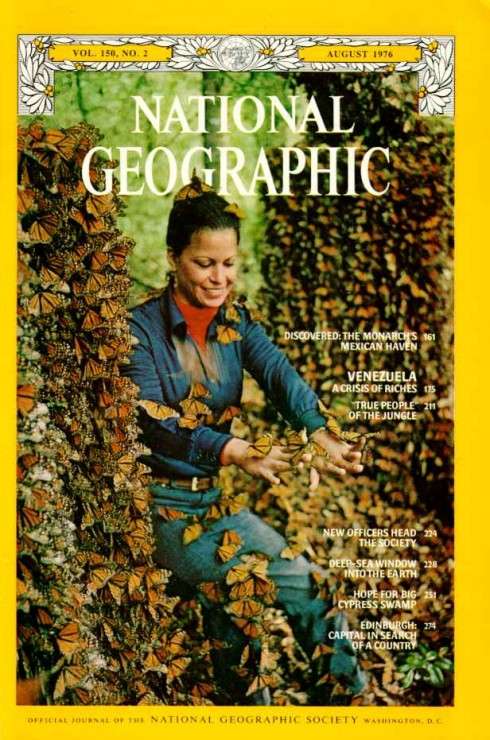

Citizen scientists and individuals like Catalina Trail were instrumental in the discovery of the Monarch roosting spots in 1976. File photo.

Let’s not forget that regular folks like us helped piece together the puzzle of the Monarch migration back in 1976 through Dr. Fred Urquhart’s monitoring project and the intrepid explorations of individuals like Catalina Trail, whose “discovery” of the roosting sites brought their existence to the attention of the world. Making lawbreakers of regular folks for participating and reserving that privilege only for scientists would do more harm than good.

If milkweed becomes part of critical habitat as defined by the ESA under this petition, that would mean destroying milkweed–or getting caught destroying it–would become a crime punishable by fines or mitigation. Civil penalties can come to $25,000 per ESA violation and criminal fines up to $100,000 per violation, and/or imprisonment for up to one year.

Many landowners will simply not plant milkweed or will do away with it entirely just to avoid problems. In some parts of the universe, this is known as Shoot, Shovel and Shut-up, the “practice of killing and burying evidence of any plants or animals that might be threatened or endangered.”

We have seen this attitude first hand in Texas. Ranchers have been known to destroy first growth Ashe Juniper to preserve grass lands and conserve water to avoid ramifications of disturbing the preferred habitat of the endangered Golden-cheeked warbler.

Also, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is cited as the enforcement agent for these rules– but how likely is it that agency personnel will have the bandwidth to do so? If enforcement is not practical, what is the point of the rule?

The petitioners take special issue with the commercial butterfly breeding industry, which supplies eggs, caterpillars, chrysalises and live butterflies for schools, nature exhibits, conservation activities and events. The petition specifically details how conservation education activities like the rearing of Monarchs in school classrooms or at nature centers will be immune to regulation, “provided that the Monarchs are not provided by commercial suppliers.”

That means if a teacher in a classroom or home school situation in New York City wants to teach metamorphosis to fifth graders using Monarch butterflies, she can only do that with butterflies personally harvested in the Big Apple. The best intentions often lead to unintended consequences, and that is what I fear in this instance.

“If only wild caterpillars can be collected and brought into the classroom, we will run the risk of excluding urban children…. precisely what we don’t want,” Dr. David Wagner, author of the guide to Caterpillars of Eastern North America, Dr. Felix Sperling of the University of Alberta and Dr. Bruce Walsh, of the University of Arizona, co-wrote in a 2010 article in the News of the Lepidopterist’s Society.

Again, this seems like a case where federal regulation will do more harm than good since the children that most benefit from the tactile experience of raising butterflies are often those living in urban settings with limited access to nature.

Limiting access to butterflies in the classroom to those found only in the wild will severely restrict access to Monarchs by urban children (who most need it), some scientists say. Photo by Tracy Idell Hamilton

One of the most contentious issues in the petition is a claim on page 74 that “millions” of Monarch butterflies are released into the environment by commercial butterfly breeders each year.

