A recent designation of the monarch butterfly as “endangered” by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) had monarch aficionados’ heads spinning last week.

The organization, composed of government agencies and NGOs from around the world, issued a press release July 21 adding the monarch butterfly to its Red List of Threatened Species, citing habitat destruction and climate change.

And yet in May, news broke that the eastern migratory monarch population enjoyed a 35% increase this year over last. In January, conservationists announced that the number of California’s monarchs, which move up and down the Pacific Coast, vaulted more than 12,000% in 2021. Given such robust monarch numbers over the past two years, the IUCN “endangered” designation came as a surprise.

“Can we still tag monarchs?” wondered Drake White, chief docent for San Antonio’s Monarch Butterfly and Pollinator Festival.

White oversees a team of trained docents that conduct one-on-one tagging demos at the celebration that takes flight each October in the nation’s first Monarch Butterfly Champion City, so named by the National Wildlife Federation.

The short answer is YES, we can still tag monarch butterflies.

While the Geneva-based IUCN is considered one of the most comprehensive sources on the conservation status of animals, plants and fungi, it has zero jurisdiction nor governing authority.

“The term ‘endangered’ captures people’s attention, but it doesn’t mean what people think it does,” said Ross Winton, an invertebrate biologist for Texas Parks and Wildlife.

Winton recalled the decision in 2020 by U.S. Fish and Wildlife on listing monarch butterflies as “threatened” under the Endangered Species Act. The federal agency determined the listing was “warranted but precluded” but failed to list them due to a lack of resources to protect them, moving them into the queue behind 161 other species. The issue is expected to be revisited in 2024.

The iconic orange-and-black butterflies are widely known for their unique, multi-generation migration that takes them each spring from their overwintering habitat in the mountains of Mexico through Texas to Canada and back.

San Antonio sits in the so-called Texas Funnel, a migratory pathway that sees large numbers of the insects each year. The Alamo City, like much of Texas, is also home to a fairly stable monarch butterfly population, according to Winton. Texas Parks and Wildlife recently conducted its own statewide monarch butterfly assessment.

“It came back that it’s secure, but that’s using different data sets than IUCN,” Winton said.

Monarch Joint Venture, a monarch butterfly conservation organization, clarified in a statement that the IUCN designation does not provide any protections or regulatory authority like an Endangered Species Act listing in the U.S. would.

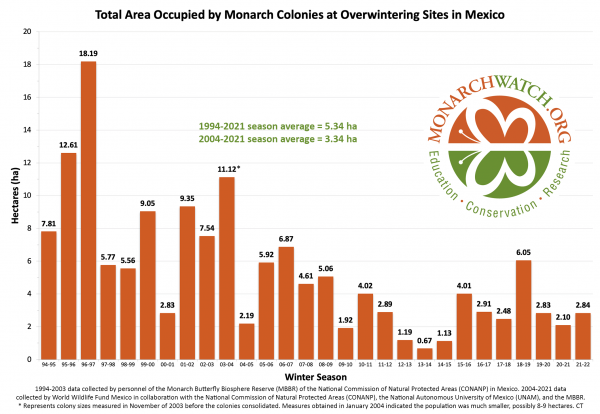

The most recent population counts for migrating monarchs east of the Rockies shows a 35% increase over last year. –Graphic via Monarch Watch

“This is another loud call to action that we need all hands on deck for monarch and pollinator conservation,” said Wendy Caldwell, the organization’s executive director.

Another source of confusion: in their press release, the IUCN referred to the “eastern migratory monarch butterfly” as a “subspecies of the monarch butterfly Danaus plexippus.”

Scientists have debated if migrating and nonmigrating monarchs and those that live east or west of the Rocky Mountains have innately different DNA for years. A recent study, titled “Are eastern and western monarch butterflies distinct populations?” seems to have put that argument to rest.

As the study’s lead author Micah Freedman told the MonarchScience blog, “The evidence pretty strongly suggests that they (western monarchs) are genetically indistinguishable from eastern monarchs, and the (relatively minor) differences that do exist between wild eastern and western monarchs are likely environmentally determined.”

Andy Davis, author of the MonarchScience blog and editor of the Migration Studies Journal, went so far as to suggest that the IUCN listing was a PR stunt meant to fuel the dogma of doom surrounding monarchs. “The public ‘narrative’ around the monarch…is becoming more and more divorced from reality,” said Davis in a recent post about the listing.

