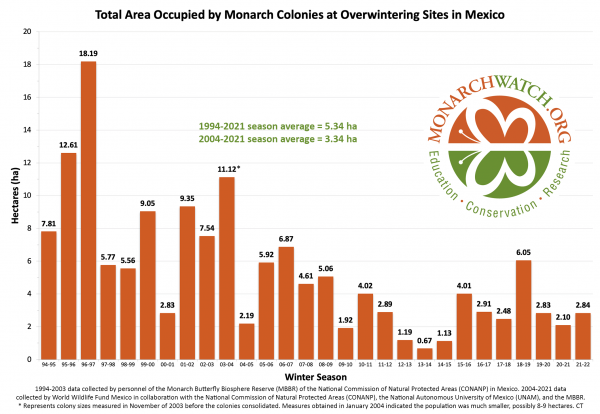

The number of monarch butterflies overwintering in Mexico increased 35% last winter, the World Wildlife Fund announced this week.

In December 2021, the most recent season and the month in which monarch population surveys are typically conducted, the butterflies occupied 2.835 hectares/7.02 acres of high altitude pine and fir forest in the mountains west of Mexico City where they spend their winters. In December 2020, they occupied 2.10 hectares/5.19 acres.

Since it’s impossible to count each butterfly, population counts are determined by conducting a survey that measures the number of hectares/acres of forest the monarchs occupy each winter in their overwintering roosts. This provides an indicator of their population status.

Jorge Rickards, general director of World Wildlife Fund México, said that the increase in the eastern population that migrates through the U.S. to Canada and back to Mexico each year was good news, but noted that butterfly numbers were still well below those recorded three years ago. Read the WWF press release here.

Monarchs cluster on pecan limbs along the Llano River, October 2022. Photo by Lee Marlowe

“The increase in monarch butterflies is good news and indicates that we should continue working to maintain and reinforce conservation measures by Mexico, the United States, and Canada,” Rickards said in a statement.

Monarch butterfly conservationists expressed cautious optimism at the news.

“A modest increase from last year’s population to 2.84 hectares is still welcomed news!” Wendy Caldwell, executive director of monarch butterfly conservation organization Monarch Joint Venture, said in a statement.

“I was wrong, really, really wrong, and I’m happy about it,” wrote Chip Taylor of Monarch Watch, the community science organization that taps volunteers to tag and track the butterflies each fall, in a recent blogpost on the organization’s website.

In January, Taylor had predicted a significant decline in the population, based on drought in the Midwest, extreme heat in the breeding grounds, and a later-than-average 2021 migration. “In the future, I will be using a different set of measures, ones that appear to be better at predicting how the population develops each year,” he wrote.

Scott Hoffman Black, executive director of the Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation, was quoted on that organization’s website saying “we still have a long way to go.”

“This is great news and gives us some breathing room as we work to recover monarch numbers,” Hoffman said. “But there is still a long way to go to ensure that my grandchildren will be able to see monarchs every summer.”

The 2022 population number is well below the benchmark set by the U.S., Mexico and Canada to maintain a healthy migration. The three countries agreed in 2016 that maintaining an average overwintering population of 6 hectares would be required to sustain the migration.

As monarch scientist Karen Oberhauser pointed out on the Journey North website, the 6 hectares average would give monarchs a reasonable buffer against declines that often occur from one year to the next.

“Monarch numbers have declined by over 50% from one year to the next several times during the years that they have been monitored. If that happened after a year with already low numbers, the population might not be able to recover. Thus, while this increase is hopeful, monarchs are still not ‘out of the woods,’” Oberhauser wrote.

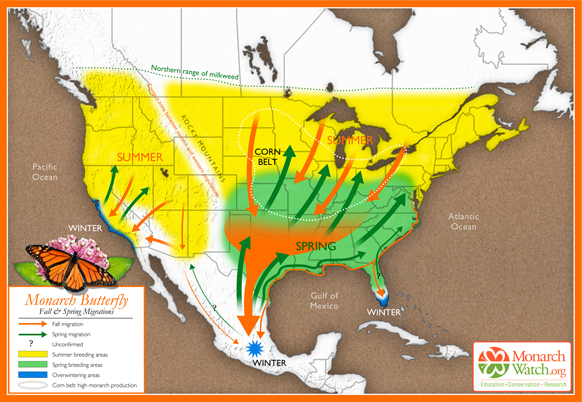

The World Wildlife Fund attributed the ongoing decline of monarch butterflies to a lack of milkweed, the butterflies’ host plant and the only plant on which they will lay eggs; illegal logging in Mexico; and climate change.

The eastern monarch population migrates from Mexico, through Texas and the Midwest to Canada and back; the western monarch population moves up and down the California coast.

The news followed a dramatic recovery for the western monarch butterfly population.

In January, conservationists reported the western population, which migrates along the California coast and numbered about 2,000 butterflies in 2020, jumped to almost 250,000 butterflies in 2021–an increase of more than 12,000 percent.

The 2022 eastern migratory season has gotten off to rough start in the Texas Funnel, the migratory corridor through which eastern migrating monarchs must pass on their way to and from Mexico on their multi generational migration.

Extreme heat and an ongoing drought quashed the butterflies ability to lay eggs in South Texas earlier this spring, typically their first reproductive stop to a new season. Milkweed and other wildflowers were largely absent due to a lack of moisture.

TOP PHOTO: Monarch butterflies in Cerro Pelón Mexico. –File photo

Related posts:

- Dejavu: is 2022’s dry spring setting the stage for another Texas drought like 2011?

- Three monarch butterflies tagged in honor of those who died recovered in Mexico

- They’re here! Drought conditions greet monarch butterflies as they arrive in Texas

- Massive arrivals of monarch butterflies in the Texas Hill Country signal 2021 migration is on

- Courtship flights, late departures define recent visit to Piedra HErrada sanctuary

- Late, robust monarch butterfly migration evokes cautious optimism

- Monarch Butterfly and Pollinator Festival takes flight from new roost at Confluence Park

- Mostly native butterfly garden outperforms lawn every time

- A year in the life of an urban butterfly garden

- Downtown River walk plot converts to pollinator garden, creature haven

Like what you’re reading? Don’t miss a single post from the Texas Butterfly Ranch. Sign up for email delivery, like us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter, @monikam or Instagram.

On the one hand the conservation orgs have been telling us: “we have not come close to replacing the milkweed habitat that was lost early in the 21st century” but they havn’t been telling us whether the amount of new milkweed being planted each year is reversing the situation? In other words, is far more milkweed still being lost from the landscape each year than is replaced through planting?