The claim appears greatly exaggerated to the International Butterfly Breeders Association (IBBA), which challenged the number in a press release headlined, “Number of Monarch Butterflies Released Annually Closer to 32,000 than ‘millions and millions’ as Claimed by Endangered Species Act Petitioners.” [DISCLOSURE: I serve on the board of the International Butterfly Breeders Association but do not raise butterflies commercially. I also am a member of the Xerces Society and have hosted both Dr. Chip Taylor and Dr. Lincoln Brower at our ranch.]

The IBBA challenged the basis for such a claim, noting that the “millions and millions” citation was, in fact, lifted from a single newspaper op-ed piece published eight years ago. The author, Professor Jeffrey Lockwood, University of Wyoming, acknowledged the number was guesswork.

“That such an unverified claim surfaced in a formal petition before the Secretary of the Interior demonstrates a serious failure in documentation at best,” Kathy Marshburn, IBBA president, said in the press release.

Dr. Tracy Villareal, an IBBA board member, oceanographer, and part owner of Big Tree Butterflies butterfly farm in Rockport, Texas, called the claim “misleading and poor scholarship.” Villareal told me by phone that he would grade such secondhand references unacceptable in a graduate student’s dissertation.

“The authors made no attempt to determine the composition of the 11 million–how many of each species, for example. Nor did they attempt to contact the author to determine how he arrived at this number. It took me about four hours from my initial email to Professor Lockwood to find out how it was done.” Read the IBBA’s challenge to the numbers for yourself.

OE spores can be debilitating for Monarch butterflies. Concerns about infecting the wild population with the nasty spore persist, and studies continue. Photo courtesy of MLMP

The petitioners believe that commercial breeders release diseased butterflies into the wild population, potentially damaging it. In particular, the unpronounceable Monarch-centric spore, Ophyrocystis elektroscirrha (OE), poses special concern since it debilitates the butterflies and appears to thrive in conditions where the creatures congregate en masse, are crowded, and/or where milkweeds overwinter, carrying the spores into the next season.

Yet, scientists agree that OE is present in the wild population, too, just as Streptococcus, the nasty sore throat-causing bacteria, is present in the human population. Only when health or conditions are degraded does the disease overtake the butterflies. The science is still uncertain on this. Studies continue.

Like any industry, commercial butterfly breeding attracts good citizens and bad, but it seems highly unlikely that people who gravitated to the challenging task of breeding butterflies for a living would intentionally release damaged goods into nature. That just makes for bad business. Does the industry need better checks and balances on the health of livestock released into nature? Absolutely.

The IBBA, an international organization of 104 breeders, plans to release new counts for the number of butterflies released annually at its conference that begins November 12 in Ft. Lauderdale. The organization also will host a discussion on changing or increasing self-policing practices of its membership to keep livestock as disease-free as possible. As Villareal said in a recent email exchange on the DPLEX list, a listserv frequented by hundreds of folks in the Monarch community, “Working from clean breeders is a critical first step in production. I repeat this for everybody in the back row. CLEAN BREEDERS ARE CRITICAL.”

The ESA petition has created conflict in the small-but-passionate world of butterfly advocates. A far better use of the community’s time and energy could be spent on initiatives and public education campaigns to restore migratory habitat.

It’s already happening in many ways, through government and small-but-significant public- private partnerships.

In June, President Obama issued a presidential memorandum calling for all federal agencies to “substantially expand pollinator habitat on federal lands, and to build on federal efforts with public-private partnerships.” Pollinator Week Proclamations have been declared in 45 states, recognizing the vital services that pollinators provide. The EPA released guidance to help scientists assess the potential risks various pesticides pose to bees, and the USDA announced an $8 million initiative to provide funding to farmers and ranchers who establish new pollinator habitats on agricultural lands as part of its Conservation Reserve Program.

Yes, please. Hardberger Park land bridge would facilitate safe movement of wildlife–including pollinators. Photo via Rivard Report

Here in my hometown, we are working with the leadership of San Antonio’s Hemisfair Area Redevelopment Corporation to include pollinator habitat in their upcoming reimagination of the historic 65-acre downtown park that was home to the city’s 1968 world’s fair. Our local public utility, CPS Energy, recently supported the installation of a pollinator garden right downtown at their headquarters on the San Antonio River Walk. And on our city’s heavily developed northwest quadrant, Hardberger Park has a dedicated butterfly garden. The park conservancy is raising money for a spectacular land bridge that will facilitate safe movement of pollinators and other wildlife.

