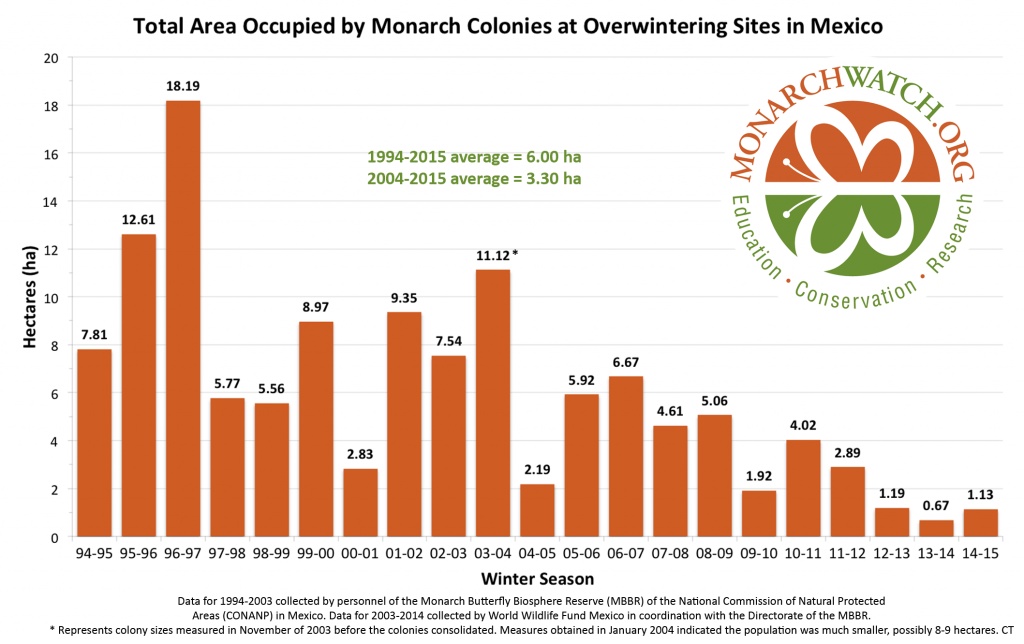

Last week, the Mexican government announced the number of Monarch butterflies counted at the ancestral roosting sites in the oyamel forests of Michoacán, Mexico.

The population grew by almost 70% since last year–from 34 million butterflies occupying 1.65 acres (.67 hectares) in 2014 (the worst year in history) to 56.5 million butterflies occupying 2.79 acres (1.13 hectares) in 2015.

Good news: Monarch butterfly numbers up. Bad news: numbers still dangerously low. Graphic via Monarch Watch

Good news, right?

That depends on where you sit. Dr. Lincoln Brower, perhaps the person on the planet who has studied the Monarch butterfly migration longer than anyone, called the 69% increase “catastrophic” in a phone interview.

“That change is trivial,” said Brower. “We were thinking it would be more than two hectares. What we need is up to five hectares.”

George Kimbrell, senior attorney for the Center for Food Safety, said in a press release posted on that organization’s website that despite the increase, the Monarch population is still “severely jeopardized by milkweed loss in their summer breeding grounds due to increasing herbicide use on genetically engineered crops.”

Kimbrell’s organization, with the Center for Biological Diversity, the Xerces Society and Dr. Brower, filed a petition in August to list the Monarch butterfly as “threatened” under the Endangered Species Act. The petition is currently under review.

If only we could all grow native milkweeds like this Swamp milkweed, Asclepias incarnata, found on the Llano River in the Texas Hill Country. Aphids come with the territory. Photo by Monika Maeckle

“Extremely vulnerable” is how Dr. Chip Taylor, founder of the citizen scientist Monarch tagging organization Monarch Watch, categorized the increase in a January 27 blogpost. While population increase represents improvement, “Winter storms or poor conditions for breeding in the spring and summer could have a severe impact on a population of this size,” wrote Taylor. He added that if we can get through the winter with no major storms “the long-range forecasts suggest that the population has a good chance of increasing again next year.”

So…numbers up slightly, but still dangerously low. Bad news, right?

Well, not entirely.

Thanks to all the angst and attention, awareness of the decline of the Monarch butterfly migration has reached unprecedented heights. And everyone–even the folks at Monsanto– seems to agree on one point: habitat loss, specifically restoration of native milkweeds, must be addressed on a grand scale if we are to keep the migration from becoming a memory.

We couldn’t agree more. This website has documented and addressed the dearth of native milkweed over the years, answering many questions from readers who want to do the right thing. Where to get them? Should one plant seeds or seedlings? What are the best practices for getting native milkweeds to grow?

The problem is that it’s near impossible to find native milkweed plugs locally. The only milkweed plants available in commercial nurseries each spring is Tropical milkweed, Asclepias curassavica, which some scientists have suggested might increase diseases in Monarchs. (I don’t necessarily buy this theory.) To play it safe, best practice suggests cutting Tropical milkweed to the ground in the winter in warmer climates so nasty OE, Ophryocystis elektroscirrha, spores, which infect Monarchs and other milkweed feeding butterflies, can’t collect on old plants and infect migrating Monarch butterflies.