In his own recent study, Davis makes compelling science-based arguments that the monarch butterfly itself is not endangered.

Drawing on butterfly survey data pulled from 130,000 observations over 25 years in two countries, he concludes that there’s been “no overall decline in numbers of monarchs seen in the past 25 years, going back to the mid 1990s. In fact, there was an overall positive trend of 1.3% per year. Over 25 years, that’s about a 30% increase!”

“It’s hard to sort it out,” said Cathy Downs, referring to the mixed messages.

Downs propagates milkweed, the monarch butterfly’s host plant, in her yard in Comfort in the Texas Hill Country. She also works as a monarch conservation specialist for Monarch Watch, a citizen science initiative based at the University of Kansas at Lawrence that tracks the monarchs’ migration each fall by tagging the creatures.

“I’m glad they issued the statement and brought monarch conservation back to the forefront,” she said.

The endangered designation by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature carries no authority over the tagging of monarch butterflies as an Endangered Species Act listing in the U.S. would. —Photo by Monika Maeckle

When the Endangered Species Act listing was being debated, those who tag monarch butterflies raised concerns that they would no longer be able to participate in the initiative to track the migrating insects via tiny stickers placed strategically on their wings, as the listing would likely prohibit such interactions with a protected species.

But that’s not a worry here, said Chip Taylor, founder of Monarch Watch.

“The IUCN has absolutely no jurisdiction in the United States,” said Taylor. “It’s a wake-up call.”

Related posts:

- Eastern monarch population up 35% this year, but still much work to do

- Dejavu: is 2022’s dry spring setting the stage for another Texas drought like 2011?

- Three monarch butterflies tagged in honor of those who died recovered in Mexico

- They’re here! Drought conditions greet monarch butterflies as they arrive in Texas

- Massive arrivals of monarch butterflies in the Texas Hill Country signal 2021 migration is on

- Courtship flights, late departures define recent visit to Piedra HErrada sanctuary

- Late, robust monarch butterfly migration evokes cautious optimism

Like what you’re reading? Don’t miss a single post from the Texas Butterfly Ranch. Sign up for email delivery, like us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter, @monikam or Instagram.

Thank you for this! I’ve been perturbed ever since the news came out and even had to correct Tallamy’s Home Grown National Park to put up something that this had no bearing on policy in the US. It’s been frustrating to see people latch on without any nuance or detailed info.

You’re welcome! Thanks for reading and writing. —MM

This is all click-bait. US Fish & Wildlife which determines US listings has a request to list them as threatened. They postponed decision until 2024. This group from Switzerland wanted to list Tigers as endangered, but what “news provider” in the US would pick up that story? Hijack the Monarchs and add them to the list and presto – the story of the year, and lots of clicks on their “DONATE NOW” button. Magnificent scam of the year.

Read, people, and understand.

Great article, Monika! I wish we could join the study and tag in the Spring area! We enjoy bringing the caterpillars in and observing them every year. It never gets old!! I’m not seeing many at our place in Western NC yet, however, there is a ton of milkweed around here and along the Blueridge Parkway! Several native varieties abound!!!

I see Monarchs frequently in the San Francisco Bay area in California.

I too noticed the article about the endangered species listing and chose to ignore it. I think Steve is correct. It is Click Bait and a scam…..

.to enhance revenue!

Thank you Monika for your article and analysis!

I’m not a scientist and have only my own powers of observation re. the numbers of monarchs that pass through Northeastern Pennsylvania, but they are virtually extinct here. Whereas there used to be so many passing through that no one bothered to count them, for the past ten or more years, I have not observed more than one or two per migratory season.

Fall Migrant Monarchs were this abundant on the farmlands of south-central Minnesota 10 months ago:

I saw the designation as well, and wondered what power they have. It is true that many citizen scientists have been helping the cause, and we are seeing increases in the numbers from a variety of efforts.

I do wonder that the overwintering habitat in Mexico is not defended adequately from loggers – and I am wondering if this international designation will assist Mexico with their conservation efforts? Would be nice to think so!

The Monarch’s use to be plentiful here in Deep South Texas . I have seen a big decline in the migration in the last 5 years because of habitat destruction.

We are one of the major migration routes on there way to the Mountains in Mexico they come here to rest a refuel. I’m in the process of getting our city on board to let the empty lot grow in August until the end of November and give them back the habit so they can make the rest of their journey.