Let’s focus on individual actions and crafting effective public-private partnerships that raise awareness, plant more milkweed and nectar plants and make rebounds like 2014 common fare–and keep the federal government out of our yards.

NOTE: Have you taken our Milkweed Poll? Please do. Three questions, only takes a minute. GRACIAS! Please do it now, here’s the link.Related posts:

- Migrating Monarchs Stymied by Wind, Storms on Llano River

- Migration Update: Lone Cat on Llano River, Butterfly “Cloud” Spotted in St. Louis

- It Takes a Village to Feed Hungry Monarch Caterpillars

- Desperately Seeking Milkweed: Milkweed Shortage Creates Butterfly Emergency

- Migration Update: Llano River EGGstravaganza

- How to Track the Monarch Butterfly Migration from Your Desk

- Monarch Butterflies Headed our Way in Apparent Rebound Season

- Llano River Ready for “Premigration Migration” of Monarch Butterflies

- Pollinator Power on the San Antonio River Walk

- 2014 Monarch Butterfly Migration: Worst Year in History or Hopeful Rebound?

- How to Raise Monarch Butterflies at Home, Part One

- First Lady Michelle Obama Plants First Ever Pollinator Garden at the White House

- Monarch Butterfly Numbers Plummet: will Migration become Extinct?

- NAFTA Leaders, Monsanto: Let’s Save the Monarch Butterfly Migration

Like what you’re reading? Follow butterfly and native plant news at the Texas Butterfly Ranch. Sign up for email delivery, like us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter, @monikam.

Great column, Monika!

As always, insightful, well-considered and provocative journalism at its best and most useful to the readership. Thanks to you – and your support circle – for a great service to quality of life for all critters, supposedly intelligent or otherwise!

As always, your articles are relevant and thought provoking. Is there an official definition of the word “raise” as it relates to the Endangered Species Act or did I miss it in your article? I’d sure like to see that definition before I take a stand. Thanks!

Great article. I’m all for conservation, but to make it criminal to raise them? That’s ridiculous. I didn’t see any monarch on my milkweed this year, but I only had a few plants. I intend to plant more next year in my suburban Fort Worth back yard. I hope that won’t be against the law 😉

Well thought out article. Lots of good points.

The Monarch Butterfly has no protection. There are no laws to protect them. This is what I was told by my Virginia Department of Agriculture representative. The representative said show me the law, two times he repeated this. If a butterfly farmer ships diseased butterflies into your state, there is no law to prevent this. There is no law which regulates that butterfly farmer who shipped those diseased Monarchs. The butterfly farmer does not get fined. There is new research that migratory Monarchs are genetically different than non migratory ones. Florida Monarchs are different than migratory and non migratory. Yet, the USDA/APHIS still allows butterfly farmers/breeders to ship them across state lines when they are physiologically different species. You know what I would like to know. How has the shipping and release of Monarchs butterflies by butterfly farmers/breeders over a 20 year period affected their migration? Has it weakened them genetically from all the inbreeding? Right now, the California and Mexican overwintering populations have decline to just about 10% of their population. Yet, some people argue that they are not “threatened”. The Monarch has such a large territory. It covers Canada, the U.S., and Mexico. What we have been seeing for the past few years is not enough Monarchs to repopulate Canada and the United States during the breeding season. We need to get that petition signed to label them “threatened” so that more research can be funded and their habitat protected. Monarch butterflies are not cockroaches, they need to be protected.

Well said and thank you for adding to the discussion. As of yesterday, the main monarch overwintering site in the Ellwood Complex (Goleta, CA) had nothing to report. Seems to me the Petition to list the monarch focuses a federal effort to help citizens preserve the migration phenomenon itself. Roundup and other killers do not “go away” on their own.

Chris Lange, the Ellwood complex has many cluster areas. I saw and photographed 1,000 at Ellwood Main on Sunday, Nov. 9 and 4,000 at Ellwood West. Ellwood North and Ellwood Sandpiper likely have thousands too, but I didn’t have time to check them. Overall, the California overwintering population looks like it will be about 30% lower this year than last year, but still at or above the average numbers seen the past 15 years.