That said, we would all prefer to plant native local species–IF we could find them. Native seeds are relatively available, but getting them to germinate can be tricky. As George Cates, chief seed wrangler at Native American Seed in Junction, Texas, once told me, Texas milkweeds “may not lend themselves to mass seed production.” Personally, I have spent hundreds of dollars and many many hours spreading native milkweed seeds and homemade native milkweed seedballs at our Llano River Ranch. In 10 years, only three–count ’em–Antelope Horns, Asclepias asperula, milkweed plants have taken root.

That brings us to plugs. I’ve tried those, too. One year I finally coaxed some Antelope Horns seed to germinate after following these directions from the experts at Native American Seed, only to have the seedlings die once transplanted.

In response to a survey conducted by the Texas Butterfly Ranch in late 2014, we’re exploring the possibility of growing native Texas milkweed here in San Antonio with a hydroponic partner, Local Sprout. We haven’t figured out all the details, but we’re working on growing Swamp milkweed, Asclepias incarnata, from seeds harvested on the banks of the Llano River.

Meanwhile, we challenge local nurseries and growers to rise to the challenge and make local, native chemical free milkweeds available for the spring migration as well as in the fall.

Related posts:

- MIlkweed Guide for Central and South Texas

- Endangered Species Act Wrong Tool for the Job of Monarch Butterfly Conservation?

- How to Get Native Milkweed Seeds to Germinate

- Monsanto: Absolutely committed to Monarch Butterfly Conservation

- Native American Seed and the Challenges of Persnickety Texas Native Milkweeds

- It Takes a Village to Feed Hungry Monarch Caterpillars

- Desperately Seeking Milkweed: Milkweed Shortage Creates Butterfly Emergency

- Llano River Ready for “Premigration Migration” of Monarch Butterflies

- Pollinator Power on the San Antonio River Walk

- 2014 Monarch Butterfly Migration: Worst Year in History or Hopeful Rebound?

- How to Raise Monarch Butterflies at Home, Part One

- First Lady Michelle Obama Plants First Ever Pollinator Garden at the White House

- Monarch Butterfly Numbers Plummet: will Migration become Extinct?

- NAFTA Leaders, Monsanto: Let’s Save the Monarch Butterfly Migration

Like what you’re reading? Follow butterfly and native plant news at the Texas Butterfly Ranch. Sign up for email delivery, like us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter, @monikam.

We bought some native seeds from Native American and have them chilling in the fridge right now. We’ll let you know if we get any survivors from the batch!

Another great and timely post, Monika! Thanks for doing these! We would love to grow more native milkweed if we could just get it to grow.

Interesting post, Monica. It’s really helpful to see the graph, and I agree with Dr. Brower: it does look ominous still.

As for milkweed, I’m curious about your experience trying to grow it from seed bombs and plugs. We live in Northern Minnesota, and we’ve had absolutely no problem with plugs.

So far we’ve grown Common Milkweed and Swamp Milkweed from plugs. We then disperse the seeds from those plants in our native meadow, and although the rate of germination is small, we always do have some new plants coming up the next summer. Which makes sense, because that’s how nature does it.

In my butterfly garden, there is so much re-seeding going on that last summer I actually had to pull up excess young milkweed plants because I didn’t have space to transplant them all.

I’m wondering if you have native horticulturalists where you live who could help you determine what the issue is that is interfering with your milkweed growth? Milkweed should not be hard to grow–it used to grow like a weed(!).

I have common milkweed seed (native to the US) from my Michigan garden available for anyone who sends me a two stamps. I have at least 50 packets left and need them gone before spring.

i would be very happy to plant milkweed on our acre and on the neighbors too if i could figure out what to plant and where to get it here in tn or online it is very confusing xx

WhatWhat if you do get native milkweed to grow and it’s still alive during the fall migration? Is that a possibility here in South Texas? Should they also be cut down to eliminate the OE? Other than being an expert in plant identification or having the luck of buying a plant with a tag, do you identify the trpoical vs the native just by bloom color? Is the tropical milkweed only the red and yellow combo bloom? Is the one that is just yellow native? I know what antelope horn looks like.

To my knowledge, none of the native milkweed promoting dot orgs has posted photos showing examples of how large patches of common native midwestern milkweeds (viridis, asperula, latifolia, syriaca) were successfully established from seed or plugs in wild settings such as along roadsides, fencelines, crop margins and in pastures. Thus I am left to assume they have no or few wild landscape success stories to share with us. Also, these dot orgs do not favor planting monocultures of milkweeds even though the monarchs would benefit more from large, solid stands of milkweed. Instead, they favor planting a diverse array of wildflowers with just a few milkweeds included here and there.

Thanks for sharing another great report. These days, even small gains bring me hope.