I am siding with the scientists on this one. I am not a fan of the “keep the federal government out of my backyard” approach that is so often used to stymie environmental and species protection. A 90% decline in monarch numbers in 20 years is severe enough to warrant threatened species protection. Also, the scientists in their petition to the government make quite clear that a ruling should include and encourage citizen scientist efforts: “Once protection is granted, we ask that the Service recognize the important role that research by

scientists and citizen scientists has played, and will continue to play, in understanding and

conserving the monarch butterfly and its habitat. To this end, we request that the Service

streamline the permitting process, so that scientific and conservation research and citizen science

activities are encouraged rather than deterred by a listing. In addition, we support the special 4(d)

rule that the petitioners requested (on p. 159 of the petition) to exempt certain activities from the

‘take prohibition’ in order to facilitate monarch butterfly research, citizen monitoring, education,

and conservation.”

There hasn’t been a 90% decline. More like 60% The sharp declines in 2012 & 2013 in the upper Midwest were due to natural factors, not man made ones. In 2014 the monarch population bounced back in a big way in the upper Midwest – again due to natural factors. And whereas the petition leads readers to believe monarchs numbers have been devastated in the upper Midwest they were actually this abundant there this past September http://www.learner.org/jnorth/sightings/query_result.html?record_id=1409942868

The 90% decline is in the number of butterflies that made the migration to Mexico. It is real and an accurate number. Other pollinators like honey bees have been in decline as well over the last several years. This is a serious problem. Much of this article is well written, but I regret that some folks are getting so attached to this idea that they are under attack that they miss things like the quote in Mobi Warren’s comment that clearly shows the petitioners not only though of, but tried to welcome conscientious butterfly breeders into the process of recovery.

US honey bee colony numbers are stable. In fact, colony numbers were higher in 2010 than any year since 1999.

http://usda.mannlib.cornell.edu/MannUsda/viewDocumentInfo.do?documentID=1191

Hi All,

I am a farmer and our farming associations are watching this as well. If this petition looks like it is going to pass, Monsanto will have a banner year as every farmer I know will be spraying every stalk of milkweed we can see for miles around so the government cannot control our land because it is now considered butterfly habitat. If you think this is going to help the Monarchs, you are crazy. If it passes or looks like it is going to pass and you want to make some quick money, buy stock in Monsanto as they will have a great year.

Hi Monika,

I wonder if you would consider retracting the IBBA press release and reference to it?

If the press release is accurate, commercial butterfly farmers release 750 monarchs each year, and Monarch Watch releases 31,250.

Obviously, this is not true.

If folks are willing to distort, mislead, and misrepresent, then they should be shunned.

Thank you for posting a correction on the % down. 30% is quite a difference to be off. Why would one post intentional inaccurate #’s ? Here in Humboldt, I have seen an increase in Wild Monarchs going thru my yard. A note to all those who feel breeders release oe monarchs? Where did you get your facts from?

Mona Miller raises some very good points about breeders and their impact on Monarch Butterflies. The Spring 2014 issue (Volume 22: no. 1) of American Butterflies (published by the North American Butterfly Association) has a lengthy column on the butterfly house industry and the genetic and other dangers involved in large-scale breeding. This article is posted at http://www.conservationandsociety.org/article.asp?issn=0972-4923;year=2012;volume=10;issue=3;spage=285;epage=303;aulast=Boppr%E9

Aside from Mona’s concerns, I think another issue is that raising butterflies might be superseding much needed lobbying for habitat restoration. We need to work towards conditions that will allow all butterfly species to survive without human intervention.

Any law protecting butterflies should allow for ordinary citizens (not breeders!) to raise them (although I do think enforcement will be difficult in the event it becomes illegal); but really the law, and we citizens, need to go to the root of the problem, which is habitat. I sometimes wonder if the time I spend raising butterflies would be better spent advocating for more wildlife-friendly landscaping in my community.

Mona didn’t identify any known case history examples of adverse impacts of releasing commercially farmed monarchs on the wild monarch populations. Example: releases are most concentrated in the city / suburbs of Los Angeles because of the very high population of humans and the mild year round climate. Yet no study has shown that the monarch cluster sites in Los Angeles such as this one http://www.learner.org/jnorth/sightings/query_result.html?record_id=1415238892 have more diseased monarchs nowadays than they did in the mid-1990’s before the release industry existed.

The article I cited above discusses this in depth. In addition to the danger of pathogens being spread, there is also the issue of the multiple genetic sub-groups in butterfly (including Monarch) species. There is a great deal of local genetic differentiation, such that scientists now speak of “evolutionary significant units” rather than species, since the term “species” is too broad to describe genetic variations in these groups. These sub-groups can have different habitat needs, different behaviors, etc. What happens when you start randomly mixing them is not known. Obviously more work needs to be done, but to have humans unwittingly manipulating and then mixing genetic strains without knowing the outcome seems not constructive to me.

Commercially farmed monarchs don’t harbor pathogens that don’t already exist widely in the wild. So releases can’t spread novel pathogens to the wild. Monarchs in the USA are migratory, hence do not have locally adapted populations. Bruce Walsh, a University of Arizona population geneticist, explains it this way: “by the nature of their long-range migrations, Monarchs have a very unstructured population and therefore little chance for local adaptation. One of the (incorrect) concerns often raised is that releases may introduce deleterious alleles into natural populations. While there is no evidence of this, even if this were true, classic results on migration-selection balance imply that any such alleles are quickly removed from the population with little effect. “

In regards to OE and other pathogens, the column states that “the impact of many pathogens is more acute for insects bred or flown in crowded conditions, or otherwise under stress.”

Re genetics: “There is considerable risk of genetic mixing among those butterflies bred for ceremonial releases (see below), of which the monarch butterfly is a prime example. Monarchs are also used frequently in butterfly houses. It is not widely appreciated that this species is divisible into several subspecies (Brower et al. 2007). Most houses use stock of the North American migratory monarch, which forms a major subpopulation of the nominate subspecies, Danaus plexippus plexippus. South of Mexico, monarch populations are not known to exhibit long-distance migratory behaviour, and most are considered to belong to various distinct subspecies. Accidental release, for example, of Costa Rican monarchs supplied to a butterfly house in eastern Canada could have unknown consequences were they to hybridise with the local migratory population. Recent research has demonstrated that the migratory ability of this butterfly is fine-tuned by a system under direct genetic control (Reppert et al. 2010).

In Costa Rica, the Pacific and Atlantic coast populations of several Morpho species will almost certainly become mixed, due to butterfly farmers who mass-rear M. peleides at a rate of many hundreds per week. The threat this represents is unknown, but it seems likely that mixing has already occurred through exchange of breeding stock. 12 “

The worst case scenario for OE parasite transmission from commercially farmed monarchs to the wild monarchs is Los Angeles, because that’s the geographical region where releases are most concentrated. Yet no researcher has determined that there has been an increase in OE parasite spore levels in the wild monarchs at the Los Angeles monarch cluster sites during the past 20 years during which releases became popular in Los Angeles. With regard to genetics, five separate studies have determined that all USA and Canadian monarchs are genetically indistinguishable from one another. Costa Rican monarchs are genetically different, but Costa Rican monarchs cannot be legally shipped to the USA and Canada for release. If they did accidentally escape and pass on deleterious alleles to the wild Canadian monarchs those alleles would be quickly removed with little effect as Bruce Walsh explained.

Paul,

I will concede that according to the evidence you present, commercial breeding of monarchs may be done safely. A lot of that has to do with how breeders regulate themselves. I am under the impression that the Endangered Species Act was written to disallow this because people don’t always do the right thing.

Although I’m not anti-commercial breeding, I’m also not a supporter of it; it’s about serving human need–and commerce–rather than serving the species. To really serve the species, we need to adjust how we manage our land so that non-human species can survive in the natural way–without human assistance. That way we can eventually leave well enough alone and stop having to interfere with them. In other words, it should be first and foremost about their needs, not ours.

The core of the disagreement here I think is contained within Monica’s admonishment to “keep the federal government out of our yards.” I get it, although I really don’t think the feds are going to come and monitor my butterfly meadow once the law goes through. (And if they did, I think they’d like what they find.) It’s Monica’s blog, and if she’s against the feds and the manner in which they want to help wildlife, that’s her right to say.

However, I’m not convinced that the scientists who work for the government (and I’ve known a few) are clueless about how to help species. It seems counterintuitive to me, and a little disturbing, that advocates for a species would leave it completely to the good will of individuals to help that species survive.

Ruth,

This is a very comprehensive and informative article. Dense, even enjoyable if disturbing reading. Thank you for the link.

Yes, dense. I have not read it word for word; I plan to do so soon. I’m happy you found it helpful.

Ruth, great post. We need everything–local education and appreciation events, school curricula, individual dedication in one’s home and garden space and local public areas…and VERY IMPORTANTLY, spreading the word TODAY to get letters of support to the Secretary of the Interior, UFWS chief and also head of the USFWS branch of listing, Endangered Species Program–deadline November 27. Great letters with multiple signatures of scientists and NGOs have already been sent–we need more!. Again thanks Ruth for your responses.

Chris,

To be honest, I had email contact with one scientist a couple of days ago who does not support the listing for scientific reasons. I did not really understand his reasoning as stated briefly in an email, and thus it didn’t make sense to me. I will try to find out more by reading some documents he sent me.

Thus, if there are indeed good scientific reasons for not listing, they should get a fair hearing. But I don’t feel that commercial interests or philosophical beliefs about government intrusion should be factors that derail listing in this case.

How about BOTH? Raise them AND advocate!!

Yes, of course, both are necessary. But as individuals we don’t all have enough disposable time for multiple projects and need to choose our activities.

[…] fines or mitigation,” Monika Maeckle, a conservationist and self-described butterfly evangelist, explained on her blog at the Texas Butterfly […]

So that’s the case? Quite a retialveon that is.

A Xerces representative told me that their 4(d) rule will allow individuals to raise 10 (August 2014). But, the “FAQs ON THE MONARCH BUTTERFLY ENDANGERED SPECIES ACT PETITION” posted on the Xerces website states that scientists, citizen tagging, and children rearing will be petitioned to continue as part of the petition and does not specify a number: http://www.xerces.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Monarch-ESA-Petition-QA.pdf

“IF LISTED, CAN CHILDREN STILL

RAISE MONARCHS? CAN CITIZEN

MONITORS STILL TAG MONARCHS? CAN

SCIENTISTS STILL DO EXPERIMENTS

WITH MONARCHS? If the monarch is protected,

then children will still be able to raise them in classrooms

and at home, scientists will still be able to conduct research

using monarchs, and citizen monitors will still be able to tag

monarchs. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service will implement

a permitting system to allow these activities to continue in

a manner that supports monarch conservation. Petitioners

have specifically requested that the Service implement a

“4(d) rule,” a special rule under the ESA that would allow

activities that support monarch conservation to continue

so that those beneficial activities will not be considered as

“take” or harm to the monarch population.”

The 4(d) rule posted to the Center for Food Safety website, which is an amendment to the August 2014 petition, says individuals should be allowed to raise 100 (dated March 2015). https://www.centerforfoodsafety.org/files/monarch-esa-petition-4d-rule_61731.pdf

“PETITIONERS HAVE SUGGESTED A 4(D)

RULE THAT WOULD ALLOW HANDLING

OF MONARCHS TO CONTINUE. To facilitate

monarch butterfly conservation, science, citizen monitoring,

and education, the petitioning groups requested that the

Service adopt a 4(d) rule that would allow wild-captured

monarchs and caterpillars to be reared in classrooms and

nature centers and that would allow scientific research,

citizen monitoring, and beneficial household rearing

endeavors to continue without the need for a permit.”

Seriously, people shouldn’t be fighting about how many people will get to raise, we should be more concerned with saving the migration. The key to saving the migration is creating habitat. I would also recommend that the Monarch butterfly be taken off the USDA/APHIS release chart. There are way too many inbred, diseased Monarchs in all stages being shipped by butterfly farmers for rearing, further breeding, and release.

Many of these farmed butterflies carry diseases and are inbred. Farmers claim that their stock is screened by a pathology lab, but that lab does not screen for genetics or screen for all pathogens. Selected stock and species are screened by butterfly farmers, if screen at all, on a random basis; thereby, leaving the possibly of an undetected disease outbreak. The average customer would not be able to determine if their stock had genetic or other diseases. Please create habitat and attract species locally, this will ensure that you will not be adding genetically inbred species or subjecting local species to further diseases. (See — Captive Breeding and Releasing Monarchs — http://www.xerces.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Captive-Breeding-and-Releasing-Monarchs_oct2015.pdf)

Journey North has a good website on “How You Can Help Monarchs.” This page has many good resources: https://www.learner.org/jnorth/tm/monarch/conservation_action_resources.html

This article is still relevant!!

Here we go again!